The I Ching or Book of Changes (8 page)

As this example shows, all of the lines of a hexagram do not necessarily change; it depends entirely on the character of a given line. A line whose nature is positive, with an increasing dynamism, turns into its opposite, a negative line, whereas a positive line of lesser strength remains unchanged. The same principle holds for the negative lines.

More definite information about those lines which are to be considered so strongly charged with positive or negative energy that they move, is given in book II in the

Great Commentary

(pt. I,

chap. IX

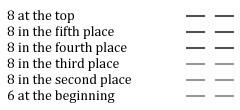

), and in the special section on the use of the oracle at the end of book III. Suffice it to say here that positive lines that move are designated by the number 9, and negative lines that move by the number 6, while non-moving lines, which serve only as structural matter in the hexagram, without intrinsic meaning of their own, are represented by the number 7 (positive) or the number 8 (negative). Thus, when the text reads, “Nine at the beginning means…” this is the equivalent of saying: “When the positive line in the first place is represented by the number 9, it has the following meaning….” If, on the other hand, the line is represented by the number 7, it is disregarded in interpreting the oracle. The same principle holds for lines represented by the numbers 6 and 8

8

respectively.

We may obtain the hexagram named in the example above —K’un, THE RECEPTIVE—in the following form:

Hence the five upper lines are not taken into account; only the 6 at the beginning has an independent meaning, and by its transformation into its opposite, the situation K’un, THE RECEPTIVE,

becomes the situation Fu, RETURN:

In this way we have a series of situations symbolically expressed by lines, and through the movement of these lines the situations can change one into another. On the other hand, such change does not necessarily occur, for when a hexagram is made up of lines represented by the numbers 7 and 8 only, there is no movement within it, and only its aspect as a whole is taken into consideration.

In addition to the law of change and to the images of the states of change as given in the sixty-four hexagrams, another factor to be considered is the course of action. Each situation demands the action proper to it. In every situation, there is a right and a wrong course of action. Obviously, the right course brings good fortune and the wrong course brings misfortune. Which, then, is the right course in any given case? This question was the decisive factor. As a result, the

I Ching

was lifted above the level of an ordinary book of soothsaying. If a fortune teller on reading the cards tells her client that she will receive a letter with money from America in a week, there is nothing for the woman to do but wait until the letter comes—or does not come. In this case what is foretold is fate, quite independent of what the individual may do or not do. For this reason fortune telling lacks moral significance. When it happened for the first time in China that someone, on being told the auguries for the future, did not let the matter rest there but asked, “What am I to do?” the book of divination had to become a book of wisdom.

It was reserved for King Wên, who lived about 1150 B.C., and his son, the Duke of Chou, to bring about this change. They endowed the hitherto mute hexagrams and lines, from which the future had to be divined as an individual matter in each case, with definite counsels for correct conduct. Thus the individual came to share in shaping fate. For his actions intervened as determining factors in world events, the more decisively so, the earlier he was able with the aid of the Book of Changes to recognize situations in their germinal phases. The germinal phase is the crux. As long as things are in their beginnings they can be controlled, but once they have grown to their full consequences they acquire a power so overwhelming that man stands impotent before them. Thus the Book of Changes became a book of divination of a very special kind.

The hexagrams and lines in their movements and changes mysteriously reproduced the movements and changes of the macrocosm. By the use of yarrow stalks,

9

one could attain a point of vantage from which it was possible to survey the condition of things. Given this perspective, the words of the oracle would indicate what should be done to meet the need of the time.

The only thing about all this that seems strange to our modern sense is the method of learning the nature of a situation through the manipulation of yarrow stalks. This procedure was regarded as mysterious, however, simply in the sense that the manipulation of the yarrow stalks makes it possible for the unconscious in man to become active. All individuals are not equally fitted to consult the oracle. It requires a clear and tranquil mind, receptive to the cosmic influences hidden in the humble divining stalks. As products of the vegetable kingdom, these were considered to be related to the sources of life. The stalks were derived from sacred plants.

The Book of Wisdom

Of far greater significance than the use of the Book of Changes as an oracle is its other use, namely, as a book of wisdom. Lao-tse

10

knew this book, and some of his profoundest aphorisms were inspired by it. Indeed, his whole thought is permeated with its teachings. Confucius

11

too knew the Book of Changes and devoted himself to reflection upon it. He probably wrote down some of his interpretative comments and imparted others to his pupils in oral teaching. The Book of Changes as edited and annotated by Confucius is the version that has come down to our time.

If we inquire as to the philosophy that pervades the book, we can confine ourselves to a few basically important concepts. The underlying idea of the whole is the idea of change. It is

related in the Analects

12

that Confucius, standing by a river, said: “Everything flows on and on like this river, without pause, day and night.” This expresses the idea of change. He who has perceived the meaning of change fixes his attention no longer on transitory individual things but on the immutable, eternal law at work in all change. This law is the tao

13

of Lao-tse, the course of things, the principle of the one in the many. That it may become manifest, a decision, a postulate, is necessary. This fundamental postulate is the “great primal beginning” of all that exists,

t’ai chi

—in its original meaning, the “ridgepole.” Later Chinese philosophers devoted much thought to this idea of a primal beginning. A still earlier beginning,

wu chi

, was represented by the symbol of a circle. Under this conception,

t’ai chi

was represented by the circle divided into the light and the dark, yang and yin, .

.

14

This symbol has also played a significant part in India and Europe. However, speculations of a gnostic-dualistic character are foreign to the original thought of the

I Ching

; what it posits is simply the ridgepole, the line. With this line, which in itself represents oneness, duality comes into the world, for the line at the same time posits an above and a below, a right and left, front and back—in a word, the world of the opposites.

These opposites became known under the names yin and yang and created a great stir, especially in the transition period between the Ch’in and Han dynasties, in the centuries just before our era, when there was an entire school of yin-yang doctrine. At that time, the Book of Changes was much in use as a book of magic, and people read into the text all sorts of things not originally there. This doctrine of yin and yang, of the female and the male as primal principles, has naturally also attracted much attention among foreign students of Chinese thought. Following the usual bent, some of these have predicated in it a primitive phallic symbolism, with all the accompanying connotations.

To the disappointment of such discoverers it must be said that there is nothing to indicate this in the original meaning of the words yin and yang. In its primary meaning yin is “the cloudy,” “the overcast,” and yang means actually “banners waving in the sun,”

15

that is, something “shone upon,” or bright. By transference the two concepts were applied to the light and dark sides of a mountain or of a river. In the case of a mountain the southern is the bright side and the northern the dark side, while in the case of a river seen from above, it is the northern side that is bright (yang), because it reflects the light, and the southern side that is in shadow (yin). Thence the two expressions were carried over into the Book of Changes and applied to the two alternating primal states of being. It should be pointed out, however, that the terms yin and yang do not occur in this derived sense either in the actual text of the book or in the oldest commentaries. Their first occurrence is in the

Great Commentary

, which already shows Taoistic influence in some parts. In the Commentary on the Decision the terms used for the opposites are “the firm” and “the yielding,” not yang and yin.

However, no matter what names are applied to these forces it is certain that the world of being arises out of their change and interplay. Thus change is conceived of partly as the continuous transformation of the one force into the other and partly as a cycle of complexes of phenomena, in themselves connected, such as day and night, summer and winter. Change is not meaningless—if it were, there could be no knowledge of it—but subject to the universal law, tao.

The second theme fundamental to the Book of Changes is its theory of ideas. The eight trigrams are images not so much

of objects as of states of change. This view is associated with the concept expressed in the teachings of Lao-tse, as also in those of Confucius, that every event in the visible world is the effect of an “image,” that is, of an idea in the unseen world. Accordingly, everything that happens on earth is only a reproduction, as it were, of an event in a world beyond our sense perception; as regards its occurrence in time, it is later than the suprasensible event. The holy men and sages, who are in contact with those higher spheres, have access to these ideas through direct intuition and are therefore able to intervene decisively in events in the world. Thus man is linked with heaven, the suprasensible world of ideas, and with earth, the material world of visible things, to form with these a trinity of the primal powers.