The Hungry

Authors: Steve Hockensmith,Steven Booth,Harry Shannon,Joe McKinney

Tags: #Horror, #Genre Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Literature & Fiction

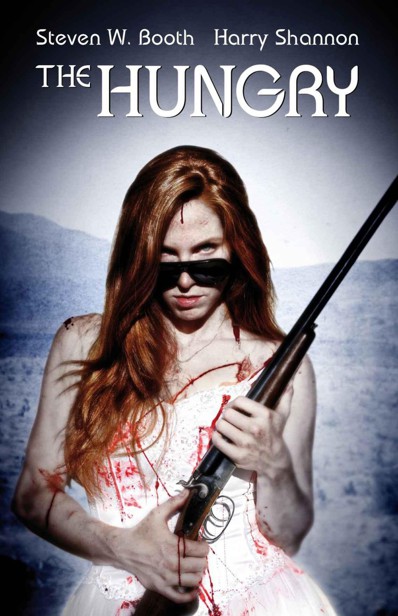

THE HUNGRY

A Novel of the Inevitable Zombie Apocalypse

Steven W. Booth and Harry Shannon

The Hungry © 2011, 2012 Steven W. Booth and Harry Shannon

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the authors' imaginations, or, if real, used fictitiously. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the author or publisher, except where permitted by law.

All Rights Reserved.

Genius Publishing

PO Box 17752

Encino, CA 91416

http://www.GeniusBookPublishing.com

https://www.facebook.com/GeniusBooks

https://www.twitter.com/#!/GeniusBooks

Cover Art: © 2011 Yossi Sasson and Dotan Bahat

Cover Model: Gillian Shure

Sherriff Penny Miller on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/TheHungryNovel

And on Twitter:

https://www.twitter.com/#!/The_Hungry

Table of Contents

The Apotheosis of Penny Miller

Coming Soon from Genius Publishing

Dedication

For my niece, Cathy, whose unbridled love of zombies defies all logic.

—S.W.B.

For my daughter, Paige, who's got her dad's taste for the macbre.

—H.S.

The Apotheosis of Penny Miller

By Joe McKinney

A few years ago I co-edited a charity zombie anthology called

Dead Set

. It was my first experience as editor, but the slim little volume that emerged from that freshman effort was actually pretty damn good.

From time to time I take a copy of it down from my bookshelf and read a little. And you know what? I still think it's pretty damn good.

But then, in all fairness, I did have it pretty easy.

A lot of great writers sent me a lot of great stories. More than I could use, in fact. Editors like having such an embarrassment of riches, even if it means rejecting the occasionally well told tale, as I was forced to do a number of times for

Dead Set

.

However, there was never any doubt about a little gem sent in by Steven W. Booth and Harry Shannon called "Jailbreak." I still remember what was going through my head the first time I read it. I had just rejected eight stories in a row, and I was starting to get a little nervous that I wasn't going to get anything that came up to my expectations.

Then, "Jailbreak."

What does that title call to mind for you? Big federal penitentiary in the middle of a zombie outbreak? Endless screaming echoing down a concrete corridor? Maybe a lone prisoner struggling against impossible odds to make a daring getaway from a zombie horde?

Wrong on all counts.

What I got instead was a tale of a small town lady sheriff named Penny Miller who is forced to join up with a deadly biker man named Scratch in order to survive the first night of a zombie apocalypse.

I read the story in one delirious burst of enthusiasm.

And from the opening line, I loved it. I loved how complete it felt. It had so many great elements working for it—the small town setting; the two powerful main characters, as different as they could be, nearly every word between them charged with sexual tension; the satisfying stalemate as neither one gets exactly what they want, but rather what they need. Booth and Shannon brought those different elements together in a seamless whole that progressed with the irresistible momentum of an avalanche. It was a great story, and for a zombie fan like me, it pressed all the right buttons.

So when I heard that the authors were expanding the story into a novel, I was thrilled.

At least at first.

Because, you see, the more I thought about "Jailbreak," the more I thought about its sense of completeness, its sense of internal unity and perfectly paced tension. How could they possibly expand that story into a novel?

And more importantly, were they going to screw it up?

Well, there's good news in zombieland folks, because they didn't screw it up. Quite the opposite, in fact. They hit a homerun. Really knocked the cover off the ball.

All of which begs the question: How did they do it?

Well, the answer's twofold. First—and this is rather obvious, but bears telling—they had to expand the plot. A short story can get away with a cozy one cell jail and a cast of two, but a novel usually requires a little more. They had to get out of the small jail, really open up the stage, so to speak. They needed constantly escalating tension, the fate of the entire world in the balance. This was, after all, supposed to be a novel of the zombie apocalypse. Apocalypse usually implies something big is going on.

But plot alone can't make a short story into a novel. The real emphasis has to be on character. That's where you get the money shot.

And for that, Penny Miller is your girl.

Let me explain.

Women do the lion's share of reading these days—at least if the surveys in

Cosmopolitan

are to be believed. And women, if you'll forgive my stereotyping, usually enjoy reading about strong female characters. They find it easy to identify with cool chicks doing cool things. I suspect that's why the recent spate of tramp stamp-wearing, Buffy-inspired Anita Blakes do so well commercially. However—and again, forgive my stereotyping—the same women reading Kelley Armstrong and Laurel K. Hamilton and Jeanne Stein probably find it slightly more difficult to identify with the testosterone-laced stories of Special Forces daring-do so popular in the old Mack Bolen novels. You will rarely find a woman reading a book on the SEALS, for instance, or the history of Vietnam's tunnel rats… unless of course it's an exercise in curiosity, a chance to see what convinced the man in her life to pick up a book for the first time in a decade.

But there's another side to Penny, and this is a little something for the gents. You see, she's a babe! She's tough. She's sexy. She's smart. And, most importantly, she knows the right way to hold a gun.

Plus, remember that Penny spends a good part of this novel running around in a wedding dress with no underwear underneath. There's something inherently sexy about a woman in a wedding dress holding a great big gun. Know what I mean? And when that same woman in the same wedding dress is willing to get down and dirty, as Penny most certainly does, you have the perfect storm of sex appeal. Find me a guy that can read a paragraph about a woman like that and then put the book down and I will show you a man without a pulse. Period.

All of which makes Penny a great choice to play the

The Hungry's

lead role. The ladies want to be her, the guys want to do her. From a strictly commercial standpoint, she's solid gold. For the movie version, I'm casting Michelle Pfeiffer.

But there's more to Penny Miller than a figurative virgin gripping a really big gun. There has to be, for if she was nothing more than a sexy caricature of an action hero, she'd be nothing but another horror trope… like the nearly interchangeable 'Final Girls' found in all those slasher flicks from the '70s and '80s. And Steven and Harry wouldn't be the authors I know them to be.

So Penny is more than flash and sex. She becomes more than that.

And it's in the becoming that Penny rises above trope status.

I've come to realize through my reading that horror—American horror, at any rate—has always been a pretty good barometer of what we think of ourselves as Americans. Consider the tales of Washington Irving, for example. "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and "Rip Van Winkle" were both written around the time of the Revolutionary War, and both stories struggle to define what it means to be an American, an issue closely mirroring the crisis of identity with which our fledgling country was struggling. This is no mere accident. And Irving is but the first in a long line of American horror writers asking the key questions about what it means to be an American.

Consider Hawthorne and his quest to come to terms with the conflicted moral landscape of our Puritan past, and the moral implications of that past on our future.

Consider Poe, whose fragile, intellectual characters suffered a crazed sort of malaise that put them in direct opposition to the smug, exuberant, ever-expanding America of the antebellum period.

Consider Jack London and his tales of life and death set against the backdrop of the conflict between Individualism and Socialism.

Or Lovecraft, who carried not only the burden of a lengthy intellectual tradition, but also the capacity to dream of a depthless reality beyond the stars, like a curse as real as any Hawthorne could have dreamt.

Or Fritz Leiber and the other masters of the '40s- and '50s-era pulps, who wrote of the terror of urbanization.

Or Stephen King, writing of the horror of life in a dying small town on the forgotten fringes of America.

Horror fiction is the mirror of our society, and its past and present masters are poets of our continual struggle to understand ourselves. Our current fascination with apocalyptic and zombie-oriented stories is certainly part of this dialogue. You have to wonder, with so many shambling, voracious hordes of the living dead advancing through today's short stories and novels, if the writers of such tales aren't making statements about how scary life is in our modern times. We are faced with dwindling resources. Our pursuit of happiness is bogged down by debt and mounting responsibilities. Our cities are overrun with inexplicable mob violence. And daily, the news shows us crimes of such savage, vacant-minded rage that one has to wonder if the real zombie apocalypse isn't right around the corner.

Or maybe it's already begun.

And on that note… enter Penny Miller.

Penny brings something new to the game, something that, I suspect, we've all been craving. Traditional horror has always been about isolation. If you want to scare audiences, you have to first isolate and alienate your main characters. Your audience will identify readily enough with a strong viewpoint character. Then, when you change the familiar to the bizarre, the comfortable to the claustrophobic, when you intrude the extraordinary into the ordinary world, you make your audience feel the fear your characters are living. Change is the key. You have to change gears on your readers in order to make them feel.

But these days we've added something new to the formula, and the name of the game is survival horror. We still create horror the old fashioned way, by isolating characters, by taking away their security blanket so to speak, but these days, we let them fight back. We take up arms against a sea of troubles, and hopefully, by opposing, end them.

That's the idea, anyway.

Critics of survival horror are fond of pointing out the pointlessness of this opposition, though. Invariably, they say, stories in this ilk—and especially zombie stories—rely on a cycle of attack, fighting back, lull, and another attack. And another and another and so on, until the reader grows numb every time another shambling figure starts to moan in the darkness.

But I think such criticisms miss the point. I listen to the news and read the papers and read some of the more political posts on Facebook, and I sense that Americans are suffering from a sort of double-barreled plague of ennui and frustration. Survival horror seems to be making a commentary on that state of mind. It is, for me, an inherently positive affirmation of an unconstrained view of human nature that challenges our tiredness and unease. Penny fights tooth and nail against those worming symptoms of hopelessness, and I can't help but wonder if there isn't something uniquely American about her as a result. What is more American, after all, than fighting back? And what is more necessary now, as we question whether America will retain her status at the top of the international food chain, than a red-blooded American girl ready to go toe to toe with the forces threatening to drag her down? She is uniquely modern, but imbued with good old fashioned values, and in my book, that makes her the perfect metaphor for a confused, frightened, but ultimately resilient America.

So, to me,

The Hungry

is ultimately an optimistic book. Your mileage may vary of course, but that's the beauty of what Steven and Harry have written. As in the best of fiction, there are no easy answers. Nobody is right, and nobody is exactly wrong either. (Sort of sounds like our current political climate to me… but I digress.) The short of it is that this book is a reflection of where we're at right now, as a nation, as a people. Penny Miller is a mirror for the reader, and becoming that mirror is her true apotheosis. What will she tell you about yourself, and about what you think it means to be an American?