The Importance of Being Seven (17 page)

On the morning on which Bertie took Ulysses to school, Angus Lordie followed his normal routine of an early walk with Cyril round the Drummond Place Gardens, followed by a breakfast of coffee accompanied by two croissants. Living on his own, he felt no inhibitions about reading at table, alternating between a book, which he read on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and a newspaper or magazine on the other four days of the week. The newspaper was invariably the

Scotsman

, where he turned first to

Duncan Macmillan’s art column – if it was a Macmillan day – or to Allan Massie, both of which writers he was in complete agreement with on all subjects. If it was a day for a magazine, then it would be the art review in the

Burlington Magazine

, where, in view of his impending trip to Italy, he was currently taking a particular interest in articles on Italian subjects. Thus a review of ‘Altarpieces and their Viewers in the Churches of Rome from Caravaggio to Guido Reni’ was read over a croissant and strawberry jam; and coffee, black and strong, was the perfect accompaniment to an article on newly discovered miniatures by Pacino di Bonaguida.

After breakfast, Angus Lordie went through to his studio, followed by Cyril, who usually padded after him if he moved rooms, settling himself in an accustomed spot and watching his master for any signs of dog-related activity: the fetching of a lead would be a signal for immediate enthusiastic barking; the fetching of a dog bowl would bring an immediate wagging of the tail and the protrusion, over canine canines, of a ready-to-serve tongue. But while Angus was painting, Cyril knew that as little distraction as possible was wanted; this reminded Angus of the rule in the Savile Club in London where, on the members’ breakfast table, is displayed a sign saying

Conversation Not Preferred

. He had enjoyed an absurd exchange with Domenica on the subject.

‘Such wording is so polite,’ he remarked. ‘Yet it’s unambiguous: there is no prohibition of conversation, but to initiate it would be to go against the wishes of the committee, and that should, in civic society, be enough to inhibit.’

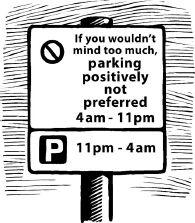

‘Oh yes,’ said Domenica. ‘But one can’t have polite requests in all situations. What about parking regulations? Do you think that people would obey polite signs that simply requested them not to park?’

Angus thought about this for a moment. ‘They might do so in Edinburgh, don’t you think? Can’t you just imagine it? We wouldn’t have signs saying No Parking, or Parking Prohibited; our signs would confine themselves to saying Parking Not Preferred. And should a driver ignore such a sign, then a traffic warden would place a small ticket on his or her windscreen. This would read:

“This is rather inconsiderate of you. Please don’t park here, if you don’t mind awfully. Thank you.” ’

Domenica stared at him. ‘Which world are you living in, Angus?’

Angus looked rueful. ‘Not this one, I suppose. But don’t you think that there’s a point in having some idea of a better world? Don’t most people have something like that?’

Domenica admitted that some did – Utopian socialists, for instance, who believed in the perfectibility of man if only we could establish economic justice and the conditions that went with that. ‘But they are so few these days,’ she said. ‘Most people now believe that the world is hopelessly flawed and that at the most we can tidy it up around the edges.’

‘And religious people?’ asked Angus. ‘Don’t most religions have an idea that the world can be made better – if only people would see the world from their point of view, which of course not everybody does.’

‘They do, I suppose,’ said Domenica. ‘And that swells the numbers of those who believe that we might have a better future. But …’

Which world am I living in?

The question haunted Angus. He was an artist and he believed that he had a vocation. He had to create – that is what he wanted to do, and he believed that the need he felt to do this was as important to him as food and drink. He could not envisage life without the ability to pick up a brush and put paint to canvas; it was not something he did because he earned his living in this way, or because it kept boredom at bay; he did it because that was the reason why he got out of bed each morning. He lived to paint.

And yet, he wondered what good this powerful urge had done either him or the world in general. Artists, like anybody else, had a social purpose, which was … what? To increase the amount of beauty in the world? If this was what artists were for, then he was, in a sense, a mere decorator. Or did the creation of beauty have a purpose beyond the deed of its creation? Beauty and truth were linked, he had always assumed, and to create beauty was to state a truth. And if one stated a truth, one was revealing that truth to others and that, surely, was worth doing for itself.

As an artist he was committed to beauty, and yet what contribution to an understanding of beauty had he made? He thought of his portrait painting. When he painted a portrait he tried to capture something about the essence of the sitter. The perception of that essence might have an uplifting effect on the person who gazed upon the painting, but that, he thought, was rare, and was possibly restricted to portraits of beautiful sitters. It did not apply, he thought, to his unfinished portrait of Ramsey Dunbarton, the retired solicitor who had been so inordinately proud of playing the part of the Duke of Plaza-Toro in

The Gondoliers

at the Churchhill Theatre. His portrait of Ramsey, not completed because of the death of the sitter – in Angus’s studio – added nothing to human understanding. All that it said was that there was once a man who looked like this, who was painted by this particular artist. It was of no greater interest, Angus told himself, than an entry in an old telephone directory. Such entries say there was once a person called this who lived at this address and who could be reached at this number.

I must do something permanent, he thought. And then he thought of Italy, and of all that it meant for our sense of beauty. I shall paint something of great significance there, he thought.

He shivered. Something was upon him – filling him with a sense of power and possibility. A great painting, he thought. At last.

Angus painted for two hours before pausing. The canvas on which he was working was an undemanding one – a group portrait commissioned by a bank of its board of directors. He had chosen to portray the directors in both standing and sitting poses, casually placed around a boardroom, with one even looking out of the window and caught only in profile. The commission had preceded the disaster that struck the bank, a few months before the howling winds of financial crisis had stripped away the clothing of centuries and exposed alarmingly shaky foundations. Angus had finished the sittings when this began, and had awaited instructions from the bank as to what to do. Several of the directors had gone: was he to paint out their faces in the way of official artists of the old Soviet Union, where discredited members of the Politburo found themselves over-painted with vases of flowers? No such instruction came from the bank, which, having agreed to pay his fee, felt obliged to honour the contract.

‘Perhaps I could paint one or two of them looking regretful,’ Angus suggested to the bank official who had made all the arrangements. ‘Would that do? It would be recording a particular moment in banking history, and might therefore be of greater interest in the future. What do you think?’

This had been greeted with silence. Then the official said, ‘I’m not sure if all of them are regretful. Some of them, certainly, but not everyone at that level seems to have donned sackcloth and ashes.’

Angus thought about this. There had been general calls for punishment and retribution, with eager

tricoteuses

taking up their station outside corporate headquarters, but this had left him feeling vaguely uncomfortable. There had been greedy bankers, but almost everybody else had been greedy too. Did those who rejoiced in the high returns on their savings stop to think that they were part of the problem, that they were

rentiers

? Did those who ran up high credit card bills stop to think that they were part of the mountain of debt that the reckless economic party was building up? Many first stones had been cast, he thought.

‘Or a

paysage moralisé

?’ asked Angus. ‘There’s a window in the picture. There could be a

paysage moralisé

outside.’

The official cleared his throat. ‘You must forgive me – that’s not a banking term.’

‘The landscape does the work,’ explained Angus. ‘One paints an allegorical landscape to make a point about life. A barren valley. High mountains presenting an obstacle to the traveller. Burning haystacks.’

‘How interesting. But somehow …’

‘No, I understand. Nothing disturbing.’

So now he stood before his easel, adding the final touches to a picture that he suspected would never be fully displayed. It was an act of piety on the part of the bank, recording the board in happier times, but its destiny would be to hang – if it were to hang at all – in some back room or corridor, away from the bright offices in which the real business of the bank was conducted. The prospect of his work being relegated in this way filled him with despair and made him all the more determined to do something that mattered. This brought his thoughts back to Italy. Italy was the solution, at least for artists. If there was any country that was the spiritual home of artists, then it was Italy, which had been succouring the artistic soul for centuries. Italy would recharge him, would provide him with the inspiration for a new phase in his work.

He put down his brush, not even bothering to wipe it or dip it in spirit; he would do that later. He looked at his watch. He could go to Big Lou’s for coffee, but somehow he wanted something fresh, something different. A walk perhaps and then … Yes, Italy … He had no clothes that would be suitable for Italy. Domenica and Antonia would be bedecked in large straw hats, no doubt, and cool blouses, whereas he had his Harris tweed and his moleskin trousers (with their paint stains), which nobody could wear in Italy.

‘Cyril,’ he said. ‘We’re going shopping.’

Cyril understood only one word of that: his name. But there was no mistaking Angus’s body language, and all dogs are expert interpreters of body language. Leaping to his feet, Cyril gave two

enthusiastic barks to indicate readiness. The lead was fetched and the two made their way downstairs.

It was a walk of some fifteen minutes to the premises of Stewart, Christie & Co on Queen Street. Inside the shop, an assistant greeted Angus and had a kind word for Cyril. Then he listened to Angus’s request: a tropical jacket – linen, preferably – and a lightweight pair of trousers. Perhaps a few shirts, too, and a Panama hat.

Cyril watched as the garments were brought to Angus for approval. He showed no interest in the jacket and the trousers, but the Panama hat engaged his attention, possibly for its evident chewability.

Angus cast an eye about the shop as his purchases were being wrapped. He noticed a tray of large coloured handkerchiefs; one, a spotted red bandanna, stood out from the rest. He looked down at Cyril, who was gazing up at him with dark, liquid eyes. How would Cyril look, he wondered, with a red bandanna around his neck? He made his decision.

Outside, Angus and Cyril began to walk back along Queen Street. The day, which had been slightly overcast to begin with, had cleared. Now the sky of high summer was empty – so empty that blue had been attenuated into a shade so pale that it was almost white. The trees in Queen Street were heavy with leaf; green luxuriance as counterpoint to the grey-and-honey tones of the buildings.

Cyril trotted beside Angus, an undoubted spring in his step, the red bandanna contrasting nicely with the dark of his coat. He feels enhanced, thought Angus; and so too might all of us be enhanced – by a touch of red, by a fine day, by being alive in this splendid city, this heart-entrancing place.

Most of us, if pressed, are made uneasy by change. We recognise its importance in our lives and there are occasions when we persuade ourselves that it is for the best – which, of course, it often is – but

at heart we are concerned that, if change comes, it will bring with it regret.

This is particularly so when it comes to those who look after us. Doctors and dentists retire or move, much as the rest of us do. This is usually much regretted by those who are their patients, who then have to get used to a new face and a new approach to the aches and afflictions to which flesh and bone is heir. And the same must be said of the disappearance of plumbers, who understand the idiosyncrasies of our U-bends and lesser drains; of mechanics, who remember our suspension as if it were their own; of postmen, who are familiar with the shed where we like our parcels to be left, or with quite the right angle at which to press our sporadically functioning doorbells.

The worst of all such changes, though, is a change of psychotherapist. The problem with this is that the narrative is interrupted; for months, perhaps years, the patient has discussed himself or herself with the psychotherapist. Now, quite suddenly, it seems that this discussion has been abandoned by one side. For the patient it must be like telling a long joke only to find, some time before the punchline, that the audience has changed and does not know what went before. Why were these three men in the balloon, may we ask? Would you mind going back to the beginning?

In psychoanalysis, the full-blown, long-drawn-out, daily unburdening that can take years, or decades to complete, the change of an analyst can be a disaster. Indeed, such is the dependence that may develop between analyst and analysand that many psychoanalysts simply cannot find it in themselves to retire, and continue to sit and listen to their patients until the very end, either for the patient or the analyst. Freudian lore is full of stories of analysts who have died of sheer old age in their psychoanalytical chair; or patients who have similarly succumbed while on the couch. The narrative falters and stops; the word-association suddenly becomes one-sided, with words hanging in the air unanswered.

This dependence, though officially discouraged in psychoanalytical circles, can be quite touching. In both Vichy and occupied France, psychoanalysis hardly flourished. There were, however, a few elderly analysts who were, on liberation, accused of

collaboration. These had little alternative but to move to Morocco, where they established themselves in Casablanca. Their patients moved too. And when these elderly psychoanalysts died, their patients arranged, in due course, to be buried alongside them. Thus did the relationship continue beyond the grave, as if the analyst lay interred for all eternity, patiently listening to all the unresolved issues emanating from the next-door plot.

Six is not an easy age at which to change one’s psychotherapist, and indeed Irene was concerned that the experience would be so traumatic for Bertie that therapeutic support would be required for the consequences. This, of course, was not the case, as Bertie, who was an entirely normal little boy, had no need of psychotherapy in the first place. But she was loath to accept that, and when Dr Hugo Fairbairn, author of

Shattered to Pieces: Ego Dissolution in a Three-Year-Old Tyrant

, went off to Aberdeen, she was concerned that his successor, Dr St Clair, would be able to pick up the strands of the complex therapeutic process to which Bertie had been introduced.

For Dr Fairbairn, the offer of a chair from the University of Aberdeen had come at an opportune time. The chair in Aberdeen was prestigious, and it would give him the opportunity to write a book that he had recently been planning,

The Psychopathology of the Over-Intrusive Mother, or Mater Dentata

. But there was more to it than that, and had his own decision been subjected to the scrutiny that he gave to decisions made by his patients, it would have been apparent that Dr Fairbairn was running away from Edinburgh because of what he had himself termed his rucksack of guilt.

This guilt came from the fact that he had, many years ago, slapped a particularly trying young patient, Wee Fraser, after Wee Fraser had, in a quite unprovoked manner, suddenly bitten him.

Many years later, with Wee Fraser now fifteen or thereabouts, Dr Fairbairn had met him on a bus to Burdiehouse; Wee Fraser, dimly remembering the psychotherapist, but not to the extent of knowing who he was or how their paths had previously crossed, had, as a precautionary measure, head-butted him. Whereupon Dr Fairbairn had struck the boy, possibly dislocating his jaw, and run away. This, in guilt terms, had piled Pelion upon Ossa, or, in Scottish

terms, Ben Nevis upon Ben Macdui. What could one do, in such circumstances, but flee? And in what direction to flee but north?

The choice of north was highly significant. Those who flee south flee to an imagined territory of forgiveness; they flee to Mother; to a place where whatever they did is no longer important; Mother forgives, she always has and always will.

Spain, Portugal, Italy – those countries where the Marian visions appear so unexpectedly in grottoes or olive groves – these are places to which those overburdened in the Protestant north go for solace or forgetfulness, to get away from the stern judgement of the north. Dr Fairbairn went north because he wished to appease reason.

He was replaced by Dr St Clair, who therefore became Bertie’s psychotherapist. He came without preconceptions and would have discharged his young patient more or less immediately, had there not been that unfortunate misunderstanding about wolves. This had made him decide to continue with treatment, and Bertie, as ever, acquiesced. What could he do?

One cannot divorce one’s mother, especially when one is only six. All one can do, really, is wait until one turns eighteen, that milestone at which adulthood and independence begin. But between six and eighteen is a gulf of years wider than an ocean, or a desert, or any of those features which, at the age of six, seem endless, seem infinite.