The Immortalist (30 page)

Authors: Scott Britz

“You listened in on Dr. Gifford?”

Loscalzo smiled teasingly. “Don't get all riled up. We had a nice, friendly meeting, the doc and me. I was sittin' here when he came out to feed his dog. See that silver bowl in the grass? That's top sirloin in there. The doc had a chef bring it out, sizzlin' in a skillet. But the dog wouldn't touch it for shit. The doc looked into the pooch's eyes and mouth and nose, like he was sick or somethin'. Whole fine-tooth comb. But jeezâtop sirloin? When I was a kid, we'd just leave the fuckin' dog in the barn until he got himself well. Or not.”

“To hell with the dog. Gifford told you Cricket Rensselaer-Wright was still on campus?”

“No. He told Niles.”

“That doesn't make sense. We moved heaven and earth to get rid of her.”

Loscalzo grinned. “Now you know why I thought you might want to have that Maputo footage. Cost me a bundle to get it, too.”

Niedermann quickly pocketed the flash drive. “Thanks. What do I owe you?”

“Forget it. This one's on me.” Loscalzo waved dismissively. “How about that other thing? Got it?”

Niedermann brought out a bulging envelope from under his jacket. “Here's fifty grand in cash. That's way more than I've been paying you.”

Loscalzo looked at the money as if it were poison. “We had a deal, friend. Goods, not cash.”

“That's not happening, Dom. There isn't any Vector stock left. Maybe when we finish a new batch next week.”

“Next week? Tell Rod Baer to wait until next week.”

“I can't do that.”

“Why the fuck not?”

“I don't dare stiff people like him. My life wouldn't be worth two cents if I tried that. He's used to getting what he wants.”

“And me? What am I used to? Takin' it up the ass?”

Niedermann said nothingâonly held out the envelope, shaking it.

“I wouldn't show that out in the open, if I were you.”

“Take it, then.” Niedermann tossed the money onto the wrought-iron table.

“No fuckin' thanks.”

“Not enough?”

Loscalzo shot up from his seat and stormed toward the edge of the patio. Eyes downcast, he fell to scuffing the tiles with his boot. “You just don't get the point, do you? It's not about me. I don't want a cent. It's for my ma, understand? I'm tryin' to do what's right for her.”

Niedermann laughed. “Have you any idea what those doses go for? A million dollars apiece. This whole wad of cash wouldn't touch it.”

Loscalzo's face went dark. “What are you laughin' at? My ma?”

“I'm laughing at you, Dom. Thinking you could shake me down over this.”

“What if I went to the FDA?”

“And told them what? That I'm holding out a few extra doses of the Methuselah Vector? Where's the evidence?” Niedermann laughed again. “They'll never find a trace. There's not even a shred of proof that you ever worked for me.”

Loscalzo's jaw muscles rippled. “Oh, you're fuckin' smart, you are.” He spit his gum out onto the lawn.

“Yes, I am. Now, if I need anything else from you, I have your number.” Niedermann had heard all the rumors about Loscalzo. Two years in federal prison for obstruction of justice. Some racketeering charges, never proved. A story about an informant in the longshoreman's local who turned up in the East River minus his head and his fingertips. There was no question that Loscalzo could be dangerous. That was exactly why Niedermann had to be tough with him. Men like that had a sixth sense for fear.

Loscalzo wandered distractedly onto the grass and tapped the bowl of sirloin with the toe of his boot, sizing it up. Then he unleashed a flying kick, as if he were returning a football from the thirty-five-yard line. Chunks of sirloin steak scattered across the grass. “All I asked for was one stinking little hypo's worth of medicine.”

“You can't have it. There's your wagesâright there.” Niedermann nodded toward the envelope on the table. Money, he knew, was the last word with Loscalzo. “Now scram. Remember, I don't just pay you to show up for work. I pay you to stay the hell out of sight, too. So get your ass back to New York before anyone starts asking questions.”

In a show of bravado, Niedermann turned his back and marched toward the house. He was relieved when, out of the corner of his eye, he saw Loscalzo slink back to the table for the money.

But Loscalzo said something under his breath as he picked it up. Something Niedermann couldn't quite make out.

Or I might just stick around

is what it sounded like.

Nine

IT WASN'T SHRIMP

SCAMPI, BUT CRICKET

was glad for the tuna wrap Erich Freiberg and Wig Waggoner had brought her. Leaving Hank and Jean to watch over Emmy, she took advantage of her first break in hours to prop her aching feet on a chair, and to replenish her own body fluids with a Diet Coke. On the other side of the office desk, Freiberg and Waggoner watched her tear hungrily into her food.

Freiberg, who had called her out of Bay 2 to hear important news, sat with his hands primly folded in his lap. “First things first. How is Emmy?”

“She's holding on. Her body is fighting back with everything it's got.”

Freiberg smiled. “Winning, I hope?”

Cricket dropped her wrap onto the desk and glared at him. “No. We're losing. She can't breathe on her own anymore. The chest X-rays are getting worse. She's bleeding internally. I've given her ten units of whole blood, but still her hematocrit keeps dropping. I . . . I just don't know what else to do.”

“Dr. Waggoner has discovered something that might help.”

Cricket's gaze shot toward Waggoner. He was staring at the floor. There was a very long pause as Cricket and Freiberg waited. Suddenly Waggoner looked up in surprise. “Is this where I come in?”

Freiberg nodded. “Come in anytime, Wig. You're the man of the hour.”

Waggoner unfolded a sheaf of papers from his lab-coat pocket. “I, uh, ran some analyses of that blood sample you gave me. A rapid PCR test, using the same primer sets as for Sample Number Oneâ”

“Sample Number One? What is that?” asked Cricket.

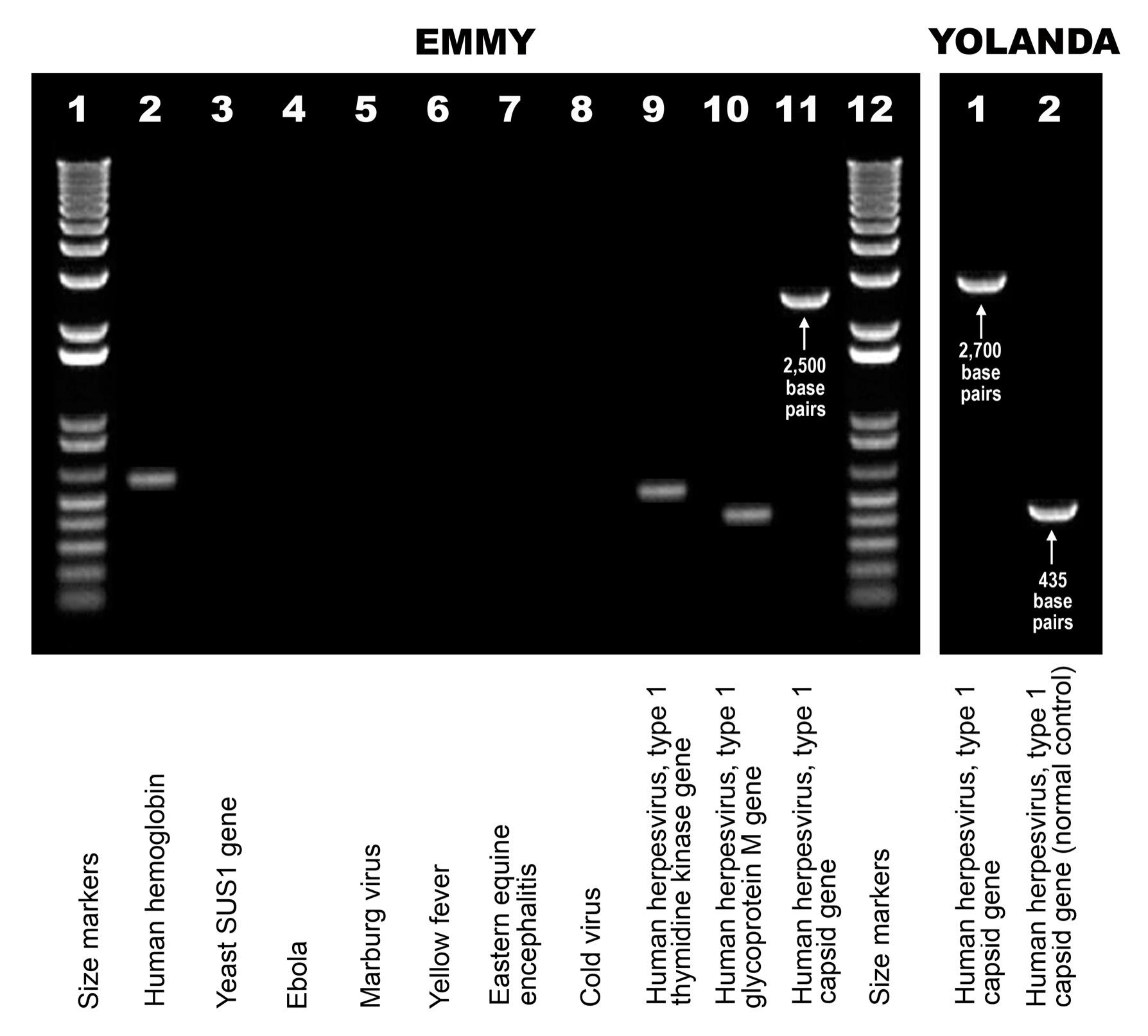

“Jack Niedermann's secretary. Yolanda Carlson,” said Waggoner, frowning at the interruption. “Here's a printout of an agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products for Sample Number Two, the new oneâyour, uh, daughter.” As he spoke, he ran his finger across a photograph of a black rectangle. Twelve vertical columns, or lanes, were spread across it. The outside lanes were marked by irregularly spaced white lines, like the rungs of a ladder. Lane two showed a single white line. The next six lanes were empty. Lanes nine, ten, and eleven on the right each showed a single white line.

Figure 1.

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) to test for the presence of viral DNA.

Lanes 1 and 12

: standard DNA size markers.

Lanes 2 and 3

: positive and negative controls to show that PCR reaction is working.

Lanes 4 through 8

: Emmy's blood is completely free of Ebola, Marburg virus, Yellow fever virus, Eastern equine encephalitis virus, and human cold virus.

Lanes 9 and 10

: fragments of expected size are seen for two genes (thymidine kinase and glycoprotein M) from Human herpesvirus, type 1; this indicates that a herpesvirus infection is present. Lane 11: reaction is also positive for the capsid protein of Human herpesvirus, type 1, however the product is abnormally long (2,500 base pairs instead of 435). A detail from Yolanda's PCR test (right side of figure) shows that her blood is also positive for capsid protein, but the product is even longer than Emmy's (2,700 base pairs).

“Give me a second here, Wig,” said Cricket, as she studied the printout. “I'm a clinical field researcher. This isn't my area. I want to be absolutely sure I understand what you're saying. You extracted and purified DNA from my daughter's blood, and then used PCRâpolymerase chain reactionâto amplify specific pieces of that DNA?”

“Yeah.”

“And the agarose gel?”

“It's like a sieve. Big molecules, like DNA PCR products, can pass through it, but there's enough resistance to slow them down. DNA has a negative electrical charge, so if we run an electric current, the PCR products will all head for the positive pole. But the bigger molecules will move slower, because of the sieve. By also running a âladder' of standard DNA pieces of known size, we can compare the speeds and estimate how long a product is.”

“And what does that tell us?”

“That we have human herpesvirus, type 1.”

“That's impossible.” Cricket shoved the printout back at him. “My daughter's symptoms are those of a highly virulent hemorrhagic virus. Not herpes.”

“You said the same thing about Yolanda Carlson.”

“It was true then, also. There's something wrong with this analysis.”

Waggoner's eyes opened wide. “The analysis is indisputable!” He pushed the printout back toward Cricket and again ran his finger back and forth over it. “As always, I carried out both positive and negative controls. Here in this lane you can seen the human hemoglobin A gene, positive exactly as it should be. The next lane is a unique intron sequence from the SUS1 gene of the yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

. That lane is empty, as it should be, since your daughter is not a yeast. This proves that the PCR reaction worked perfectly.”

“And these other lanes?”

Waggoner pointed to the lanes one by one with his forefinger. “Ebola, negative. Marburg disease, negative. Yellow fever, negative. Eastern equine encephalitis, negative. And so on. But here, three out of three lanes are positive for herpes simplex. Two of them are of the exact length predicted.”

“Two? What about the third?”

“It runs longer. It's from a capsid protein in the unique long region of the herpes simplex genome. It should run four hundred sixty-Âfive base pairs long. Instead, it's about twenty-five hundred.”

“That's a big difference.”

“It happens. There can be secondary structure in the DNAâtwisting on itselfâthat can interfere with the binding of one of the primers. In cases like that, the blocked primer sometimes finds another binding site somewhere downstream. Then you get a product of abnormal length. But it still proves that at least one of the primers found herpes simplex. It's still positive, in that sense.”

“Did Yolanda's PCR have a product of the same abnormal length?”

“Almost.”

“What do you mean, almost?”

“Yes, there was a long product. But it ran a little bit slower.”

“Slower? That means it was longer, right?”

“Yeah, by a couple hundred base pairs.”

“Wig, help me out here. Does that mean they were different viruses?”

“No. Both were human herpesvirus, type 1. But your daughter's virus is a mutant. Somehow, it lost about two hundred base pairs from the capsid region.”

“Can you explain that?”

“Viruses do that kind of thing all the time. They're really messy replicators. But what it does suggest is that your daughter didn't catch the virus from Yolanda Carlson. The mutation occurred inside of a third host. That host and Yolanda could have caught it from yet another source, but your daughter had to have come later in the chain of transmission.”

“Finally, you and I agree on something, Dr. Waggoner.”

“We do?”

“From the condition of my daughter's hand, I believed she was infected by a dog bite. Not by Yolanda.”

Waggoner jerked back his printout. “That's impossible. Dogs don't get human herpes, or vice versa.”

“But this isn't normal human herpes, is it? The capsid protein is twenty-five hundred base pairs long, not four hundred sixty-five.”

“Th-that's an artifact.”

“You don't really know that. You haven't actually sequenced the DNA of these PCR fragments, or of the virus itself, have you?”