The Hop (2 page)

BECAUSE THERE WERE NO OTHER TOADS around to lead the way, Tad almost missed the toad hole. It was small and hidden in the shadow of a rotten post. He dropped into it as fast as a gnat could blink.

Where was everybody? Sunlight fell through both ends of the empty corridor. Tad hurried along. Usually, on the first day, the corridor was packed with jostling hoppers, ready for spring.

Then he heard gossipy croaks drifting from the Hall of Old Toads. After the silence it was a relief. At least he was just late, and not all alone. But his warts prickled.

Faint voices came from the Hall of Young Hoppers. He was so late, Seer might have already started the Telling.

Tad passed the nursery, silent and empty, ready for the newbies who would come out of the pond in midsummer. Tad had once wanted to keep his tail and stay in the pond forever. He loved the warm shadows of the water. And he had stayed a tadpole for longer than anybody else that summer. But one morning, his tail had fallen off and his legs had carried him up Cold Bottom Road to Tumbledown.

Late, late, late. Tad raced along the corridor, the path lit by skylights of translucent pebbles. Root fingers curling from the walls grabbed at him.

He stopped outside the hall.

He wanted to burst in. See everybody. Be welcomed home. Ask Seer what the stories in his sleep meant. But Seer would probably scold him in front of the other hoppers for being late.

A toad in

time saves nine,

Seer always told him.

Your friends

have to be able to count on you, Tad.

And maybe the hoppers would be able to tell, just by looking at Tad, that he had been restless inside Mother Earth's belly. So Tad eased into the room.

The old prophet rested on a pile of milkweed in the center of the crowd. His prophet hat hung on the bony ridge between his ancient eyesâeyes that no longer saw clouds or moonlight or moths or Tad. Yet Seer saw things that others didn't. Dreamed things that welled up from deep pools. Predicted things that seemed unlikely.

Seer's milky eyes, like two spring moons, settled on Tad. “The last of our young hoppers has finally arrived.”

Somebody whispered, “Seer's blind as a stone. How does he know to the exact flicking tongue who's here?”

Tad bounced forward and thumped the ground three times in a sign of respect. “Greetings, Seer.”

Seer looked even more ancient this year, the great ridge between his eyes bulging and ragged. As his hands touched Tad's head in blessing, the old prophet jerked like he had touched a thorn. Could he feel the spot that burned behind Tad's eyes?

Tad needed to talk to Seer, but not with the other toads around.

Sending up a little cloud of fluff, Seer collapsed back into the milkweed.

Buuurk bumped Tad. “Thank the green grass, toad! I thought a groundhog had got you!”

Tad looked at his best friend. “I just slept too long. How did you sleep?”

“How did I sleep?” Buuurk blinked. “What kind of question is that? I shut my eyes and then I opened my eyes.”

“Me too,” Tad lied. He didn't want Buuurk to think he was a freak, like the seven-legged cricket they had found in the mulch pile last summer.

Anora, beside Buuurk, nodded. “I told Buuurk not to worry. You do things at your own speed.” Her eyes danced in their frames of pretty white warts. Even Anora, who was a summer younger than Tad, knew how he'd gotten his name. Tad was short for tadpole, which was what he'd wanted to stay for as long as he could.

Seer righted himself. “Everybody is here,” he said. “We will begin.”

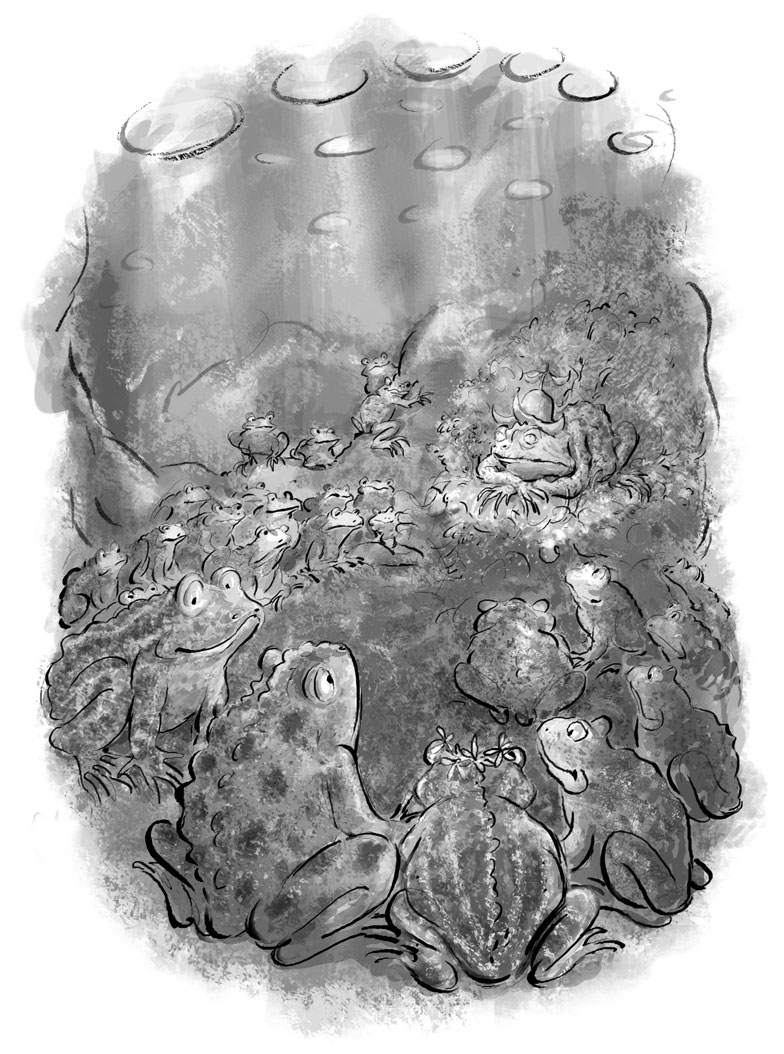

Still twitchy from his hurry, Tad took his usual place between Buuurk and Anora. All the young hoppers' faces turned toward Seer like moonflowers to the moon. The light falling through the translucent pebbles was soft behind the old prophet as he began the Telling of who the toads were and how they came to be.

“In the beginning, when there was nothing much in the darkness but a smile, Mother Earth and Father Pond found each other.”

Tad could hardly make out Seer against the brightening light, but Seer's voice was strong as he told the story the exact same way he always told it, word for word. Tad could practically tell it himself. The next part was how Mother Earth and Father Pond made the sun so they could see each other.

“And they made the moon to play with the sun,” Seer intoned. “They made the stars”âTad's mouth moved along with Seer's next wordsâ“and named each one.” Tad loved that part. He wished he knew all the stars' names.

Seer told about the making of the trees and flowers and grass.

And here came the very best part! Tad bumped Buuurk.

“One day, they made a swirl of tadpoles to delight Father Pond.⦔

Yes, yes, Tad knew. Mother Earth wanted the tadpoles, but Father Pond wouldn't give them to her, so they had a big fight with lots of thunder and lightning.

“In time,” Seer explained, as he always did, “they decided to share. Mother Earth pinched off the tails of a few tadpoles and gave them legs so they could walk on her belly. She called the beautiful, breeping creatures her

toads,

her Jewels of Creation.”

Tad glanced around at the faces shining with pride. He squirmed next to Buuurk.

“Mother Earth loved her toads so much that she gave them Toadville-by-Tumbledown, with nice rotting wood, a mulch pile, and a garden full of bugs and worms.”

A voice cried from the back, “And she thought the toads were so wonderful that she pressed the shape of a toad on the face of the moon.”

“Shhhh!” somebody said. “Let Seer tell it.”

“She did do that,” Seer said. “And to show how much she loves her toads, she takes them back into her belly every year before Father Pond covers her with snow. But she returns them to the garden when the snow melts so Father Pond can enjoy them too.”

The creation story always made Tad forget everything except how perfectly splendid he was. Mother Earth and Father Pond's own jewel.

“We are the toads!” a few of the rowdier young hoppers in the back chanted. “We are the toads!”

“And almost all of us came back to life,” Anora told Tad. “We counted heads before you got here. Only one very, very old toad didn't make it.” She reached out her hand to touch Tad. “Did a mole step on you while you slept? What's that bump behind your eyes?”

Tad ducked, glad that Seer had begun to speak again, and Anora turned to listen.

“We are born of water,” Seer croaked. “Yet we live out our days on the land. And we return to the belly of Mother Earth to be born again.” Seer's face swept over the young hoppers as if he could see them, but his prophet's hat had slid over his blind eyes.

“And it goes on and on,” one of the young girl hoppers behind Tad muttered. “We know.”

“Until you roll snake eyes and a blue racer eats you,” one of the boy hoppers said.

“Or a grackle,” somebody added.

“Or a fox.”

“It doesn't matter,” Anora cried. “We may go into the Great Cycle, one by one. But Toadville-by-Tumbledown will always be here.”

“You tell it, hopper!” somebody shouted from the back.

Why didn't Seer put a stop to their arguing as he usually did? Tad looked at the old prophet. He had shrunk over the winter. A hummingbird could whir by and carry him off.

Finally Seer held up his hand for quiet. “Unless we are bold and brave,” he said, “the Great Cycle will end soon.”

The sudden silence was so vast that Tad could hear a mole passing by on the other side of wall.

“Rumbler,” Seer said. “I told the old toads earlier, but they are like meâtoo old to do anything about it. Rumbler is coming.”

Questions echoed through the hoppers. “Who?”

“Rumbler is as big as many mulch piles.” Seer's old voice was frail and shaky. “He has a cry like twenty lightning bolts fighting with one another. He smells like a mountain of stinkbugs.”

Tad's warts prickled. Could this Rumbler be the monster in his sleep?

“I have felt his belly on the earth. I have heard his bellows. He will come on feet with teeth. He will scrape the grass off the earth, leaving earthworms and grubs to bake in the sun. He will hit the trees, making them shake out squirrels and baby birds. Foxes and groundhogs will try to flee, but he will overtake them and squash them to jelly. And Tumbledown will crumble on our backs.”

Tad put his hands over his eyes, shuddering. Rumbler. So that was the monster's name. Rumbler had been in his sleep. Tad's warts went flat, and the ooze of terror slid out of his skin. Anora was making a noise like a mouse caught in a hawk's talons.

Seer's voice grew more quiet. “When there is nothing left, when Mother Earth's body is bleeding and barren, Rumbler will go after Father Pond.”

A hopper in the back croaked wheezily.

“Rumbler will make a sideways hole in the earth, like a woodpecker's hole in a tree, and Father Pondâheartbrokenâwill slip back into the darkness. And where the hole left by his body was, Rumbler will scoop up Mother's Earth's body and fill the hole. And when everything is dead, humans will lay their covering over Toadville-by-Tumbledown.”

“What's a covering?” Tad gasped.

“To be

covered,

to be buried under the sludgy, hardening gray stuff, is to be cut off from the Great Cycle of life. To be covered is to die forever. It is the end.”

Seer shifted his old body until, except for his prophet's hat, Tad could hardly see him against the light.

“We have to do something!” Anora cried.

“I have felt the strength of Rumbler in my belly as he shakes the earth,” Seer said. “But I have also dreamed things. Mother Earth and Father Pond are trying to show us a way to save Toadville-by-Tumbledown.”

“A way to save ourselves?” somebody cried.

Tad waited. Why didn't Seer tell them?

“A hopper must kiss a human,” Seer said.

A hopper must kiss a human.

No, Tad thought. Impossible.

Silence, until someone cried, “Why?”

Humans were uglier than hognose snakes.

“Why can't we kiss a goose or rabbit?” Buuurk cried.

And before a toad could kiss a human, he'd have to catch it.

“A turtle,” Anora said. “I might be able to kiss a turtle.”

Seer gazed at them blindly, the strength of the prophecy written on his face. “To save Tumbledown from Rumbler, a hopper must kiss a human on the mouth.”

“But how will that save us?” Tad asked with dread growing in his heart. There had been a human in his sleep. He remembered now.

“I wish I knew,” Seer said.

“What will happen when a toad”âAnora broke off, unable to say the wordsâ

“does that

?

”

“We must trust Mother Earth and Father Pond,” Seer said.

“Why don't

they

save us?” somebody asked.

“They have shown us the way,” Seer replied. “Now we must save ourselves.”

Buuurk's warts had all but disappeared, and he looked slick and sickly. “I could try, I guess.”

Seer shifted a hand beneath his flabby belly. “Being big and strong is not enough.”

They waited for more, but Seer's prophet's hat had begun to tremble with his snores. So all the hoppers thumped the ground three times in respect and made their way silently along the corridor toward the light of the sun.

“You look like you need some sunshine, toad,” Buuurk finally said.

Tad could hardly croak. “So do you.”

Anora and another girl hopper named Shyly followed them. “Tonight should be the celebration of our return to Tumbledown,” Anora said. “I wonder if we'll still have the feast of First Night.”

“I hope it isn't the feast of Last Night,” Shyly said.

Outside, despite the sun, Tad felt cold to his core. He turned back. “I'll see you later, toads. I have to talk to Seer.”

THE KNEES AND BUTT OF TAYLOR'S JEANS were soaked. Dirt was mashed under her fingernails, and a smear of mud dried on her cheek. From where she sat on the deck, she could see the planted beds down the hill, five in all, where she and her grandmother had worked.

Eve's spring phlox in the neighboring field matched the color of the sky. It was the same color as Taylor's eyes, her grandmother said. Way down in the valley, the new mall made an ugly empty place where a big woods used to be. Taylor got up and moved to a different chair so she didn't have to look at it.

Her grandmother came out with Taylor's favorite cookies and set the bag on the table. Taylor could taste the creamy grit of the maple filling almost before it touched her tongue.

“Our hands are dirty.” Eve sounded as if she didn't care all that much.

“A little dirt makes it taste better,” Taylor said. Her grandmother was the only grown-up who understood that.

“Look.” Eve pointed behind Taylor. “The pond is shivering.”

Taylor turned. Her grandmother was exactly right. The wind had caught the surface of the water and made it shiver. “It has goose bumps,” Taylor said, looking at the little prickles of light that dotted its surface.

“It has geese,” Eve declared, as three geese floated into view.

There was the weedy beach with a swaybacked dock where Taylor and her friend Kia swam in hot weather, and a dam for rolling down. Today the dam showed pale spring grass, but soon it would be snowy with Eve's daisies.

“Mr. Dennis's son stopped by today,” Eve said. “I think he wanted one last look at the place. We walked down to the pond from here, even though he doesn't own the land anymore.”

“But we can still use it just like we always have, right?”

“Let's wait and see.”

When she was little, she'd pretended to be a princess in charge of her kingdom. The squirrels, rabbits, and deer were hers to watch and name and worry about. Plus she had a big private swimming place with lots of interesting stuff in it. When she floated on her back in the middle of the pond, even the cloud shapes seemed like they had been put there to entertain her. She was getting too old to play princess, but Taylor didn't want to give up her kingdom.

“Why didn't we buy it when Mr. Dennis died?” she asked. “It's always been like ours anyway. Nobody but us has ever used it.”

“Couldn't afford it. And what would I do with twenty more acres, Taylor? Two seems like more than enough these days.”

Taylor didn't want to think about what her grandmother meant by

these days.

“Maybe the new owners will be like Mr. Dennis, and not pay a bit of attention to the pond and stuff, and it can still be ours.”

“Maybe,” Eve said. “But it will be their land to use as they please.”

“If they're not nice, I think you should take all your flowers back,” Taylor said. It sounded stupid, but the thought made her feel better.

Eve smiled. “Well, it's not like I planted the seeds, sweetheart. The birds and time did that.”

“Still,” Taylor said, “they're your flowers. If you hadn't had them in your garden first, they wouldn't have moved into the field and made it so beautiful that somebody bought it.” She sounded like a kindergartener; she knew she did. “So it's kind of like we own the field too,” she finished lamely.

“Maybe

kind

of. But my property stops just on this side of the old tumbledown shed, Taylor. The new owners can do whatever they want with the field and woods. And even the pond.”

“What would they do with the pond?”

“Not everybody wants a pond.”

She saw the look in her grandmother's eyes.

Taylor gasped.

“They couldn't! What would happen to those geese right there?” She pointed to the mama goose now trailing goslings in her V-shaped wake.

Taylor went to the south end of the deck and knelt on the bench, trying to imagine her kingdom without the pond. She couldn't.

A sudden breeze slapped her hood against her neck, and she heard the scream of a hawk.

“We should get out the garden hose and fill the birdbaths,” Eve said. “And put up the hammock too. There's so much to do.”

“We better hurry, then. Dad will be here soon.” And he never wanted to wait for anything.

Just then, the single toot of a car horn said he had arrived. Taylor heard his footsteps on the path, and his voice, edgy, talking to somebody on his phone. He waved hello to both of them, yipped a few words into the phone, and clapped it shut. “Ready?” he said to Taylor. “We've gotta hurry.”

Hurry

was his favorite word, Taylor thought.

“I have to change clothes.”

“Nah. Just grab your backpack and let's go. Your mother's waiting at Tortillas. Wanna come, Eve?”

“Thanks anyway. I'm dirty and tired.”

Despite what her dad said, when she was inside, Taylor yanked off her garden clothes. The jeans had left red marks on her waist. She put on her school jeans and shirt, then washed her hands and face. Her dad was nice enough, but if Taylor sprouted a second head he'd just pay for two quick haircuts without wondering a thing about it. He would never notice that her eyes were the color of the spring phlox around the pond.

“See you tomorrow,” Taylor said, finding her grandmother in the kitchen and giving her a hug.

“Not tomorrow. I have the first chemotherapy treatment in the afternoon. They say I'll be tired.”

“I'll come over and make you a snack, then.”

But her grandmother shook her head. “Thanks, honey. I'll manage. We'll see how the first treatment goes. Maybe the next time⦔

“Butâ” Taylor couldn't believe her ears. She always came here after school and stayed until her parents picked her up. And sometimes they worked late and

didn't

pick her up. Which was just fine, because she had lots of stuff at Eve's house.

“We'll work it out, kiddo,” her dad said. He gave her grandmother a quick hug. “Good luck tomorrow.”

Taylor stalked to the car.

As her dad turned out of the drive, Taylor stared over the valley. The sun was almost down. A tiny clipping of new moon dangled in the pale pink sky. Their car curved around the pond dam and down the hill. As her dad turned onto the main road, Taylor saw a sign in the field that hadn't been there yesterday.

PARCELS FOR SALEâZONED COMMERCIAL

. Underneath that was the logo of a company called Central Iowa Realtors.

Taylor knew what the sign meant. It meant another strip mall with another pizza place and another convenience storeâwhen there was already a pizza place and a convenience store just down the street. It meant the loss of her kingdom.