The Hop (15 page)

HE'D TRAVELED FOR A LONG TIME in the stuffy darkness of a hard nest. He was jostled, lifted, tilted, banged, and bumped. Sometimes the girl sprinkled some stale little crickets into the nest.

When the cover finally came off and he saw the night sky, Tad nearly fainted with joy. A light warm mist fell on him, and he just sat there soaking it up. It softened his skin and trickled into his cracks. It fluffed him up and made him feel toadly.

The girl lifted him out of the nest. Blurry gray clouds floated near the ground. The wet grass touched his belly, and he made a little hop. Human feet were nearby, but he knew they wouldn't hurt him.

In a clump of clover, he found five ladybugs and a curly, tender earthworm

. Zot, zot, zot

and triple

zot,

just like that!

This place was nice, he could tell. A lot like home. But now he knew how big the world was, and understood that his chances of finding Toadville-by-Tumbledown were slim to none, unless he was right about one important thing: that he and the girl lived in the same garden.

The humans eventually went away, and Tad sat in the clover. He could see a pond down the bank, its surface dancing with raindrops. It could be his pond. It looked like his pond.

And then he saw Cold Bottom Road on the other side of the clover patch.

Tad began to hop faster, feeling the pollen cling to his wet body. There were dried lilac petals under the bush just where he might find them. And then, to his right, a bit up the hill, was the outline of Toadville-by-Tumbledown. And just beyond it lurked the grim shadow of Rumbler.

But thank the green grass. Oh, thank the green grass. His home was still here!

“Hello!” he called. “Hello!”

A handful of young hoppers were out gathering night crawlers in the rain. “Tad? Is that you?” somebody called.

“It's me,” he cried. “I'm back! I'm home!”

The news spread quickly, and toads came tumbling out of Toadville-by-Tumbledown, hopping up Cold Bottom Road.

“We thought something had happened to you!” Tad couldn't tell the voices apart, they came so fast. “We thought we'd never see you again.”

Well, he thought he'd never see

them

again either. But here he was. Tad felt as if all the joy in the world glowed inside him.

The clamor continued until an old toad came out to greet him officially. “Welcome home, Tad,” he said, his voice deep and hoarse.

Where was Seer? Why didn't the young hoppers go get him and bring him out?

“What took you so long to get back?” somebody demanded. “Where's Buuurk?”

“Buuurk was very brave,” Tad said, seeing Anora in the crowd. She was beside Shyly. “He gave his life trying to help me kiss the queen. He was taken up into the Great Cycle. I went on.”

The toads looked at him, their eyes shining in the rain. Someone called, “Buuurk was very brave.” Anora said, “He was a great singer.”

“He was a good friend,” somebody else added.

“He was my best friend.” Tad felt the empty space beside him just as sharply as he felt the jewel of dreams growing behind his eyes.

“But did you kiss the queen?” one of the old toads asked. “Are we saved?”

“Yes,” he said.

Rain dripped from the tree overhead. Otherwise Tumbledown was silent, and Toad wondered if he'd even spoken.

Then the toads broke into shouts. “We're saved! We're saved! He kissed the Queen of the Hop!”

“I'd like to talk to Seer,” Tad said when the ruckus had died down.

The silence became as thick as the misty sky. Finally Anora said, “We celebrated his lifting up into the Great Cycle two moonrises ago. We lined the hall with purple phlox. We remembered his prophecies and his wisdom.”

Tad felt as if a big rock had fallen on him.

After a while, a chant began very quietly. “Long live the Seer, long live the Seer.” All of the toads were looking at him.

IT HAD ONLY BEEN TEN DAYS since she'd seen her grandmother, but Taylor felt as if she'd been gone for months. Her grandmother looked thinner. But her hug was as good as ever.

“We brought you a ton of stuff,” Taylor told her. “Wait till you see.”

All the souvenirs were in a big black canvas tote with reno written in rhinestones. Taylor's mom put it on the table.

“Now, this is the first thing.” Taylor took out a CD of Ryan and the Rompers. “This is Mom and Dad's band.” She put it on the table in front of Eve. “And look. They had this up during the whole festival.” She unrolled the poster she had seen the first night of her dad on drums and her mother singing.

Her grandmother smoothed back the curling edges of the poster, then looked at Taylor. Her eyes were pleased. “I think you had fun.”

“Well, yes. But look at what I bought for you. With my own money.”

Her grandmother unwrapped the T-shirt that Taylor had rolled carefully in tissue paper and tied with ribbon.

“Do you like it?” Taylor asked, her fingers crossed.

Eve held the T-shirt against her front and looked down at the toad logo. “I love it! Thank you, Taylor. Did you see John Verdun in the hotel?”

Taylor shook her head.

“I saw him entering the lobby with his entourage one night,” her dad said. “And I heard he dropped another billion or two on his ecology foundation.”

“Put the shirt on,” Taylor urged her grandmother. “We can take some pictures. Then we can add them to the album you gave me before we left.”

“I can't believe you kept all those old pictures and clippings,” Taylor's mom said.

Eve smiled. “They were happy times. Most of them.”

Well, of course, it hadn't been happy when Taylor's grandfather got killed so young.

“It's happy music,” Taylor's dad said. “Come on, Taylor, show Eve your crown and sash. I've gotta get going.”

Was she hearing stuff, or had her dad called her Taylor? She was just starting to like Peggy Sue.

She took the sparkly tiara out of her tote and handed it to her grandmother. “It's kind of big,” she explained. “It slides off my head.”

Her grandmother turned it so the stones caught the morning sunlight. “It will fit better next year.”

“And here's the sash,” Taylor said, spreading out the wide red satin ribbon that proclaimed her the Queen of the Hop.

“Look, I hate to say this, but I've really got to hurry,” her dad said.

“Me too,” her mom added. “Stacks of files will be towering on my desk. What about we take some pictures first, though?”

“Outside. In the garden,” Taylor said. She knew there was no stopping a parent in a hurry. This morning they'd turned on their BlackBerrys, laptops, pagers, beepers, and whiners.

As they went out, Taylor saw the earthmoving machine parked by the old tumbledown shed. She'd glimpsed it in the rain last night. She could still try to save the pond by talking about it on television, but she understood that you couldn't always make things be the way you wanted them to be.

She said to her grandmother, “Maybe we'll see my toad. Did you hear us last night when we came to turn him out into the grass? It was after midnight. That was my special present. I'll tell you all about it later.”

Off the back deck, the billowing white baby's breath was almost up to Taylor's waist. “Whoa! That's gotten big. Let's take our pictures standing by that.”

So they took pictures of Taylor in her crown and sash standing by the baby's breath. Taylor in her crown and sash, standing between her parents. Taylor and Eve in their matching toad shirts.

Then Taylor took pictures of her grandmother and her parents. In the last one, Taylor's mom wore Taylor's rhinestone crown, and her dad wore the red sash.

“Wait! Don't go away,” Taylor said, after she snapped it. “We need the hula hoop.”

She ran to the car and got it and hung it around her dad's neck along with the sash.

“Now, that's a picture!”

Her mother took off the crown, her dad lost the sash and hula hoop, and they were gone before Taylor could say

rock and roll.

And now, finally, Taylor had her grandmother to herself.

They sat down in the grass. Eve hugged her knees, and Taylor copied her grandmother. She leaned against her side. Her grandmother put her arm around Taylor. They still fit like a lock and key.

Down the hill, paddling ducks made Vs on the pond. A cawing crow flew from one mulberry tree to another

.

Clematis sprawled down the pond bank and grew up on supports. Daylilies caught the sun.

Her grandmother squeezed her. “Tell me every little detail of the trip.”

Taylor did, trying to leave nothing out. All about the toad and the dance contest and Diana, last year's queen, and Number 11. About Tad and how he was a little odd, but also nice, and really into the environmental thing. “I poured water over my head the last night,” Taylor confessed. “Because he did it. And it was fun.” Later, she might tell her grandmother about the kiss.

Eve smiled.

Taylor gazed over the field. From where she sat now, things looked undisturbed. But down the hill, the woods were all torn up. She'd seen it this morning. It made her heart hurt. But if her grandmother could survive whatever was going to happen, Taylor could too.

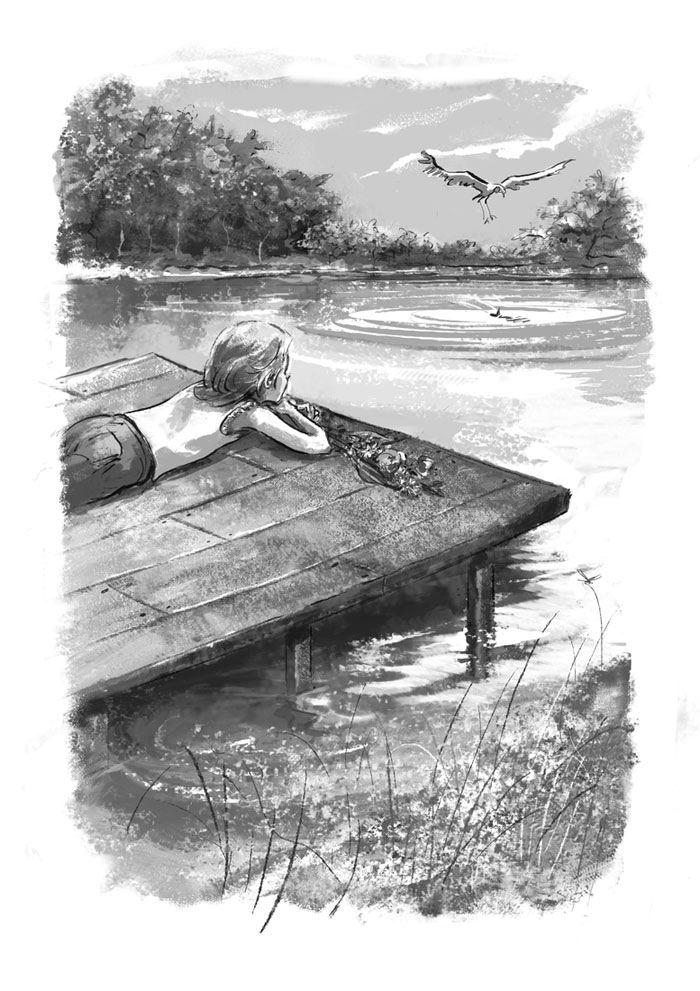

That afternoon while her grandmother was napping, Taylor walked down to the pond. She lay on the dock and stared up at the clouds, then turned onto her stomach and stared into the water. A school of little fish, their bodies almost clear, shifted and darted. She and Kia had lain here for hours last summer, waiting for fish to swim into their nets. This would be the very last summer. Actually, it could be the last day. She shut her eyes, trying to store everything she loved about the pond in her memory.

She opened her eyes when a heron came in for a landing, its body a T-shape as it dropped its long legs. A fish leaped, sending circles across the pond. Taylor bounced the toes of her sandals against the dock, then quit, wanting the world to be totally quiet. She could hear the little waves making their way to shore, then finally that stopped, and all she could hear was her blood moving around inside.

But then a bullfrog began its silly thrumming call, so loud it made her laugh and forget how solemn and sad she had been feeling. Across the pond, another bullfrog spoke. A breeze stirred her bangs. Taylor yawned. She made a cradle with her arms and rested her head against them. She thought of the little toad she had brought home, and of the boy who had made her promise to look for the blue topaz beetles.

As she walked back up the hill to the house, she stopped at the old tumbledown shed, which was full of rotting wood. She pulled back the clematis vine that curled around the old posts. At first she only saw scurrying ants, but then, near a hole where the wood had rotted almost totally away, she caught a flash. It flew, but not before she saw that it was a little beetle, so bright it looked like a piece of pale blue glass.

IN THE HALL OF YOUNG HOPPERS, a golden light fell through the translucent pebbles. Usually Seer would be settled on his pile of milkweed fluff, telling his dreams, drawing the young hoppers out to be their best, whatever that was. Buuurk had been his bestâa toadly brave and strong friend. Tad still felt lopsided without Buuurk.

“So what did you see out there?” one of the young hoppers asked Tad.

Shyly asked, “How far did you go?”

“Mother Earth is much bigger than what we can see from the top of the mulch pile,” Tad told them.

Murmurs of surprise drifted through the toads.

“Did you hop all the way?” someone asked.

“I hopped a lot. And I moved for several sunrises in a roaring stinky thing with a turtle shell on its back. And once I went fast beneath the foot of a small human. I was in many different nests, and some of them moved around.”

“What's a roaring stinky thing?”

Tad explained the best he could.

The hoppers gazed at him, their eyes full of dazzlement and doubt.

“I sat among the stars,” Tad said, “and looked down on Mother Earth.”

“No,” several toads said.

“And I could see that much of Mother Earth is already covered.”

A tremor went through the hoppers, and some of the younger ones peed.

“Buuurk and I found another toadville too. The toads there were good to us.”

After murmurs of amazement, Shyly said, “So, we're not alone.”

“Coverings are very close to their toadville,” Tad said.

“Rumbler still has his big stinky feet right by us,” somebody said. “So how do you know we're saved?”

“Because I kissed the Queen of the Hop,” Tad said. And he could only hope that she would keep her promise.