The History Buff's Guide to World War II (25 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

In the end the Japanese did achieve most of their objectives, linking with garrisons in Indochina on December 11, 1944, but a withered supply line halted any further progress, and U.S. victories in the Pacific made most of the gains irrelevant. Tokyo had spent itself in Asia, and Chiang’s Nationalists were routed, but another group benefited greatly from Ichi-Go. By watching the two main rivals fight to the death, Mao Zedong’s Communists suddenly became major contenders in the fight for China.

Per usual, the Chinese did not have the weapons to stage effective resistance during Ichi-Go. One regiment fought using two rather vintage artillery pieces. The guns previously belonged to the French army and had been used in the First World War.

7

. SAIPAN (JUNE 15–JULY 9, 1944)

Saipan was the home base of the Imperial Central Pacific Fleet and the headquarters of Vice Adm. Nagumo Chuichi, the man who directed the air assault on P

EARL

H

ARBOR

. The island was also within heavy bomber range of Japan. In the summer of 1944 the United States was determined to take the island, and the Japanese were just as determined to hold it.

The attackers had advantages. Japanese air cover was almost nonexistent. U.S. submarines were sinking transport after transport of soldiers and supplies heading for the area. American marines and soldiers outnumbered the defenders almost three to one. The Japanese also had to protect more than thirty thousand civilians on the island. But Saipan—fourteen miles long and five miles wide—was littered with swamps, ravines, high peaks, and thickets of jungle, interspersed with caves ideal for defensive positions. Guarding their few beaches were reefs of jagged coral.

Though landing more than twenty thousand troops on the first day, the Americans were under almost constant fire. Units got lost. Fragile battle lines broke, reformed, and broke again. Torrid accusations of incompetence flew back and forth between marine and army commanders. As the battle entered its third week (it was supposed to last only three days), the Japanese launched the largest banzai charge of the war. More than three thousand men, some only armed with grenades, nearly liquidated two American battalions.

Trapped on the island, Nagumo committed suicide, as did several thousand of his men. Of the Japanese civilians, some twenty-two thousand jumped or were forced off the seaside cliffs on the west and north sides of the island. Others killed themselves with grenades or simply walked into the sea to drown. U.S. patrol boats struggled to move through the floating corpses.

102

In the battle of Saipan, U.S. Marines suffered four thousand casualties in the first two days of fighting.

Back in Japan, the defeat meant the end of Prime Minister Tojo Hideki, who resigned along with his entire cabinet, as did the minister of the navy and the chief of navy general staff. In light of the impending attacks from B-29 bombers, Emperor Hirohito inquired if there was a way to quickly and favorably terminate the war.

Nearby Tinian and Guam islands were taken soon after Saipan fell. The three islands served as a hub for B-29 operations, and Tinian was the take-off point for both the Enola Gay and Bock’s Car on their atomic missions.

8

. LEYTE GULF, THE PHILIPPINES (OCTOBER 23–26, 1944)

The largest naval engagement of the war began over a fight for land. In October 1944 Gen. Douglas MacArthur fulfilled his promise to return to the Philippines, invading the island of Leyte with 175,000 men under the protection of two U.S. fleets. In response, Adm. T

OYODA

S

OEMU

sent nearly every surface vessel left in the Imperial Navy, more than seventy warships, to crush MacArthur and the U.S. Sixth Army on the Leyte beachhead.

Though complicated, Toyoda’s plan almost worked, primarily because Allied

INTELLIGENCE

had not deciphered the code variation used to coordinate the attack. Using a diversionary force of four carriers, the Japanese lured the U.S. Third Fleet, assigned to protect the landings, northward and hundreds of miles away from Leyte. While the Third Fleet feasted on this sacrificial lamb, the bulk of the Imperial forces descended upon MacArthur and the remaining Seventh Fleet, curling around the island from the north and south.

The southern claw of the Japanese attack broke under the weight of a daring defense. The Seventh Fleet first stunned the attack with waves of PT boats, then stopped it cold with destroyers, and finally crushed it altogether using cruisers and battleships. The northern strike force sailed within range of the landing beaches, then withdrew under the false impression that both U.S. fleets were still in the area.

The landings at Leyte fulfilled Douglas MacArthur’s promise to the Philippine people. His “I have returned” address remains one of the most revered speeches in Filipino history.

Leyte Gulf was the implied end of Japanese rule on the expansive Philippines and the irrefutable end of the Japanese navy. It was also the last engagement between battleships ever and, in fact, the largest naval battle in world history. Oddly, it was also the first truly coordinated operation between the two senior officers in the Pacific, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Adm. C

HESTER

N

IMITIZ

In the battle of Leyte Gulf, the escort carrier USS

St. Lô

went down after being hit by a Japanese plane, making it the first of eighty-three Allied ships in the war to be sunk by kamikazes.

9

. IWO JIMA (FEBRUARY 19–MARCH 26, 1945)

Called “Sulphur Island,” Iwo Jima was a pear-shaped volcanic creation five miles across and a vital airbase to the Japanese. With rancid water, putrid air, radiating heat, and minimal vegetation, it was a miserable assignment for its defenders and a deathtrap for anyone wishing to invade it.

But by the fall of 1944 the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff determined the island to be of absolute importance. Fuel and reliability problems were downing B-29s faster than the Japanese. The only viable landing site on the thousand-mile bombing run from the Marianas to Tokyo was Iwo Jima. Japan’s “unsinkable aircraft carrier” had to be taken.

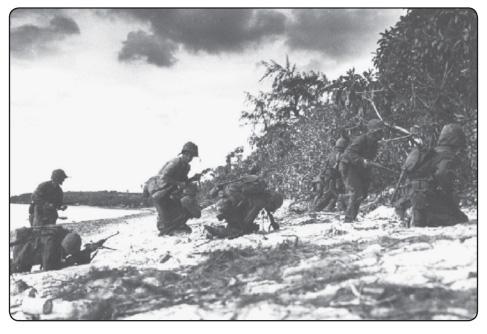

As the Fourth and Fifth U.S. Marine divisions quickly learned, as would the reserves to follow in their wake, days of naval shelling and months of bombing raids had done nothing to push the Japanese from hives of subterranean fortifications and caves. The Americans landed against minimal opposition, gaining several hundred yards and amassing thousands of men on the beachhead. Then the island defenders opened up with mortars, antitank guns, and machine guns. There was no cover; it was nearly impossible to dig foxholes in the soft volcanic ash. Assault vehicles became trapped in the formless soil.

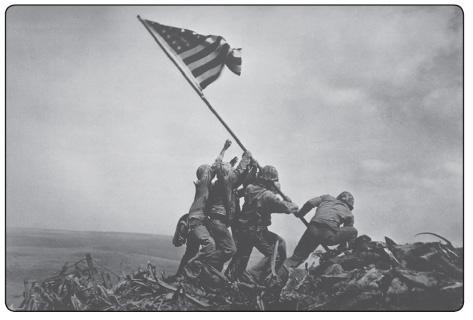

Joe Rosenthal captured an immortal moment in this photo atop Mount Suribachi on day five of the battle, yet Iwo Jima would not be secured until day thirty-six.

By nightfall six hundred marines were dead, but the island had been cut in two. The following day, the Fifth Marines pushed south up Mount Suribachi, and the Fourth Marines fanned north to secure the airfields. Three days later, five marines and a navy medic planted a large American flag atop Suribachi, and photographer Joe Rosenthal captured the most famous image in American military history. In a grand sweep north, the Third Marine Division joined in the fray. Still, a month of brutal fighting lay ahead. Even as B-29s began making emergency landings after long bombing missions against Japan, ground troops were still mopping up heavy pockets of resistance. Not until the end of March was the island finally declared secured.

In killing nearly the entire Japanese force of 23,000, almost 7,000 Americans died. Yet by the end of the war, more than 2,200 B-29s made emergency landings on Iwo Jima, sparing 24,000 U.S. crewmen’s lives.

103

In all, twenty-seven U.S. servicemen won the Medal of Honor on Iwo Jima, twelve of them posthumously, a total more than any other battle in the Second World War.

10

. OKINAWA (APRIL 1–JULY 2, 1945)

It was the last stop on the island-hopping campaign. Shaped like a serpent heading southwest, sixty-mile-long Okinawa held nearly eighty thousand Imperial soldiers, most of them positioned on high ridges across the serpent’s neck. On April 1, 1945, a half-million U.S. servicemen, plus an attack fleet from the British Royal Navy, essentially surrounded the reptile and thrust one hundred thousand men into its right side.

104

Landings and advances north progressed well for the Americans. Troops reached the snake’s tail in two weeks. But the push south quickly turned bloody. Bombings and barrages failed to dislodge the Japanese from caves along the high ground. Mortars and artillery leveled the Americans from afar; grenades and machine guns slaughtered at close quarters. The long delays caused Allied naval support to remain in position, drawing hundreds of successive kamikaze attacks. On land the Japanese held out until an ill-advised banzai charge separated their lines, signaling the beginning of gradual disintegration. The following six weeks witnessed savage fighting in the skull of the snake—storms of artillery fire, roving packs of flamethrowers, and suicides. Discipline evaporated among the surviving Japanese, who began to turn on each other and against civilians. By late June most of the original garrison was dead.

105

The battle of Okinawa killed or wounded 10,000 U.S. Navy personnel, mostly through kamikaze attacks. American marines and soldiers suffered 40,000 killed and wounded. All told, nine out of ten Japanese troops died. As many as 20,000 pro-Japanese native militia and 60,000 civilians perished.

The empire had lost the last remnants of its navy and most of its remaining aircraft, but that hardly insinuated an easy Allied victory in the impending invasion of Japan. Of the losses in the fight for Okinawa, 90 percent occurred on land.

106

Along with the U.S. and Japanese banners, a Confederate flag flew over Okinawa. A U.S. marine lofted the Stars and Bars atop Shuri Castle after the stronghold fell to the Americans. Some claim the flag was in honor of the commanding officer, Gen. Simon B. Buckner Jr., whose father was a general in the Confederate army.