The Iceman Cometh (2 page)

Authors: Eugene O'Neill,Harold Bloom

A comparison of O’Neill to Beckett is hardly fair, since Beckett is infinitely the better artist, subtler mind, and finer stylist. Beckett writes apocalyptic farce, or tragicomedy raised to its greatest eminence. O’Neill doggedly tells his one story and one story only, and his story turns out to be himself.

The Iceman Cometh

, being O’Neill at his most characteristic, raises the vexed question of whether and just how dramatic value can survive a paucity of eloquence, too much commonplace religiosity, and a thorough lack of understanding of the perverse complexities of human nature. Plainly

Iceman

does survive, and so does

Long Day’s Journey

. They stage remarkably, and hold me in the audience, though they give neither aesthetic pleasure nor spiritually memorable pain when I reread them in the study.

For sheer bad writing, O’Neill’s only rival among significant American authors is Theodore Dreiser, whose

Sister Carrie

and

An American Tragedy

demonstrate a similar ability to evade the consequences of rhetorical failure. Dreiser has some dramatic effectiveness, but his peculiar strength appears to be mythic. O’Neill, unquestionably a dramatist of genius, fails also on the mythic level; his anger against God, or the absence of God, remains petulant and personal, and his attempt to universalize that anger by turning it against his country’s failure to achieve spiritual reality is simply misguided. No country, by definition, achieves anything spiritual anyway. We live and die, in the spirit, in solitude, and the true strength of

Iceman

is its intense dramatic exemplification of that somber reality.

Whether the confessional impulse in O’Neill’s later plays ensued from Catholic

praxis

is beyond my surmise, though John Henry Raleigh and other critics have urged this view. I suspect that here too the influence of the non-Catholic Strindberg was decisive. A harsh expressionism dominates

Iceman

and

Long Day’s Journey

, where the terrible confessions are not made to priestly surrogates but to fellow sinners, and with no hopes of absolution. Confession becomes another station on the way to death, whether by suicide, or by alcohol, or by other modes of slow decay.

Iceman’s

strength is in three of its figures: Hickman (Hickey), Slade, and Parritt, of whom only Slade is due to survive, though in a minimal sense. Hickey, who preaches nihilism, is a desperate self-deceiver and so a deceiver of others, in his self-appointed role as evangelist of the abyss. Slade, evasive and solipsistic, works his way to a more authentic nihilism than Hickey’s. Poor Parritt, young and self-haunted, cannot achieve the sense of nothingness that would save him from Puritanical self-condemnation.

Life, in

Iceman

, is what it is in Schopenhauer: illusion. Hickey, once a great sustainer of illusions, arrives in the company of “the Iceman of Death,” hardly the “sane and sacred death” of Whitman, but insane and impious death, our death. One feels the refracted influence of Ibsen in Hickey’s twisted deidealizings, but Hickey is an Ibsen protagonist in the last ditch. He does not destroy others in his quest to destroy illusions, but only himself. His judgments of Harry

HOPE’s

patrons are intended not to liberate them but to teach his old friends to accept and live with failure. Yet Hickey, though pragmatically wrong, means only to have done good. In an understanding strangely akin to Wordsworth’s in the sublime

Tale of Margaret

(

The Ruined Cottage)

, Hickey sees that we are destroyed by vain hope more inexorably than by the anguish of total despair. And that is where I would locate the authentic mode of tragedy in

Iceman

. It is Hickey’s tragedy, rather than Slade’s (O’Neill’s), because Hickey is slain between right and right, as in the Hegelian theory of tragedy. To deprive the derelicts of hope is right, and to sustain them in their illusory “pipe dreams” is right also.

Caught between right and right, Hickey passes into phantasmagoria, and in that compulsive condition he makes the ghastly confession that he murdered his unhappy, dreadfully saintly wife. His motive, he asserts perversely, was love, but here too he is caught between antitheses, and we are not able to interpret with certainty whether he was more moved by love or hatred:

HICKEY

Simply

.

So I killed her.

There is a moment of dead silence. Even the detectives are caught in it and stand motionless

.

PARRITT

Suddenly gives up and relaxes limply in his chair

—

in a low voice in which there is a strange exhausted relief

.

I may as well confess, Larry. There’s no use lying any more. You know, anyway. I didn’t give a damn about the money. It was because I hated her.

HICKEY

Obliviously

.

And then I saw I’d always known that was the only possible way to give her peace and free her from the misery of loving me. I saw it meant peace for me, too, knowing she was at peace. I felt as though a ton of guilt was lifted off my mind. I remember I stood by the bed and suddenly I had to laugh. I couldn’t help it, and I knew Evelyn would forgive me. I remember I heard myself speaking to her, as if it was something I’d always wanted to say: “Well, you know what you can do with your pipe dream now, you damned bitch!”

He stops with a horrified start, as if shocked out of a nightmare, as if he couldn’t believe he heard what he had just said. He stammers

. No! I never—!

PARRITT

To

LARRY

—

sneeringly

.

Yes, that’s it! Her and the damned old Movement pipe dream! Eh, Larry?

HICKEY

Bursts into frantic denial

.

No! That’s a lie! I never said—! Good God, I couldn’t have said that!

If I did, I’d gone insane! Why, I loved Evelyn better than anything in life!

He appeals brokenly to the crowd

.

Boys, you’re all my old pals! You’ve known old Hickey for years! You know I’d never—

His eyes fix

on

HOPE

.

You’ve known me longer than anyone, Harry. You know I must have been insane, don’t you, Governor?

Rather than a demystifier, whether of self or others, Hickey is revealed as a tragic enigma, who cannot sell himself a coherent account of the horror he has accomplished. Did he slay Evelyn because of a hope—hers or his—or because of a mutual despair? He does not know, nor does O’Neill, nor do we. Nor does anyone know why Parritt betrayed his mother, the anarchist activist, and her comrades and his. Slade condemns Parritt to a suicide’s death, but without persuading us that he has uncovered the motive for so hideous a betrayal. Caught in a moral dialectic of guilt and suffering, Parritt appears to be entirely a figure of pathos, without the weird idealism that makes Hickey an interesting instance of High Romantic tragedy.

Parritt at least provokes analysis; the drama’s failure is Larry Slade, much against O’Neill’s palpable intentions, which were to move his surrogate from contemplation to action. Slade ought to end poised on the threshold of a religious meditation on the vanity of life in a world from which God is absent. But his final speech, expressing a reaction to Parritt’s suicide, is the weakest in the play:

LARRY

In a whisper of horrified pity

.

Poor devil!

A long-forgotten faith returns to him for a moment and he mumbles

.

God rest his soul in peace.

He opens his eyes

—

with a bitter self-derision

.

Ah, the damned pity—the wrong kind, as Hickey said! Be God, there’s no hope! I’ll never be a success in the grandstand—or anywhere else! Life is too much for me! I’ll be a weak fool looking with pity at the two sides of everything till the day I die!

With an intense bitter sincerity

.

May that day come soon!

He pauses startledly, surprised at himself—then with a sardonic grin

. Be God, I’m the only real convert to death Hickey made here. From the bottom of my coward’s heart I mean that now!

The momentary return of Catholicism is at variance with the despair of the death-drive here, and Slade does not understand that he has not been converted to any sense of death, at all. His only strength would be in emulating Hickey’s tragic awareness between right and right, but of course without following Hickey into violence: “I’ll be a weak fool looking with pity at the two sides of everything till the day I die!” That vision of the two sides, with compassion, is the only hope worthy of the dignity of any kind of tragic conception. O’Neill ended by exemplifying Yeats’s great apothegm: he could embody the truth, but he could not know it.

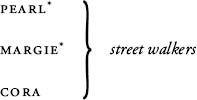

HARRY HOPE,

proprietor of a saloon and rooming house

*

ED MOSHER,

Hope’s brother-in-law, one-time circus man

*

PAT MCGLOIN,

one-time Police Lieutenant

*

WILLIE OBAN

,

a Harvard Law School alumnus

*

JOE MOTT

,

one-time proprietor of a Negro gambling house

PIET WETJOEN

(“

THE GENERAL

”),

one-time leader of a Boer commando

*

CECIL LEWIS

(“

THE CAPTAIN”),

one-time Captain of British infantry

*

JAMES CAMERON

(“

JIMMY TOMORROW

”),

one-time Boer War correspondent

*

HUGO KALMAR,

one-time editor of Anarchist periodicals

LARRY SLADE,

one-time Syndicalist-Anarchist

*

ROCKY PIOGGI

,

night bartender

*

DON PARRITT

*

CHUCK MORELLO,

day bartender

*

THEODORE HICKMAN

(

HICKEY

),

a hardware salesman

MORAN

LIEB

*

Roomers at Harry Hope’s.

Back room and a section of the bar at Harry Hope’s

—

early morning in summer, 1912

.

Back room, around midnight of the same day

.

Bar and a section of the back room

—

morning of the following day

.

Same as Act One. Back room and a section of the bar—around 1:30

A.M.

of the next day

.

Harry

HOPE’s

is a Raines-Law hotel of the period, a cheap ginmill of the five-cent whiskey, last-resort variety situated on the downtown West Side of New York. The building, owned by Hope, is a narrow five-story structure of the tenement type, the second floor a flat occupied by the proprietor. The renting of rooms on the upper floors, under the Raines-Law loopholes, makes the establishment legally a hotel and gives it the privilege of serving liquor in the back room of the bar after closing hours and on Sundays, provided a meal is served with the booze, thus making a back room legally a hotel restaurant. This food provision was generally circumvented by putting a property sandwich in the middle of each table, an old desiccated ruin of dust-laden bread and mummified ham or cheese which only the drunkest yokel from the sticks ever regarded as anything but a noisome table decoration. But at Harry Hope’s, Hope being a former minor Tammanyite and still possessing friends, this food technicality is ignored as irrelevant, except during the fleeting alarms of reform agitation. Even

HOPE’s

back room is not a separate room, but simply the rear of the barroom divided from the bar by drawing a dirty black curtain across the room.

SCENE

The back room and a section of the bar

of

HARRY HOPE’S

saloon on an early morning in summer, 1912. The right wall of the back room is a dirty black curtain which separates it from the bar. At rear, this curtain is drawn back from the wall so the bartender can get in and out. The back room is crammed with round tables and chairs placed so close together that it is a difficult squeeze to pass between them. In the middle of the rear wall is a door opening on a hallway. In the left corner, built out into the room, is the toilet with a sign

“

This is it

”

on the door. Against the middle of the left wall is a nickel-in-the-slot phonograph. Two windows, so glazed with grime one cannot see through them, are in the left wall, looking out on a backyard. The walls and ceiling once were white, but it was a long time ago, and they are now so splotched, peeled, stained and dusty that their color can best be described as dirty. The floor, with iron spittoons placed here and there, is covered with sawdust. Lighting comes from single wall brackets, two at left and two at rear

.