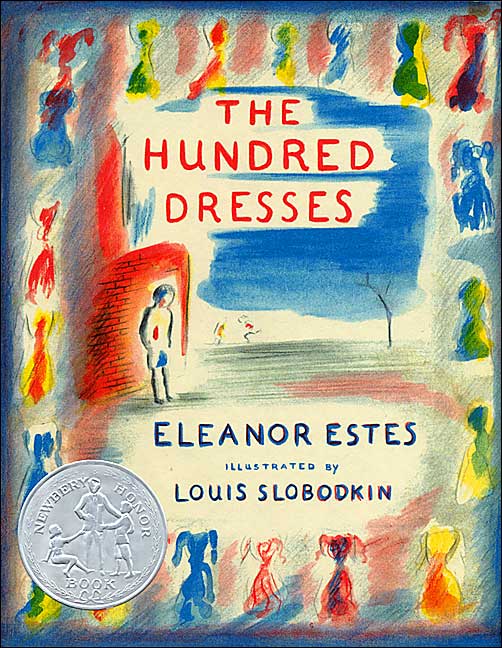

The Hundred Dresses

Read The Hundred Dresses Online

Authors: Eleanor Estes

Eleanor Estes

简介

The Hundred Dresses won a Newbery Honor in 1945 and has never been out of print since. At the heart of the story is Wanda Petronski, a Polish girl in a Connecticut school who is ridiculed by her classmates for wearing the same faded blue dress every day. Wanda claims she has one hundred dresses at home, but everyone knows she doesn’t and bullies her mercilessly. The class feels terrible when Wanda is pulled out of the school, but by that time it’s too late for apologies. Maddie, one of Wanda’s classmates, ultimately decides that she is “never going to stand by and say nothing again.” This powerful, timeless story has been reissued in paperback with a new letter from the author’s daughter Helena Estes, and with the Caldecott artist Louis Slobodkin’s original artwork in beautifully restored color.

Age Level: 6 and up | Grade Level: 1 and up

TODAY, Monday, Wanda Petronski was not in tier seat. But nobody, not even Peggy and Madeline, the girls who started all the fun, noticed her absence. Usually Wanda sat m the next to the last seat in the last row in Room 13. She sat in the corner of the room where the rough boys who did not make good marks on their report cards sat; the corner of the room where there was most scuffling of feet, most roars of laughter when anything funny was said, and most mud and dirt on the floor.

Wanda did not sit there because she was rough and noisy. On the contrary she was very quiet and rarely said anything at all. And nobody had ever heard her laugh out loud. Sometimes she twisted her mouth into a crooked sort of smile, but that was all.

Nobody knew exactly why Wanda sat in that seat unless it was because she came all the way from Boggins Heights, and her feet were usually caked with dry mud that she picked up coming down the country roads. Maybe the teacher liked to keep all the children who were apt to come in with dirty shoes in one corner of the room. But no one really thought much about Wanda Petronski once she was in the classroom. The time they thought about her was outside of school hours, at noontime when they were coming back to school, or in the morning early before school began, when groups of two or three or even more would be talking and laughing on their way to the school yard. Then sometimes they waited for Wanda—to have fun with her.

The next day, Tuesday, Wanda was not m school either. And nobody noticed her absence again, except the teacher and probably big Bill Byron, who sat in the seat behind Wanda’s and who could now put his long legs around her empty desk, one on each side, and sit there like a frog, to the great entertainment or all in his corner of the room. But on Wednesday, Peggy and Maddie, who sat in the front row along with other children who got good marks and didn’t track in a whole lot of mud, did notice that Wanda wasn’t there. Peggy was the most popular girl in school. She was pretty; she had many pretty clothes and her auburn hair was curly. Maddie was her closest friend. The reason Peggy and Maddie noticed Wanda’s absence was because Wanda had made them late to school. They had waited and waited for Wanda—to have some fun with her—and she just hadn’t come. They kept thinking she’d come any minute. They saw Jack Beggles running to school, his necktie askew and his cap at a precarious tilt. They knew it must be late, for he always managed to slide into his chair exactly when the bell rang as though he were making a touchdown. Still they waited one minute more and one minute more, hoping she’d come. But finally they had to race off without seeing her.

The two girls reached their classroom after the doors had been closed. The children were reciting in unison the Gettysburg Address, for that was the way Miss Mason always began the session. Peggy and Maddie slipped into their seats just as the class was saying the last lines “that these dead shall not have died m vain; that the nation shall, under God, have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

AFTER Peggy and Maddie stopped feeling like intruders in a class that had already begun; they looked across the room and noticed that Wanda was not in her seat. Furthermore her desk was dusty and looked as though she hadn’t been there yesterday either. Come to think of it, they hadn’t seen her yesterday. They had waited for her a little while but had forgotten about her when they reached school.

They often waited for Wanda Petronski—to have fun with her.

Wanda lived way up on Boggins Heights, and Bog-gins Heights was no place to live. It was a good place to go and pick wild flowers in the summer, but you always held your breath till you got safely past old man Sven-son’s yellow house. People in the town said old man Svenson was no good. He didn’t work and, worse still, his house and yard were disgracefully dirty, with rusty-tin cans strewn about and even an old straw hat. He lived alone with his dog and his cat. No wonder, said the people of the town. Who would live with him? And many stories circulated about him and the stories were the kind that made people scurry past his house even in broad day light and hope not to meet him. Beyond Svenson’s there were a few small scattered frame houses, and in one of these Wanda Petronski lived with her father and her brother Jake.

Wanda Petronski. Most of the children in Room 13 didn’t have names like that. They had names easy to say, like Thomas, Smith, or Alien. There was one boy named Bounce, Willie Bounce, and people thought that was funny but not funny in the same way that Petronski was.

Wanda didn’t have any friends. She came to school alone and went home alone. She always wore a faded blue dress that didn’t hang right. It was clean, but it looked as though it had never been ironed properly. She didn’t have any friends, but a lot of girls talked to her. They waited for her under the maple trees on the corner of Oliver Street. Or they surrounded her in the school yard as she stood watching some little girls play hopscotch on the worn hard ground.

‘Wanda, Peggy would say in a most courteous manner, as though she were talking to Miss Mason or to the principal perhaps. “Wanda,” she’d say, giving one of her friends a nudge, “tell us. How many dresses did you say you had hanging up in your closet?”

“A hundred,” said Wanda.

“A hundred!” exclaimed all the girls incredulously, and the little girls would stop playing hopscotch and listen.

“Yeah, a hundred, all lined up,” said Wanda. Then her thin lips drew together in silence.

“What are they like? All silk, I bet,” said Peggy.

“Yeah, all silk, all colors.”

“Velvet too?”

“Yeah, velvet too. A hundred dresses,” repeated Wanda stolidly. “All lined up m my closet.”

Then they’d let her go. And then before she’d gone very far, they couldn’t help bursting into shrieks and peals of laughter.

A hundred dresses! Obviously the only dress Wanda had was the blue one she wore every day. So what did she say she had a hundred for? What a story! And the girls laughed derisively, while Wanda moved over to the sunny place by the ivy-covered brick wall of the school building where she usually stood and waited for the bell to ring. But if the girls had met her at the corner of Oliver

Street, they’d carry her along with them for a way, stopping every few feet for more incredulous questions. And it wasn’t always dresses they talked about. Sometimes it was hats, or coats, or even shoes.

“How many shoes did you say you had?”

“Sixty.”

“Sixty! Sixty pairs or sixty shoes?”

“Sixty pairs. All lined up in my closet.”

“Yesterday you said fifty.”

“Now I got sixty.

Cries of exaggerated politeness greeted this.

“All alike?” said the girls.

“Oh, no. Every pair is different. All colors. All lined up.” And Wanda would shift her eyes quickly from Peggy to a distant spot, as though she were looking far ahead, looking but not seeing anything. Then the outer fringe of the crowd of girls would break away gradually, laughing, and little by little, in pairs, the group would disperse. Peggy, who had thought up this game, and Maddie, her inseparable friend, were always the last to leave. And finally Wanda would move up the street, her eyes dull and her mouth closed tight, hitching her left shoulder every now and then in the funny way she had, finishing the walk to school alone. Peggy was not really cruel. She protected small children from bullies. And she cried for hours if she saw an animal mistreated. If anybody had said to her, “Don’t you think that is a cruel way to treat Wanda?” she would have been very surprised. Cruel? What did the girl want to go and say she had a hundred dresses for? Anybody could tell that was a lie. Why did she want to lie? And she wasn’t just an ordinary person, else why would she have a name like that?

Anyway, they never made her cry.

As for Maddie, this business of asking Wanda every day how many dresses and how many hats and how many this and that she had was bothering her. Maddie was poor herself. She usually wore somebody’s hand-me-down clothes. Thank goodness, she didn’t live up on Boggins Heights or have a funny name. And her forehead didn’t shine the way Wanda’s round one did. What did she use on it? Sapolio? That’s what all the girls wanted to know. Sometimes when Peggy was asking Wanda those questions in that mock polite voice, Maddie felt embarrassed and studied the marbles in the palm of her hand, rolling them around and saying nothing herself. Not that she felt sorry for Wanda exactly. She would never have paid any attention to Wanda if Peggy hadn’t in vented the dresses game. But suppose Peggy and all the others started in on her next! She wasn’t as poor as Wanda perhaps, but she was poor. Of course she would have more sense than to say a hundred dresses. Still she would not like them to begin on her. Not at all! Oh, dear! She did wish Peggy would stop teasing Wanda Petronski.

SOMEHOW Maddie could not buckle down to work.

She sharpened her pencil, turning it around carefully in the little red sharpener, letting the shavings fall in a neat heap on a piece of scrap paper, and trying not to get any of the dust from the lead on her clean arithmetic paper. A slight frown puckered her forehead. In the first place she didn’t like being late to school. And in the second place she kept thinking about Wanda. Somehow Wanda’s desk, though empty, seemed to be the only thing she saw when she looked over to that side of the room.

How had the hundred dresses game begun in the first place, she asked herself impatiently. It was hard to remember the time when they hadn’t played that game with Wanda; hard to think all the way back from now, when the hundred dresses was like the daily dozen, to then, when everything seemed much nicer. Oh, yes. She remembered. It had begun that day when Cecile first wore her new red dress. Suddenly the whole scene flashed swiftly and vividly before Maddie’s eyes.

It was a bright blue day in September. No, it must have been October, because when she and Peggy were coming to school, arms around each other and singing, Peggy had said, “You know what? This must be the kind of day they mean when they say, ‘October’s bright blue weather.’”

Maddie remembered that because afterwards it didn’t seem like bright blue weather any more, although the weather had not changed in the slightest.

As they turned from shady Oliver Street into Maple, they both blinked. For now the morning sun shone straight in their eyes. Besides that, bright flashes of color came from a group of a half-dozen or more girls across the street. Their sweaters and jackets and dresses, blues and golds and reds, and one crimson one in particular,caught the sun’s rays like bright pieces of glass.

A crisp, fresh wind was blowing, swishing their skirts and blowing their hair in their eyes. The girls were all exclaiming and shouting and each one was trying to talk louder than the others. Maddie and Peggy joined the group, and the laughing, and the talking.

“Hi, Peg! Hi, Maddie!” they were greeted warmly. “Look at Cecile!”

What they were all exclaiming about was the dress that Cecile had on—a crimson dress with cap and socks to match. It was a bright new dress and very pretty. Everyone was admiring it and admiring Cecile. For long, slender Cecile was a toe-dancer and wore fancier clothes than most of them. And she had her black satin bag with her precious white satin ballet slippers slung over her shoulders. Today was the day for her dancing lesson. Maddie sat down on the granite curbstone to tie her shoelaces. She listened happily to what they were saying. They all seemed especially jolly today, probably because it was such a bright day. Everything sparkled. Way down at the end of the street the sun shimmered and turned to silver the blue water of the bay. Maddie picked up a piece of broken mirror and flashed a small circle of light edged with rainbow colors onto the houses, the trees, and the top of the telegraph pole.

And it was then that Wanda had come along with her brother fake.

They didn’t often come to school together. Jake had to get to school very early because he helped old Mr. Heany, the school janitor, with the furnace, or raking up the dry leaves, or other odd jobs before school opened. Today he must be late.

Even Wanda looked pretty in this sunshine, and her pale blue dress looked like a piece of the sky in summer; -and that old gray toboggan cap she wore—it must he something Jake had found—looked almost jaunty. Mad-die watched them absent-mindedly as she flashed her piece of broken mirror here and there. And only absent-mindedly she noticed Wanda stop short when they reached the crowd of laughing and shouting girls.

“Come on,” Maddie heard Jake say. “I gotta hurry. I gotta get the doors open and ring the bell.”

“You go the rest of the way,” said Wanda. “I want to stay here.”

Jake shrugged and went on up Maple Street. Wanda slowly approached the group of girls. With each step forward, before she put her foot down she seemed to hesitate for a long, long time. She approached the group as a timid animal might, ready to run if anything alarmed it.

Even so, Wanda’s mouth was twisted into the vaguest suggestion of a smile. She must feel happy too because everybody must feel happy on such a day.

As Wanda joined the outside fringe of girls, Maddie stood up too and went over close to Peggy to get a good look at Cecile’s new dress herself. She forgot about Wanda, and more girls kept coming up, enlarging the group and all exclaiming about Cecile’s new dress.

“Isn’t it lovely!” said one.

“Yeah, I have a new blue dress, but it’s not as pretty as that,” said another.

“My mother just bought me a plaid, one of the Stuart plaids.”

“I got a new dress for dancing school.”

“I’m gonna make my mother get me one just like Cecile’s.”

Everyone was talking to everybody else. Nobody said anything to Wanda, but there she was a part of the crowd. The girls closed in a tighter circle around Cecile, still talking all at once and admiring her, and Wanda was somehow enveloped m the group. Nobody talked to Wanda, but nobody even thought about her being there. Maybe, thought Maddie, remembering what had happened next, maybe she figured all she’d have to do was say something and she’d really be one of the girls. And this would be an easy thing to do because all they were doing was talking about dresses.

Maddie was standing next to Peggy. Wanda was standing next to Peggy on the other side. All of a sudden, Wanda impulsively touched Peggy’s arm and said something. Her light blue eyes were shining and she looked excited like the rest of the girls.

“What?” asked Peggy. For Wanda had spoken very softly.

Wanda hesitated a moment and then she repeated her words firmly.

“I got a hundred dresses home.”

“That’s what I thought you said. A hundred dresses. A hundred!” Peggy s voice raised itself higher and higher.

“Hey, kids!” she yelled. “This girl’s got a hundred dresses.”

Silence greeted this, and the crowd which had centered around Cecile and her new finery now centered curiously around Wanda and Peggy. The girls eyed Wanda, first incredulously, then suspiciously.

“A hundred dresses?” they said. “Nobody could have a hundred dresses.”

“I have though.”

“Wanda has a hundred dresses.”

“Where are they then?”

“In my closet.”

“Oh, you don’t wear them to school.”

“No. For parties.”

“Oh, you mean you don’t have any everyday dresses.”

“Yes, I have all kinds of dresses.”

“Why don’t you wear them to school?”

For a moment Wanda was silent to this. Her lips drew together. Then she repeated stolidly as though it were a lesson learned in school, “A hundred of them. All lined up m my closet.

“Oh, I see,” said Peggy, talking like a grown-up person. “The child has a hundred dresses, but she wouldn’t wear them to school. Perhaps she’s worried of getting ink or chalk on them.”

With this everybody fell to laughing and talking at once. Wanda looked stolidly at them, pursing her lips together, wrinkling her forehead up so that the gray toboggan slipped way down on her brow. Suddenly from down the street the school gong rang its first warning.

“Oh, come on, hurry,” said Maddie, relieved. “We’ll be late.”

“Good-by, Wanda,” said Peggy. “Your hundred dresses sound bee-you-tiful.”

More shouts of laughter greeted this, and oil the girls ran, laughing and talking and forgetting Wanda and her hundred dresses. Forgetting until tomorrow and the next day and the next, when Peggy, seeing her coming to school, would remember and ask her about the hundred dresses. For now Peggy seemed to think a day was lost if she had not had some fun with Wanda, winning the approving laughter of the girls.

Yes, that was the way it had all begun, the game of the hundred dresses. It all happened so suddenly and unexpectedly, with everybody falling right in, that even if you felt uncomfortable as Maddie had there wasn’t anything you could do about it. Maddie wagged her head up and down. Yes, she repeated to herself that was the way it began, that day, that bright blue day.

And she wrapped up her shavings and went to the front of the room to empty them in the teacher’s basket.