The Incredible Human Journey (16 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Stephen wondered if α-thalassaemia in his New Guinean patients was doing the same thing. It turned out that he’d hit the nail on the head.

1

,

2

,

3

So that explained how Stephen had become interested in genes, and medical genetics was a thoroughly respectable area of research for a clinician to engage in. But Stephen also realised that the genes he was looking at didn’t just represent the adaptations of a population to the tropical environment they now inhabited, but also acted as some sort of record of where those populations had come from: they could be used as markers of human migration.

‘What was interesting was that the various mutations causing α-thalassaemia were present in different frequencies in groups of people speaking different languages,’ explained Stephen. ‘There was a particular α-thalassaemia mutation which was specific to Austronesian-speaking coastal and island populations, and different from the mainland New Guinea variant. There seemed to be a genetic trail out to the Pacific – probably very ancient – and you could still see it in the population along the north coast of New Guinea.’

He was entering a different world – the world of archaeology and anthropology, with theories usually built on fragments of fossils and stone tools – but he was confident that the genes within modern populations held important clues that could help unravel the riddle of human origins. ‘I found it fantastically exciting that very specific genetic mutations could act as trailmarkers for ancient migrations. I haven’t really stopped thinking about it ever since, and that was twenty-five years ago.’ Although he continued to work as a clinician, Stephen had also published a huge amount of research into genetics and the dispersal of modern humans, looking in particular at mitochondrial DNA. And that is what had brought him to the Lenggong Valley rainforest. He was there to gather samples of mtDNA from a group of Orang Asli (‘original people’), who have long been presumed to be Aboriginal Malaysians.

There are many tribes of Orang Asli, divided into three main groups, of which the smallest is the Semang; this group is also thought to be the most ancient. Some sources have described them as African-looking, with very dark skin and thick black hair. The Semang, of all the Orang Asli, have also held on to their traditional way of life as hunter-gatherers the longest. The people we were going to see were one of those Semang tribes, the Lanoh. They live in the Upper Perak district, and they have another name for themselves,

Semark Belum

, which means ‘the original people of the Perak River’.

4

Stephen had already investigated mitochondrial lineages among the majority Malay population, and within other Orang Asli groups, but the DNA of the Lanoh people had never been sampled before. I was interested in the story held in their genes, but I was also looking forward to meeting some people who were still living as hunter-gatherers. Sadly, though, they are very much hunter-gatherers under threat. Writing in 1976, anthropologist Iskander Carey was able to state that the Semang were just about the only Orang Asli group to ‘practise little or no cultivation’ and that they were ‘the only true nomads’ in Malaysia. But the Lanoh tribe no longer fitted that description. Since the 1970s, the Malaysian government had taken measures to ‘resettle’ the Orang Asli, building villages where the once-nomadic tribes could be brought together to settle down and make a useful contribution to the economy. We were to meet the Lanoh in one such village at Kampong Air Bah (‘Flooding River Settlement’). For these people, who had lost not only most of their jungle, but also any rights to their former territory, hunting and gathering was now little more than a pastime. Real labour meant working on rubber plantations, farms and logging camps. Like many groups of people subsisting as hunter-gatherers on the fringes of agricultural and industrial populations, the Lanoh are in the process of being swept up and forced to leave the old ways behind. It is a story that must have happened thousands of times, over thousands of years, since the time that some people started to farm and build civilisations.

The commercial pressures that were changing the lifestyles of the ancient populations of Malaysia were also changing the ancient landscape: logging was stripping the hillsides bare, and palm oil monoculture followed in its wake. The effect was quite astounding from the air: on the flight into Kuala Lumpur I’d seen hills and valleys completely divested of green, with the bulldozer tracks forming strange ridged patterns like pink thumbprints on the land. Some were starting to grow green again, but with palm oil seedlings rather than ancient rainforest. The palm oil plantations covered vast areas, in regular patterns and standard green. On the ground, we drove through acres and acres of oil palms, durian orchards and rubber tree plantations, before we reached Kampong Air Bah, tucked inside a remaining bit of forest.

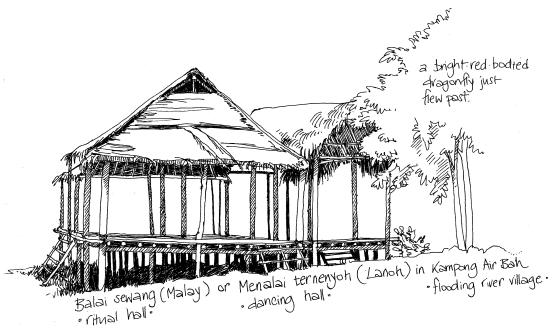

Individual houses occupied the lower ground. These were modern houses, still on stilts, but many had more traditional extensions of bamboo and woven bertam palm walls. On the higher ground was a small mosque (as the Lanoh are now nominally Muslim) and a large, wall-less wooden building with a thatched roof of palm leaves. This was the

balai sewang

(in Malaysian) or

menalai ternenyoh

(in Lanoh) – a building that served the purposes of meeting place, village hall and dance hall. It formed the physical and social centre of the Lanoh village.

We pulled up in our Land Rovers next to the

balai sewang

, removed our shoes and climbed the wooden ladders to the raised floor of the hall, where the

penghulu

(‘leader’) of the Lanoh, Alias Bin Semedang, greeted us. We were ushered in to sit crosslegged on the floor, with Alias and some other elders. After introductions, we explained why we wanted to visit the Lanoh. Stephen carefully related his search for ancient lineages and asked Alias if it would be possible to take cheek cell samples from members of the group. I asked if I could accompany the tribe, hunting and gathering in the rainforest. Alias seemed to discuss the requests with the other elders, then turned to us. Even before the translation came back to us, we knew from his smile that it was good news. I told Alias that previous studies had already shown that other Semang tribes had ancient genes, ancient blood, and their ancestors were the first in the land. Alias was unsurprised by this; in fact, he told us that the Semang were

the

original people and everyone else had come from them.

Stephen set out his stall and prepared to collect cheek cells, opening boxes of long-handled brushes that the Semang participants would rub up and down inside each cheek. (Although the brushes looked as though they had been specifically designed for this job, they were actually produced to take samples from the opposite end of the body: cervical cells for screening tests.)

Meanwhile, I set out with a group of Lanoh girls to go fishing in the Air Bah River. We drove some distance from the village and then trekked into the rainforest. The first thing that struck me was how incredibly noisy it was: the trees seemed to be packed with highly vociferous but apparently invisible insects and birds. Down by the river, we took our shoes off and waded in, and the girls immediately started hunting for fish – with their hands and a shovel-shaped woven bamboo basket. They would turn smaller pebbles over and hold the basket downstream to catch any fish that would emerge, and fearlessly scrabble under larger rocks for fish that might be hiding there. I gradually grew braver – and managed to catch one fat tadpole. My Western sensitivities got the better of me, though, and while the girls proceeded to thread the fish they’d caught through the gills on to a forked twig – still alive – the tadpole lived to fight another day.

I sat down by a rock and watched the girls, almost completely submerged now, pushing their hands under a large boulder where, by their excited voices, they could obviously

just

feel fish with their fingertips. They laughed and splashed around in the river they’d known since childhood; they knew its twists and turns, and the boulders where fish would be hiding. And they were certainly adept at catching them: there would be fish for supper that night. But for these four young women in their late teens, it was also a group of friends having fun. It was a relic of an earlier way of living; what was work in the sense that they were serious about feeding themselves, was also something you did with friends, for yourself, friends and family. But, as more and more young Lanoh find paid work, it’s a way of life that may not exist for much longer. and

Later in the day I accompanied Alias and a younger man as they went on a hunting trip – armed with blowpipes. We sat at the top of a waterfall and I asked Alias about how life had changed for the Lanoh. Historically, the Lanoh would have lived in temporary, seasonal camps. The rainforest did not offer the sumptuous banquet that I first imagined it might. Hunting and gathering in this environment required specialist knowledge of which foodstuffs were edible and where to find them: it was hard work to subsist entirely on wild food, and the tribe would have ranged over a large territory. By the middle of the twentieth century, the Lanoh had begun to settle down and were semi-nomadic. Alias described how, when he was a child, the tribe would set up a camp and stay in it for one or two years, foraging in the surrounding area, before moving on. The territories were not exclusive: the broad area that the Lanoh occupied would be shared with other tribes, and they also recognised the Malay villages. At this time, the Lanoh had begun trading with the Malays, swapping jungle products such as rattan and resins for money, rice, sugar and other foodstuffs – and later, for motorbikes and televisions. They also began small-scale cultivation, of hill rice, tapioca and maize, often sowing the crops and moving away, then returning when the harvest was ready. In 1970, the Lanoh moved into Kampong Air Bah, and the nomadic way of life was replaced by a settled existence, with more cultivation of crops and less hunting and gathering. Rubber tree plantations created as part of the resettlement scheme also provided a source of income.

4

,

5

‘In the past we would search for food, rattan and wood,’ said Alias. ‘When I went hunting in the jungle with my father, we would hunt for food, like monkeys, squirrels and birds. There were lots of things you could get in there. Now, when we go to the jungle, we would look for money. Whatever we manage to get, we sell.’ The lives of the Lanoh had changed so much in just one generation. ‘In the past we were free and happy. We could go wherever we wanted to and do what we wanted. We could stay in the jungle and no one would bother us. But now it is difficult.’

But Alias still knew how to survive in the rainforest: he knew which plants were edible and which poisonous, and how to stealthily creep up and dispatch a monkey or a squirrel with a blowpipe. These skills were no longer vital to survival, in a time when cash could be earned and food could be grown or bought, but in spite of this, Alias still thought it important to pass on the knowledge and skills to the next generation: it was part of the Lanoh identity.

The blowpipe was a particularly important symbol of this hunter-gatherer character and most Lanoh men owned one. Alias showed me how his blowpipe had been made, from a very straight length of sewoor bamboo with no joints. The base of the blowpipe was decorated with an incised geometric design; each Semang group used a different motif, and the design was also important to the luck of the hunt. Alias was wearing his quiver, or

lek

, of darts, tied around his waist with string. The

lek

was made of a short length of bamboo, also decorated, with a woven rattan lid. The darts were produced from bertam palm, shaved down to a point at one end and dipped in ipoh toxin. Placing a dart in the bottom of the blowpipe, Alias then pushed a small wad of kapok ‘cotton’ in beneath it to stop it falling back out, and the weapon was primed and ready to use. We made our way down the river, Alias cautiously and silently moving around and occasionally lifting the blowpipe to his lips when he thought he was near to a quarry. But the jungle creatures were keeping themselves well hidden that afternoon. Alias had little chance of successfully creeping up on his potential dinner when he was being followed by a considerably less stealthy anthropologist.