The History of Florida (93 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

MacManus, and Dario Mareno (Tal ahassee: John Scott Dailey Florida Institute of Gov-

ernment, 2004), pp. 1–64.

27. MacManus, Jewett, Dye, and Bonanza,

Politics

in

Florida

, 3rd ed., p. 111.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid., chaps. 4, 7.

30. Susan A. MacManus, “V. O. Key Jr.’s Southern Politics: Demographic Changes Will

Transform the Region: In-migration and Generational Shifts Speed up the Process,” in

Unlocking

V.

O.

Key

Jr.:

Southern

Politics

for

the

Twenty-First

Century

, ed. Angie Maxwell

& Todd G. Shields (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011), pp. 198–200.

proof

23

Florida’s African American Experience

The Twentieth Century and Beyond

Larry Eugene Rivers

A mere forty years after slavery’s demise, the president of the United States

came to Florida to celebrate the progress made by a race. “The event is one

that appeals to the loftiest patriotism of every colored man in Florida,” a

Jacksonville man recorded. “It matters not whether the President will speak

one minute or not,” he continued. “It is al sufficient to know he wil be

there.” With encouragement from city councilman Judson Douglas Wet-

proof

more, Theodore Roosevelt had chosen Florida Baptist College as the site for

his October 1905 remarks. A parade through Jacksonville led by fraternal,

sororal, veterans, and civic organizations preceded Wetmore’s introduc-

tion of the president to Florida Baptist’s distinguished president Nathan W.

Collier and other educators, dignitaries, and community leaders. “What a

pleasure it has been, in driving through the streets to have the Governor

and mayor point out to me house after house owned by colored citizens,

who, by their own energy, industry and thrift, have accumulated a small for-

tune honestly and are spending it wisely,” Roosevelt commented in remarks

that, while pointed, lasted more than the acceptable one minute. “I say, all

honor to teachers, all honor to preachers, but it is almost impossible that the

whole of any people can be teachers or preachers,” the president ultimately

observed in conclusion. “The bulk have got to be men who fol ow trades

and mechanical pursuits, who are first-class farmers, first-class tradesmen

and carpenters, and who excel in any of these respects, and every man who

makes that kind of good farmer or thrifty, progressive, saving mechanic,

who gets to own his own house, to be free from debt, to be able to keep his

wife as she should be kept. Every such man is not only a first-class citizen of

this country, but is doing a mighty work in helping uplift the race.”1

· 444 ·

Florida’s African American Experience: The Twentieth Century and Beyond · 445

proof

A family portrait by Vansickel Studios in Gainesville, 1900.

Given the tenor and direction of his remarks, President Roosevelt would

have been hard-pressed to find a more apt setting than Jacksonvil e and Flor-

ida. In four short decades, the Sunshine State’s African American residents

had transitioned from conditions of abject servitude to a level of economic

gain and merited respect almost unparalleled elsewhere in the South. In the

process, their numbers, institutions, and possessions had swelled in magni-

tude to truly impressive figures. From a total of only about 92,000 black per-

sons resident in 1870, for instance, African Americans would boast in 1900

a figure that topped 265,000. That amounted to over 43 percent of the total

population at a time when the overwhelming majority of Floridians still

446 · Larry Eugene Rivers

lived within 50 miles of the Georgia state line. Twelve of forty-eight coun-

ties contained black majorities in 1900. These included Alachua, Columbia,

Duval, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Nas-

sau, and Wakul a. This predominance found its echo in many of the state’s

principal towns and cities. As late as 1915, eleven of the incorporated places

having populations of 1,000 or more held greater numbers of African Amer-

icans than whites. Numbered among them were Jacksonville, Tal ahassee,

Apalachicola, Daytona, Fernandina, Palatka, Quincy, Sanford, Green Cove

Springs, Marianna, and Monticello.

In many respects, Jacksonville and Duval County stood at the summit of

Florida’s African American world. By far the state’s most populous city and

county, they contained within their limits achievements, circumstances, and

conditions that many African Americans earnestly hoped would represent

the future of the race. “Jacksonville in the Lead” a feature article in a nation-

al y circulated race newspaper proclaimed in 1901.2 Its correspondent waxed

eloquent describing a thriving middle class based in part upon successful

businessmen and proud professionals. Not forgotten were tradesmen and

artisans, particularly carpenters, timber industry workers, and longshore-

men. Service workers who catered to the burgeoning tourism industry be-

longed as wel . James Johnson, the father of the writer, poet, lawyer, and

proof

race leader James Weldon Johnson, proudly served as a Baptist preacher,

but he, with wife, Helen, raised their sons with his earnings as headwaiter at

Jacksonville’s posh St. James Hotel.

In a state of towns and cities pulsing with growth, opportunity abounded

and rewards attended determined efforts. In the circumstances it did not

appear all that unusual in 1901 when Jacksonville carpenter M. A. B. Brooks,

with the gains of his Jacksonville labors, dispatched his son Charlie Brooks

to the Meharry Medical School at Nashville or that banker Sylvanus H. Hart

the next year would enroll Sylvanus H. Hart Jr. at New England’s Phillips

Exeter Academy. Meanwhile, black lawyers such as one-time state senator

and Florida Reconstruction historian John Wal ace might represent white

clients just as black physicians, medical-school educated at a time when

many white physicians lacked such formal training, treated white patients. It

cannot be denied that poverty existed or that some individuals either lacked

initiative or were inclined to crime to earn their living. The same state of

affairs, though, existed among whites.

The very existence of Jacksonville’s good schools—institutions that cre-

ated educational legacies visible in the present day—offered an eloquent

defense to a mounting chorus of racist voices that proclaimed without

Florida’s African American Experience: The Twentieth Century and Beyond · 447

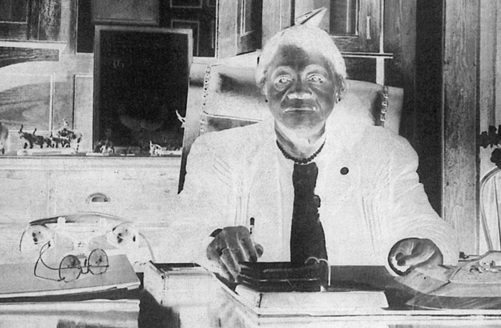

Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, president of Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach,

is shown at her desk in this photograph by Gordon Parks in February 1943. Daughter of

former slaves in South Carolina, Dr. Bethune founded the Daytona Literary and Indus-

trial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904, which merged with the Cookman Institute

of Jacksonville in 1923. Until her death in 1955, she was Florida’s best-known African

American educator.

proof

foundation the inferiority of the black man. Florida Baptist Col ege (or

Academy), where President Roosevelt spoke, ultimately would serve along

with the Florida Institute of Live Oak and Florida Normal Collegiate Insti-

tute of Saint Augustine, as parent institutions of Florida Memorial College,

now of Miami. The venerable Cookman Institute, a northern Methodist

school founded in the 1870s, continued its traditions of service at Jackson-

ville into the twentieth century. In 1922, it merged with Mary McLeod Bet-

hune’s Daytona Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls to

create Bethune-Cookman College of Daytona Beach. Moreover, the African

Methodist Episcopal Church late in the nineteenth century had sparked the

creation of Edward Waters Col ege. That institution also has pursued its

mission on behalf of young people for well over a century.

These certainly were not the only schools of consequence in Florida or

even Jacksonville. The State Normal and Industrial College for Negro Stu-

dents at Tal ahassee held premier status. Tracing its beginnings to 1887, the

institution would emerge in 1909 as the Florida Agricultural and Mechani-

cal College for Negroes, reflecting its special status as the state’s only 1890

448 · Larry Eugene Rivers

land grant institution. The name changed again in 1953 to become Florida

Agricultural and Mechanical University. It remains the only publicly funded

institution of higher learning for African Americans in Florida, as well as

the nation’s largest historical y black college or university. This is not to say

that, at the twentieth century’s dawn, the State Normal School had no com-

petition. In that category could be listed the Jacksonvil e institutions already

mentioned, as wel as Eatonvil e’s Robert Hungerford Normal and Industrial

School, founded in 1889 and modeled after Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute.

The Hungerford School today is operated as a public school by the Orange

County School District.

At the twentieth century’s beginning, black Floridians thus continued

to embrace an appreciation for the power of education and il ustrated that

commitment through the institutions they supported. At a time when high

schools could not be found in many white communities, African American

schools at or approaching that caliber existed in many of the larger cities

and towns. Typical y, white-dominated school boards underfunded these

institutions, leaving responsibility to black residents for making up the dif-

ference. The Stanton High School (once the Stanton Institute) at Jackson-

vil e provides a good example. Founded with assistance from the Freedmen’s

Bureau and the American Missionary Association, it soon became a public

proof

institution that drew generations of students from the city and state. Simi-

larly, children from throughout Florida sought out the Fessenden Academy

at Martin near Ocala, an institution that dispatched its graduates to colleges

and universities throughout the United States. In many places, the names

and legacies of such schools live on. Representative of them were Lincoln

Academy at Tal ahassee; Union Academy, Gainesville and Bartow; Harlem

Academy, Tampa; Howard Academy, Ocala; Central Academy, Palatka;

Hopper Academy, Sanford; Douglass School, Key West; and Washington

High School, Pensacola.

As Florida evolved into the most urban of southern states in the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African Americans contributed

to the dynamic in a variety of ways that might surprise residents today. His-

torian Canter Brown has pointed out that town and city governments run

or heavily influenced by Republicans and sometimes dominated by black

officeholders evidenced the foresight to plan for an urban future by bonding

for water, sewerage, and electric power systems and otherwise to facilitate

modern improvements such as paved streets and street railways. Democrats

castigated the visionaries as spendthrift, at best; yet, with the future beckon-

ing, the conservatives were forced to adopt the models pioneered by others.

Florida’s African American Experience: The Twentieth Century and Beyond · 449