The House of Tudor (42 page)

Read The House of Tudor Online

Authors: Alison Plowden

Tags: #History, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Nonfiction, #Tudors, #15th Century, #16th Century

In deference to his charge’s fragile state of health, William Howard had planned the thirty-mile journey from Ashridge in very easy stages, expecting it to take five days; but he had reckoned without Elizabeth’s talent for procrastination and it was getting on for a fortnight before the cavalcade began the descent of Highgate Hill into the city. Simon Renard reported that Elizabeth, who was dressed all in white, had the curtains of her litter drawn back ‘to show herself to the people’. According to Renard, she ‘kept a proud, haughty expression’ which, in his opinion, was assumed to hide her vexation’. It may also have masked tear and revulsion - certainly the sights which greeted her as she was carried through Smithfield and on down Fleet Street towards Westminster can have done little to raise her spirits. Gallows had been erected all over London, from Bermondsey and Southwark in the east to Charing Cross and Hyde Park Corner in the west, and the city gates were decorated with severed heads and dismembered corpses - an intentionally grim reminder of the consequences of unsuccessful rebellion.

When Elizabeth reached Whitehall the portents were not encouraging. Mary refused to see her and she was lodged in a part of the palace from which, said Renard, neither she nor her servants could go out without passing the guard. There she remained for nearly a month, a prisoner in fact if not in name. Renard could not understand the delay in sending her to the Tower, since, he wrote, ‘she has been accused by Wyatt, mentioned by name in the French ambassador’s letters, suspected by her own councillors, and it is certain that the enterprise was undertaken for her sake.’

But evidence linking the princess with the insurrection was proving disappointingly hard to come by. Wyatt, who was being rigorously interrogated, admitted having sent her two letters; one advising her to retreat to Donnington, the other informing her of his arrival at Southwark. Francis Russell, the Earl of Bedford’s son, confessed to acting as postman, but the replies, if any, had been verbal and noncommittal. Sir James Crofts, another of the conspirators now in custody, had been to see Elizabeth at Ashridge and had apparently incriminated William Saintlow, one of the gentlemen of her household. But Saintlow denied knowing anything about Wyatt’s plans, ‘protesting that he was a true man, both to God and his prince’. Crofts, too, although ‘marvellously tossed’, failed to reveal any really useful information. Even the discovery of that letter in de Noailles’ post-bag was not in itself evidence against Elizabeth. There was nothing in her handwriting; nothing to show that she herself had given it to de Noailles or had instructed anyone else to do so.

On 15 March Wyatt was at last brought to trial and convicted. Next day, it was the Friday before Palm Sunday, Elizabeth received a visit from Stephen Gardiner and nineteen other members of the Council, who ‘burdened her with Wyatt’s conspiracy’ as well as with ‘the business made by Sir Peter Carew and the rest of the gentlemen of the West Country’. It was the Queen’s pleasure, they told her, that she should now go to the Tower while the matter was further tried and examined. Elizabeth was appalled. She denied all the charges made against her, adding desperately that she trusted the Queen’s majesty would be a more gracious lady unto her than to send her to ‘so notorious and doleful a place’. But it seemed the Queen was ‘fully determined’. Elizabeth’s own servants were removed and six of the Queen’s people appointed to wait on her and ensure that ‘none should have access to her grace’. A hundred soldiers from the north in white coats watched and warded in the palace gardens all that night, and a great fire was lit in the hall, where ‘two certain lords’ kept guard with their company.

The twenty-year-old Elizabeth, lying awake in the darkness listening to the tramp of feet beneath her window, knew that the net was closing around her. Within a very few hours, failing some miracle, she would be in that doleful place from which so few prisoners of the blood royal ever emerged alive. But when the two lords, Sussex and Winchester, came for her in the morning, she made it clear that she was not going to go quietly. She did not believe, she said, that the Queen knew anything about the plan to send her to the Tower. It was the Council’s doing and especially the Lord Chancellor’s, who hated her. She begged again for an interview with her sister and, when this was refused, at least to be allowed to write to her. Winchester would have refused this, too, but the Earl of Sussex suddenly relented. Kneeling to the prisoner, he exclaimed that her grace should have liberty to write and, as he was a true man, he would deliver the letter to the Queen and bring an answer, ‘whatsoever came thereof

It might well be the most important letter of Elizabeth’s life, it might be the last letter she would ever write and she must write quickly, while her escort hovered impatiently in the background. Her pen flowed smoothly over the first page, in sentences polished during a sleepless night. ‘If any ever did try this old saying’, she began, ‘that a king’s word was more than another man’s oath, I most humbly beseech your Majesty to verify it in me, and to remember your last promise and my last demand, that I be not condemned without answer and due proof, which it seems that now I am; for that without cause proved I am by your Council from you commanded to go into the Tower, a place more wonted for a false traitor than a true subject’. Elizabeth had never ‘practised, counselled nor consented’ anything that might be prejudicial to the Queen’s person or dangerous to the state, and she beseeched Mary to hear her answer in person ‘and not suffer me to trust to your councillors’.

It might be dangerous to remind the Queen of Thomas Seymour. Mary would know all about that old scandal and probably believed the worst about it, but Elizabeth decided to risk it. ‘I have heard in my time’, she went on, ‘of many cast away for want of coming to the presence of their prince; and in late days I heard my lord of Somerset say that if his brother had been suffered to speak with him, he had never suffered; but the persuasions were made to him too great, that he was brought in belief that he could not live safely if the Admiral lived, and that made him give his consent to his death...I pray God as evil persuasions persuade not one sister against the other.’

So far so good, but as she turned over the page mistakes and corrections began to come thick and fast. Perhaps Sussex was at her elbow now, urging her to make haste. ‘I humbly crave to speak with your Highness’, scribbled Elizabeth, ‘which I would not be so bold to desire if I knew not myself most clear as I know myself most true. And as for the traitor Wyatt, he might peradventure write me a letter, but on my faith I never received any from him. And for the copy of my letter sent to the French king, I pray God confound me eternally if ever I sent him word, message, token or letter by any means. And to this my truth I will stand to my death.’ There was nothing more to be said, but more than half her second sheet was left blank - plenty of space for someone to add a forged confession or damaging admission - so Elizabeth scored the page with diagonal lines before adding a final appeal at the very end. ‘I humbly crave but only one word of answer from yourself Your Highness’s most faithful subject that hath been from the beginning and will be to my end, Elizabeth.’

As it turned out, she might have saved herself the trouble. When her sister’s letter was brought to her, Mary flew into a royal Tudor rage. She roared at Sussex that he would never have dared to do such a thing in her father’s time and wished, in a triumph of illogicality, that he were alive again if only for a month. Even so, Elizabeth had won a brief respite, for she had managed to miss the tide. The starlings which supported the piers of London Bridge restricted the flow of the river and turned the water beneath it into a mill-race. ‘Shooting the bridge’ was always a hazardous business but when the tide was flooding it became impossible - there could be a difference of as much as five feet in the level of the water. The Council were not going to risk taking the princess through the streets, so it was decided to wait until the following morning. When Sussex and Winchester arrived at nine o’clock there was no question of further delay, but as Elizabeth was hurried through the gardens to the landing-stage, she looked up at the windows of the palace as if hoping to catch a glimpse of the Queen. There was no sign. Mary was in church on Palm Sunday morning. The party embarked at the privy stairs and the barge was cast off and rowed away downstream - down towards the grey, ghost-ridden bulk of the Tower. There her mother had died and her mother’s cousin, poor silly wanton Catherine Howard; her own cousin Jane, with whom Elizabeth had once shared lessons and gone to children’s parties, and so many others - the Seymour brothers, John Dudley, ‘that great devil’ and Suffolk, the weak fool. Behind them rose the wraiths of all those shadowy Plantagenet cousins, sacrificed to make England safe for the Tudors. This had been journey’s end for them all. Was it to be the end of her journey, too?

52 An illustration from the plea roll of the Court of the King’s Bench, Michaelmas 1553, records the defeat of the rebels leading to Mary’s accession.

53 Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, who was burned at the stake in March 1556, painted by Gerlach Flicke.

54 Cardinal Reginald Pole, Papal Legate to England.

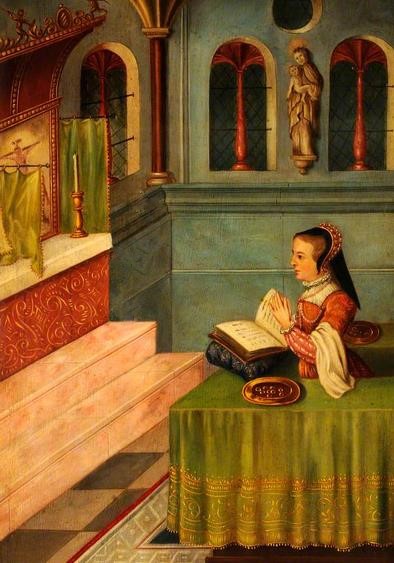

55 Mary exercises her mystic royal power: praying for blessing on rings for curing cramp.

55 Mary exercises her mystic royal power: praying for blessing on rings for curing cramp.