The Indian Clerk (2 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

Such a statement is pure lunacy. And yet, here and there amid the incomprehensible equations, the wild theorems unsupported

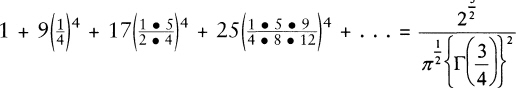

by proof, there are also these bits that made sense—enough of them to keep him going. Some of the infinite series, for instance,

he recognizes. Bauer published the first one, famous for its simplicity and beauty, in 1859.

But how likely is it that the uneducated clerk Ramanujan claims to be would ever have come across this series? Is it possible

that he discovered it on his own? And then there is one series that Hardy has never seen before in his life. It reads to him

like a kind of poetry:

What sort of imagination could come up with

that?

And the most miraculous thing—on his blackboard Hardy tests it, to the degree that he can test it—it appears to be correct.

Hardy lights his pipe and begins pacing. In a matter of moments his exasperation has given way to amazement, his amazement

to enthusiasm. What miracle has the post brought to him today? Something he's never dreamed of seeing. Genius in the raw?

A crude way of putting it. Still . . .

By his own admission, Hardy has been lucky. As he is perfectly happy to tell anyone, he comes from humble people. One of his

grandfathers was a laborer and foundryman, the other the turnkey at Northampton County Gaol. (He lived on Fetter Street.)

Later this grandfather, the maternal one, apprenticed as a baker. And Hardy—he really is perfectly happy to tell anyone this—would

probably be a baker himself today, had his parents not made the wise decision to become teachers. Around the time of his birth

Isaac Hardy was named bursar at Cranleigh School in Surrey, and it was to Cranleigh that Hardy was sent. From Cranleigh he

went on to Winchester, from Winchester to Trinity, slipped through doors that would normally have been shut to him because

men and women like his parents held the keys. After that, nothing impeded his ascent to exactly the position he dreamed of

occupying years ago, and which he deserves to occupy, because he is talented and has worked hard. And now here is a young

man, living somewhere in the depths of a city the squalor and racket of which Hardy can scarcely imagine, who appears to have

fostered his gift entirely on his own, in the absence of either schooling or encouragement. Genius Hardy has encountered before.

Littlewood possesses it, he believes, as does Bohr. In both their cases, though, discipline and knowledge were provided from

early on, giving genius a recognizable shape. Ramanujan's is wild and incoherent, like a climbing rose that should have been

trained to wind up a trellis but instead runs riot.

A memory assails him. Years before, when he was a child, his school held a pageant, an "Indian bazaar," in which he played

the role of a maiden draped in jewels and wrapped in some Cranleigh school version of a sari. A friend of his, Avery, was

a knife-wielding Gurkha who threatened him . . . Odd, he hasn't thought of that pageant in ages, yet now, as he remembers

it, he realizes that this paste and colored-paper facsimile of the exotic east, in which brave Englishmen battled natives

for the cause of empire, is the image his mind summons up every time India is mentioned to him. He can't deny it: He has a

terrible weakness for the gimcrack. A bad novel determined his career. In the ordinary course of things, Wykehamists (as Winchester

men were called) went to New College, Oxford, with which Winchester had close alliances. But then Hardy read

A Fellow of Trinity,

the author of which, "Alan St. Aubyn" (really Mrs. Frances Marshall), described the careers of two friends, Flowers and Brown,

both undergraduates at Trinity College, Cambridge. Together, they negotiate a host of tribulations, until, at the end of their

tenure, the virtuous Flowers wins a fellowship, while the wastrel Brown, having succumbed to drink and ruined his parents,

is banished from the academy and becomes a missionary. In the last chapter, Flowers thinks wistfully of Brown, out among the

savages, as he drinks port and eats walnuts after supper in the senior combination room.

It was that moment in particular—the port and the walnuts—that Hardy relished. Yet even as he told himself that he hoped to

become Flowers, the one he dreamed of—the one who lay close to him in his bed in dreams—was Brown.

And of course, here is the joke: now that he lives at Trinity, the real Trinity, a Trinity that resembles not in the least

"Alan St. Aubyn's" fantasy, he never goes after supper to the senior combination room. He never takes port and walnuts. He

loathes port and walnuts. All that is much more Littlewood's thing. Reality has a way of erasing the idea of a place that

the imagination musters in anticipation of seeing it—a truth that saddens Hardy, who knows that if ever he traveled to Madras,

steeped himself in whatever brew the real Madras really is, then that pageant stage at Cranleigh, bedecked with pinks and

blue banners and careful children's drawings of goddesses with waving multiple arms, would be erased. Avery, swaggering toward

him with his paper sword, would be erased. And so for this moment only can he take pleasure in imagining Ramanujan, dressed

rather as Avery was dressed, writing out his infinite series amidst Oriental splendors, even though he suspects that in fact

the young man wastes his days sorting and stamping documents, probably in a windowless room in a building the English gloom

of which not even the brilliant sun of the east can melt away.

There is nothing else to do. He must consult Littlewood. And not, this time, by postcard. No, he will go and see Littlewood.

Carrying the envelope, he will make the walk—all forty paces of it—to D staircase, Nevile's Court, and knock on Littlewood's

door.

E

VERY CORNER OF Trinity has a story to tell. D staircase of Nevile's Court is where Lord Byron once resided, and kept his pet

bear, Bruin, whom he walked on a lead in protest of the college rule against keeping dogs.

Now Littlewood lives here—perhaps (Hardy isn't sure) in the very rooms where Bruin once romped. First floor. It is nine o'clock

in the evening—after dinner, after soup and Dover sole and pheasant and cheese and port—and Hardy is sitting on a stiff settee

before a guttering fire, watching as Littlewood pushes his wheeled wooden chair from his desk and rolls himself across the

floor, without once averting his eyes from the Indian's manuscript. Will he crash into a wall? No: he comes to a halt at a

spot near the front door and crosses his legs at the ankles. Socks, no shoes. His glasses are tipped low on his nose, from

which little snorts of breath escape, stirring the hairs of a mustache that, in Hardy's view, does little for his face.

(Little for Littlewood.)

But he would never say so, even if asked, which he never would be. Although they have been collaborating for several years

now, this is only the third time that Hardy has ever visited Littlewood in his rooms.

" I have found a function which exactly represents the number of prime numbers less than x, ' " Littlewood reads aloud. "Too

bad he doesn't give it."

"I rather think he's hoping that by not giving it, he'll be able to entice me to write back to him. Dangling the carrot."

"And will you?"

"I'm inclined to, yes."

"I would." Littlewood puts down the letter. "Look, what's he asking for? Help in publishing his stuff. Well, if it turns out

there's something there, we can—and should—help him. Providing he gives us more details."

"And some proofs."

"What do you think of the infinite series, by the way?"

"Either they came to him in a dream or he's keeping some much more general theorem up his sleeve."

With his stockinged foot, Littlewood rolls himself back to his desk. Outside the window, elm branches rustle. It's the hour

when, even on a comparatively mild day like this, winter reasserts itself, sending little incursions of wind round the corners,

up through the cracks in the floorboards, under the doors. Hardy wishes that Littlewood would get up and stoke the fire. Instead

he keeps reading. He is twenty-seven years old, and though he is not tall, he gives an impression of bulk, of breadth—evidence

of the years he spent doing gymnastics. Hardy, by contrast, is fine-boned and thin, his athleticism more the wiry cricketer's

than the agile gymnast's. Though many people, men as well as women, have told him that he is handsome, he considers himself

hideous, which is why, in his rooms, there is not a single mirror. When he stays in hotels, he tells people, he covers the

mirrors with cloth.

Littlewood is in his way a Byronic figure, Hardy thinks, or at least as Byronic as it is possible for a mathematician to be.

For instance, every warm morning he strolls through New Court with only a towel wrapped around his waist to bathe in the Cam.

This habit caused something of a scandal back in 1905, when he was nineteen, and newly arrived at Trinity. Soon word of his

dishabille had spread as far as King's, with the result that Oscar Browning and Goldie Dickinson started coming round in the

mornings—though neither had a reputation for being an early riser. "Don't you love the springtime?" O. B. would ask Goldie,

as Littlewood gave them a wave.

Both O. B. and Goldie, of course, are Apostles. So are Russell and Lytton Strachey. And John Maynard Keynes. And Hardy himself.

Today the Society's secrecy is something of a joke, thanks mostly to the recent publication of a rather inaccurate history

of its early years.

Now anyone who cares to know knows that at their Saturday evening meetings, the "brethren"—each of whom has a number—eat "whales"

(sardines on toast), and that one of them delivers a philosophical paper while standing on a ceremonial "hearthrug," and that

these papers are stored in an old cedarwood trunk called the "Ark." It is also common knowledge that most of the members of

"that" society are "that" way. The question is, does Littlewood know? And if so, does he care? Now he stands from his chair

and walks, in that determined way of his, to the fire. Flames rise from the coals as he stokes them. The cold has got to Hardy,

who in any case feels ill at ease in this room, with its mirrors and the Broadwood piano and that smell that permeates the

air, of cigars and blotting paper and, above all, of Littlewood—a smell of clean linens and wood smoke and something else,

something human, biological, that Hardy hesitates to identify. This is one of the reasons that they communicate by postcard.

You can speak of Riemann's zeta function in terms of the "mountains" and "valleys" where its values, when charted on a graph,

rise and fall, yet if you start actually imagining the climb, tasting the air, searching for water, you will be lost. Smells—of

Littlewood, of the Indian's letter—interfere with the ability to navigate the mathematical landscape, which is why, quite

suddenly, Hardy finds himself feeling ill, anxious to return to the safety of his own rooms. Indeed, he has already got up

and is about to say goodbye when Littlewood rests his hot hand on his shoulder. "Don't go just yet," he says, sitting Hardy

down again. "I want to play you something." And he puts a record on the gramophone.

Hardy does as he is told. Noise issues forth from the gramophone. That's all it is to him. He can ascertain rhythm and patterns,

a succession of triplets and some sort of narrative, but it gives him no pleasure. He hears no beauty. Perhaps this is due

to some deficiency in his brain. It frustrates him, his inability to appreciate an art in which his friend takes such satisfaction.

Likewise dogs. Let others natter on about their sterling virtues, their intelligence and loyalty. To him they are smelly and

annoying. Littlewood, on the other hand, loves dogs, as did Byron. He loves music. Indeed, as the stylus makes its screechy

progress across the record, he seems to enter into a sort of concentrated rapture, closing his eyes, raising his hands, playing

the air with his fingers.

At last the record finishes. "Do you know what that was?" Littlewood asks, lifting the needle.

Hardy shakes his head.

"Beethoven. First movement of the 'Moonlight Sonata.'"

"Lovely."

"I'm teaching myself to play, you know. Of course I'm no Mark Hambourg, and never will be." He sits down again, next to Hardy

this time. "You know who it was who first introduced me to Beethoven, don't you? Old O. B. When I was an undergraduate, he

was always inviting me to his rooms. Maybe it was the glamour of my being senior wrangler. He had a pianola, and he played

me the 'Waldstein' on it."

"Yes, I knew he was musical."

"Peculiar character, O. B. Did you hear about the time a party of ladies interrupted him after his bathe? All he had was a

handkerchief, but instead of covering his privates, he covered his face.

'Anyone

in Cambridge would recognize my

face,

he said."

Hardy laughs. Even though he's heard the story a hundred times, he doesn't want to take away from Littlewood the pleasure

of thinking that he is telling it to him for the first time. Cambridge is full of stories about O. B. that begin just this

way. "Did you hear about the time O. B. dined with the king of Greece?" "Did you hear about the time O. B. went to Bayreuth?"

"Did you hear about the time O. B. was on a corridor train with thirty Winchester boys?" (The last of these Hardy doubts that

Littlewood has heard.)

"Anyway, ever since then, it's been Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart for me. Once I learn, they're the only composers I'll play."

He gets up again, removes the record from the gramophone and returns it to its sleeve.

Dear God, please let him take out another record and put it on the

gramophone. I'm in the mood for music, hours and hours of music.

The ruse works. Littlewood looks at his watch. Maybe he wants to work, or write to Mrs. Chase.

Hardy is just reaching for Ramanujan's letter when Littlewood says, "Do you mind if I keep that tonight? I'd like to look

it over more carefully."

"Of course."

"Then perhaps we can talk in the morning. Or I'll send you a note. I rather imagine I'll be up most of the night with it."

"As you please."

"Hardy—in all seriousness, maybe we should think about bringing him over. Make some enquiries, at least. I know I may sound

as if I'm jumping the gun . . ."

"No, I was thinking the same thing. I could write to the India Office, see if they've got any money for this sort of thing."

"He may be the man to prove the Riemann hypothesis."

Hardy raises his eyebrows. "Really?"

"Who knows? Because if he's done all this on his own, it might mean he's free to move in directions we haven't thought of.

Well, goodnight, Hardy."

"Goodnight."

They shake hands. Shutting the door behind him, Hardy hurries down the steps of D staircase, crosses Nevile's Court to New

Court, ascends to his rooms. Forty-three paces. His gyp has kept his fire going; in front of it Hermione now lies curled atop

her favorite ottoman, the buttoned blue velvet one.

"Capitonne"

Gaye, who knew about such things, called the buttoning. He even had a special cover made for the ottoman, so that Hermione

could scratch at it without damaging the velvet. Gaye adored Hermione; spoke, in the days before he died, of commissioning

her portrait—a feline Odalisque, nude but for an immense emerald hung round her neck on a satin ribbon. Now the cover itself

is in tatters.

Should

they bring the Indian to England? As he mulls over the idea, Hardy's heart starts to beat faster. He cannot deny that it excites

him, the prospect of rescuing a young genius from poverty and obscurity and watching him flourish . . . Or perhaps what excites

him is the vision he has conjured up, in spite of himself, of Ramanujan: a young Gurkha, brandishing a sword. A young cricketer.

Outside his window, the moon rises. Soon, he knows, the gyp will arrive with his evening whiskey. He will drink it by himself

tonight, with a book. Curious, the room feels emptier than usual—so whose presence is he missing? Gaye's? Littlewood's? An

odd sensation, this loneliness that, so far as he can tell, has no object, at the other end of which no mirage of a face shimmers,

no voice summons. And then he realizes what it is that he misses. It is the letter.