The House of Rothschild (62 page)

Read The House of Rothschild Online

Authors: Niall Ferguson

In the end, of course, Gundermann triumphs: the Banque Universelle collapses and Saccard ends up in jail, leaving in his wake a trail of broken hearts and empty purses.

No one could accuse Zola of having failed to do his homework: not only was the portrayal of James’s office carefully based on an eyewitness account, but the rise and fall of the Union Générale was described with some precision—the mopping up of clerical and aristocratic savings, the bidding up of its own shares and the eventual débâcle. But what Zola had also done was to give literary credibility to the idea that the Union Générale really had been destroyed by the Rothschilds, as well as to the canard that the French Rothschilds had pro-German sympathies. That such notions struck a chord in the France of the Third Republic is all too apparent. Guy de Charnacé’s

Baron Vampire

is as wretched a book as

L‘Argent

is powerful; but its message is not too different. The character of Rebb Schmoul, like Gundermann, is a German Jew with a distinctively racial gift for financial manipulation. A “bird of prey,” he profits from the horrors of war, then metamorphoses into Baron Rakonitz, advising impecunious baronesses in return for their social patronage. Such stereotypes were given added currency by the publication of Bontoux’s own memoirs in 1888. Although Bontoux did not mention the Rothschilds by name, there was little doubt about whom he meant when he denounced “la Banque Juive,” which, “not content with the billions which had come into into its coffers for fifty years ... not content with the monopoly which it exercises on nine-tenths at least of all Europe’s financial affairs,” had set out to destroy the Union Générale.

Baron Vampire

is as wretched a book as

L‘Argent

is powerful; but its message is not too different. The character of Rebb Schmoul, like Gundermann, is a German Jew with a distinctively racial gift for financial manipulation. A “bird of prey,” he profits from the horrors of war, then metamorphoses into Baron Rakonitz, advising impecunious baronesses in return for their social patronage. Such stereotypes were given added currency by the publication of Bontoux’s own memoirs in 1888. Although Bontoux did not mention the Rothschilds by name, there was little doubt about whom he meant when he denounced “la Banque Juive,” which, “not content with the billions which had come into into its coffers for fifty years ... not content with the monopoly which it exercises on nine-tenths at least of all Europe’s financial affairs,” had set out to destroy the Union Générale.

It was, however, another disappointed man—Edouard Drumont—who made perhaps the biggest of all individual contributions to French anti-Semitic mythology. Edouard Drumont had worked as a young man at the Credit Mobilier and had devoted years to researching and writing a huge and rambling tome which purported to describe the full extent of Jewish domination of French economic and political life. First published in 1886 and so successful that it subsequently appeared in 200 editions,

Jewish France

took the notion of a racially determined and anti-French Jewish character and developed it into a pseudo-system. Thus “the Rothschilds, despite their billions, have the air of second-hand clothes dealers. Their wives, despite all the diamonds of Golconda, will always look like merchants at their toilet.” Even the sophisticated Baroness Betty cannot conceal her origins as a “Frankfurt Jewess” when the conversation turns to precious stones. In part, Drumont was merely updating the pamphlets of the 1840s (Dairnvaell was his main inspiration), so that much of his attention in the first volume is devoted to the idea of the Rothschilds’ excessive political power. It is all here: their speculation on the outcome of Waterloo, their immense profits from the Nord concession, their antagonism to the more public-spirited Pereires. Goudchaux—a Jew—saves them from bankruptcy in 1848 and Jews in the Commune protect Rothschild properties from arson in 1871. The politics of the Republic are merely a continuation of this story: Gambetta is in league with the Jews and Masons, Léon Say—“l‘homme du roi des juifs”—plays a similar role, and Cousin, President of the Supreme Council, is merely a cog in the great Jewish—Masonic machine which is the Compagnie du Nord. Even the fall of Jules Ferry can be attributed to the Rothschilds’ malign influence. Best of all, Drumont suggests that the Union Générale was in fact an elaborate Jewish trap, designed to mulct the clericals of their savings.

Jewish France

took the notion of a racially determined and anti-French Jewish character and developed it into a pseudo-system. Thus “the Rothschilds, despite their billions, have the air of second-hand clothes dealers. Their wives, despite all the diamonds of Golconda, will always look like merchants at their toilet.” Even the sophisticated Baroness Betty cannot conceal her origins as a “Frankfurt Jewess” when the conversation turns to precious stones. In part, Drumont was merely updating the pamphlets of the 1840s (Dairnvaell was his main inspiration), so that much of his attention in the first volume is devoted to the idea of the Rothschilds’ excessive political power. It is all here: their speculation on the outcome of Waterloo, their immense profits from the Nord concession, their antagonism to the more public-spirited Pereires. Goudchaux—a Jew—saves them from bankruptcy in 1848 and Jews in the Commune protect Rothschild properties from arson in 1871. The politics of the Republic are merely a continuation of this story: Gambetta is in league with the Jews and Masons, Léon Say—“l‘homme du roi des juifs”—plays a similar role, and Cousin, President of the Supreme Council, is merely a cog in the great Jewish—Masonic machine which is the Compagnie du Nord. Even the fall of Jules Ferry can be attributed to the Rothschilds’ malign influence. Best of all, Drumont suggests that the Union Générale was in fact an elaborate Jewish trap, designed to mulct the clericals of their savings.

Drumont’s later

Testament of an Anti-Semite

(1894) further developed these poisonous ideas, partly in order to explain the limited political achievements of the anti-Semitic movement. Here he adopted a more pseudo-empirical style, calculating how much the Rothschilds’ supposed fortune of 3 billion francs would weigh measured out in silver—and how many men it would require to move it!—and comparing the number of acres of land owned by the Rothschild family with the number owned by the religious orders. If the Boulangists had eschewed anti-Semitism, it was only because “Rothschild had paid [them] 200,000 francs for the municipal elections, on condition that the candidates would not take an anti-Semitic stance,” and because the Boulangist leader Laguerre had personally received 50,000 francs. If the French economy was depressed, it was because “Léon Say ... had handed over the Banque [de France] to the German Jews,” allowing the Rothschilds to lend out its gold to the Bank of England.

4

If France was internationally isolated, it was because the Rothschilds had handed over Egypt to England and financed Italian armaments with French capital. This last charge of lack of patriotism was repeated a few years later in

The Jews against France

(1899). “The God Rothschild,” Drumont concluded, was the real “master” of France: “Neither Emperor, nor Tsar, nor King, nor Sultan, nor President of the Republic ... he has none of the responsibilities of power and all the advantages; he disposes over all the governmental forces, all the resources of France for his private purposes.”

Testament of an Anti-Semite

(1894) further developed these poisonous ideas, partly in order to explain the limited political achievements of the anti-Semitic movement. Here he adopted a more pseudo-empirical style, calculating how much the Rothschilds’ supposed fortune of 3 billion francs would weigh measured out in silver—and how many men it would require to move it!—and comparing the number of acres of land owned by the Rothschild family with the number owned by the religious orders. If the Boulangists had eschewed anti-Semitism, it was only because “Rothschild had paid [them] 200,000 francs for the municipal elections, on condition that the candidates would not take an anti-Semitic stance,” and because the Boulangist leader Laguerre had personally received 50,000 francs. If the French economy was depressed, it was because “Léon Say ... had handed over the Banque [de France] to the German Jews,” allowing the Rothschilds to lend out its gold to the Bank of England.

4

If France was internationally isolated, it was because the Rothschilds had handed over Egypt to England and financed Italian armaments with French capital. This last charge of lack of patriotism was repeated a few years later in

The Jews against France

(1899). “The God Rothschild,” Drumont concluded, was the real “master” of France: “Neither Emperor, nor Tsar, nor King, nor Sultan, nor President of the Republic ... he has none of the responsibilities of power and all the advantages; he disposes over all the governmental forces, all the resources of France for his private purposes.”

Drumont was only the most prolific of a group of anti-Semitic writers of the period who directed their fire at the Rothschilds. Another purveyor of similar libels was Auguste Chirac, whose

Kings of the Republic

(1883) mingled old chestnuts like the myths of the Elector’s treasure and Waterloo with new claims about the Nord line and the Rothschilds’ relationship with the revolutionaries of 1848 and 1870-71. Once again, there was both a racial and a national dimension to the argument: not only were the Rothschilds Jews, they were also Germans—hence their eagerness to despoil France by financing reparations payments in 1815 and 1871. Chirac’s later book,

The Speculation of 1870 to 1884

(1887), was a more sophisticated work which sought to explain the Rothschilds’ recent profits by analysing the fluctuations of bond prices in the period before and after the Union Générale crisis—a not unreasonable enterprise in itself, but compromised once again by its intemperate and unsubstantiated allegations against the Rothschilds and Léon Say. Though superficially empirical, this was in reality just another diatribe against “the triumph of the feudalism of money and the crushing of the worker” and the control of the Republic by “a

king

named Rothschild, with a courtesan or maidservant called

Jewish finance.”

The main allegation made here was that the Rothschilds had conspired to undermine French influence in Egypt for the benefit of England, as part of their historic mission to “kill France” by financial means. The outwardly unremarkable Alphonse was in truth “Moloch-Baal, that is to say the God

Gold,

marching towards the conquest of Europe and perhaps the world, possessing [real] power behind the royal names and political garb, having, in a word, all the profits and avoiding all the responsibilities.”

Kings of the Republic

(1883) mingled old chestnuts like the myths of the Elector’s treasure and Waterloo with new claims about the Nord line and the Rothschilds’ relationship with the revolutionaries of 1848 and 1870-71. Once again, there was both a racial and a national dimension to the argument: not only were the Rothschilds Jews, they were also Germans—hence their eagerness to despoil France by financing reparations payments in 1815 and 1871. Chirac’s later book,

The Speculation of 1870 to 1884

(1887), was a more sophisticated work which sought to explain the Rothschilds’ recent profits by analysing the fluctuations of bond prices in the period before and after the Union Générale crisis—a not unreasonable enterprise in itself, but compromised once again by its intemperate and unsubstantiated allegations against the Rothschilds and Léon Say. Though superficially empirical, this was in reality just another diatribe against “the triumph of the feudalism of money and the crushing of the worker” and the control of the Republic by “a

king

named Rothschild, with a courtesan or maidservant called

Jewish finance.”

The main allegation made here was that the Rothschilds had conspired to undermine French influence in Egypt for the benefit of England, as part of their historic mission to “kill France” by financial means. The outwardly unremarkable Alphonse was in truth “Moloch-Baal, that is to say the God

Gold,

marching towards the conquest of Europe and perhaps the world, possessing [real] power behind the royal names and political garb, having, in a word, all the profits and avoiding all the responsibilities.”

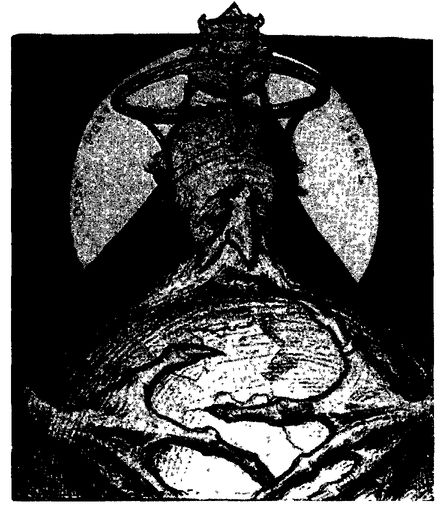

Predictably, such diatribes were accompanied by numerous hateful caricatures, of which the best known is probably Léandre’s

God Protect Israel.

Here Alphonse is portrayed as an emaciated, half-slumbering giant who clutches the globe in claw-like hands and wears on his bald head a crown shaped like the golden calf (see illustration 8.i).

God Protect Israel.

Here Alphonse is portrayed as an emaciated, half-slumbering giant who clutches the globe in claw-like hands and wears on his bald head a crown shaped like the golden calf (see illustration 8.i).

In a similar vein is Lepneveu’s

Nathan Mayer or the Origin of the Billions

which portrays a bearded Rothschild with the body of a wolf lying on a bed of bones and coins on the battlefield of Waterloo (see illustration 8.ii). More crudely, another cartoon (probably from the political left) portrayed “Rothschild” as a giant pig being pulled in a carriage by ragged workers with the caption: “What a fat pig! He grows fat as we grow thin.”

Nathan Mayer or the Origin of the Billions

which portrays a bearded Rothschild with the body of a wolf lying on a bed of bones and coins on the battlefield of Waterloo (see illustration 8.ii). More crudely, another cartoon (probably from the political left) portrayed “Rothschild” as a giant pig being pulled in a carriage by ragged workers with the caption: “What a fat pig! He grows fat as we grow thin.”

8.i: C. Léandre,

Dieu protège Israel, Le Rêve

(April 1898).

Dieu protège Israel, Le Rêve

(April 1898).

Though primarily conpiracy theorists, writers like Drumont and Chirac were also preoccupied with the Rothschilds’ penetration of French high culture and society. In the second volume of

Jewish France,

Drumont devotes a long passage to the château and gardens at Ferrières. The art and furnishings, he concedes, are magnificent; what is lamentable is that so many jewels of French heritage should belong to Jews who can only jumble them together like so much “bric-à-brac.” Nor is it only French culture which the Rothschilds can buy. “This château without a past,” he comments, “does not recall the grand seigneurial lifestyle of the past”; yet the visitors’ book now contains “the most illustrious names of the French nobility.” A prince de Joinville—“a man in whose veins flow drops of the blood of Louis XIV”—abases himself before a mere “money-lender.” At Rothschild marriages, the list of noble names is complete: “[A]ll the [ancient] arms of France... gathered to worship the golden calf and to proclaim before the eyes of Europe that wealth is the sole royalty which now exists.” It is the same story at the costume ball given by the princesse de Sagan in 1885: “this miserable aristocracy” shamelessly rubs shoulders with Mme Lambert-Rothschild, Mme Ephrussi and the rest of “Jewry.” At heart a romantic Legitimist, Drumont regarded the Bourbon and Orléanist nobility as traitors to their Gallic race. It was a theme he returned to in his

Testament,

noting with dismay Charlotte’s purchase of “an abbey founded by Simon de Montfort” (Vaux-de-Cernay), Edouard’s election to the exclusive Cercle de la rue Royale and the presence of the usual grand names at a Rothschild garden party. Chirac too commented sourly on the relationship between the Rothschilds and the elite of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, which had once disdained James and Betty but now accepted their children as social equals.

Jewish France,

Drumont devotes a long passage to the château and gardens at Ferrières. The art and furnishings, he concedes, are magnificent; what is lamentable is that so many jewels of French heritage should belong to Jews who can only jumble them together like so much “bric-à-brac.” Nor is it only French culture which the Rothschilds can buy. “This château without a past,” he comments, “does not recall the grand seigneurial lifestyle of the past”; yet the visitors’ book now contains “the most illustrious names of the French nobility.” A prince de Joinville—“a man in whose veins flow drops of the blood of Louis XIV”—abases himself before a mere “money-lender.” At Rothschild marriages, the list of noble names is complete: “[A]ll the [ancient] arms of France... gathered to worship the golden calf and to proclaim before the eyes of Europe that wealth is the sole royalty which now exists.” It is the same story at the costume ball given by the princesse de Sagan in 1885: “this miserable aristocracy” shamelessly rubs shoulders with Mme Lambert-Rothschild, Mme Ephrussi and the rest of “Jewry.” At heart a romantic Legitimist, Drumont regarded the Bourbon and Orléanist nobility as traitors to their Gallic race. It was a theme he returned to in his

Testament,

noting with dismay Charlotte’s purchase of “an abbey founded by Simon de Montfort” (Vaux-de-Cernay), Edouard’s election to the exclusive Cercle de la rue Royale and the presence of the usual grand names at a Rothschild garden party. Chirac too commented sourly on the relationship between the Rothschilds and the elite of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, which had once disdained James and Betty but now accepted their children as social equals.

8.ii: Lepneveu,

Nathan Mayer ou l‘origine des milliards,

cover of

Musée des Horreurs,

no. 42 (c. 1900).

Nathan Mayer ou l‘origine des milliards,

cover of

Musée des Horreurs,

no. 42 (c. 1900).

It was one of the oddities of the Jewish experience under the Third Republic that a high degree of social assimilation coincided with very public expressions of anti-Semitism. Nor was it merely a matter of outsiders like Drumont carping while royalist aristocrats put prejudice aside; often the very people who socialised with the Rothschilds sympathised with the views propounded by Drumont and Chirac. The almost schizophrenic nature of attitudes towards the Rothschilds can be illustrated with reference to two important contemporary sources: the Goncourt brothers’ journal and Proust’s

A la recherche du temps perdu.

The Goncourts not only shared Drumont’s views; they knew him well. Their journals for the period 1870 to 1896 are full of spiteful anecdotes about the Rothschilds’ “Jewish” character—their materialism, their Philistinism and so on. Yet the Goncourts were also themselves quite happy to accept Rothschild hospitality: discussing French engravings with Edmond in 1874 and 1887, dining with Nat’s widow in 1885, dining with Leonora in 1888, dining at Edmond’s in 1889. It was characteristic of the period that the Goncourts could quote Drumont approvingly less than a year after praising Rothschild cuisine; could dine with Drumont and listen happily to his talk of putting “Rothschild against a wall” in March 1887, then discuss engravings with Edmond that December; could dine at Edmond’s in June 1889, then exchange anti-Semitic anecdotes with Drumont in March 1890, just months before his abortive anti-Semitic call to arms on May 1.

A la recherche du temps perdu.

The Goncourts not only shared Drumont’s views; they knew him well. Their journals for the period 1870 to 1896 are full of spiteful anecdotes about the Rothschilds’ “Jewish” character—their materialism, their Philistinism and so on. Yet the Goncourts were also themselves quite happy to accept Rothschild hospitality: discussing French engravings with Edmond in 1874 and 1887, dining with Nat’s widow in 1885, dining with Leonora in 1888, dining at Edmond’s in 1889. It was characteristic of the period that the Goncourts could quote Drumont approvingly less than a year after praising Rothschild cuisine; could dine with Drumont and listen happily to his talk of putting “Rothschild against a wall” in March 1887, then discuss engravings with Edmond that December; could dine at Edmond’s in June 1889, then exchange anti-Semitic anecdotes with Drumont in March 1890, just months before his abortive anti-Semitic call to arms on May 1.

This world of Parisian salons, in which Jews and anti-Semites routinely mixed, was dramatically polarised in 1894 when Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer on the French General Staff, was accused of being a German spy, court-martialled, found guilty on the basis of forged documents and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island. Alphonse’s reaction to the allegations against Dreyfus was initially one of alarm at the effect the case would have in encouraging anti-Semitism, on the assumption that Dreyfus was guilty; but this soon turned to anger as the evidence accumulated to suggest that Dreyfus had been framed. According to one clerical memoir, Alphonse was “irritated by the condemnation of Dreyfus and by the indifference of the French aristocracy.” However, other members of the family were less willing to be identified publicly as “Dreyfusards,” preferring to try to minimise the schism within their own upper-class milieu.

Other books

What Is Visible: A Novel by Kimberly Elkins

Jerry Junior by Jean Webster

The Forgotten Sisters by Shannon Hale

Stealing Cupid's Bow by Jewel Quinlan

Perfect Pitch by Mindy Klasky

When Sparks Fly (First-Responders Book 1) by Essen, JA

Shrouded Sky (The Veils of Lore Book 1) by A. Akers, Tracy

The Synchronicity War Part 2 by Dietmar Wehr

El taller de escritura by Jincy Willett

The Empty Copper Sea by John D. MacDonald