The Indian Clerk (50 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

We left soon after. On the way back to London we did not speak much. Each of us had private troubles to contemplate. Much

else was wrong in our lives besides the poor Indian trapped in a dismal hydro in Derbyshire. Others rode in that car too,

a woman who lived in Treen and a soldier who might very well have been dead.

That spring, the Russell affair erupted again. In February, Russell published his notorious article in the

Tribunal,

in which he wrote that whether or not the American garrison, then en route to Europe, proved "efficient against the Germans,"

they would "no doubt be capable of intimidating strikers, an occupation to which the American Army is accustomed at home."

This reckless sentence resulted in a visit to his flat by two detectives, his subsequent arrest on the charge of making "certain

statements likely to prejudice His Majesty's relations with the United States of America," his conviction on that charge,

and a sentence of six months in Brixton prison, at the gates of which he arrived early in May in a taxi. Prison life seemed

to suit him. The sameness of the days, he said, made him wonder if his true vocation was to be a monk in a contemplative order,

and he got a lot of philosophical writing done. In the meantime, at Trinity, Thomson was inducted as the new master, and while

we hoped his arrival (and Butler's departure) would help our case, we didn't bank on it.

So far as the war went, the tide appeared to be turning against Germany. For any Englishman who was alive then—even a pacifist

like me—it is still a humiliating thing to admit that this was entirely due to the arrival of you Americans. Yet the fact

is, your troops made a huge difference, and the day that news drifted back to Cambridge of your victory at Cantigny is one

I shall never forget. It was the end of May—what should have been the season of balls—and while I recall working hard to hold

back in myself any emotion as reckless as optimism, I also recall thinking, "Yes, the war will end. There will once again

be life without war." Make no mistake, our troubles continued. Young men kept dying, while at Cambridge a perfectly benign

librarian named Dingwall was fired for his antiwar views. And yet the charge in the air was as distinct as the smell of the

summer stealing back into England and brushing away the last dirty snow piles that have survived the spring. This, I recognized,

was what it felt like to be on the winning side, and though I didn't give up my pacifist stance, secretly I reveled in the

sensation.

In June I returned to Cranleigh, to Gertrude, whose passive stubbornness had proven effective: I had given up any hope of

persuading her to sell the house. We were friends again, and resumed our usual summer habits, even the games of Vint with

Mrs. Chern, whose niece Emily made a redoubtable fourth. Miss Chern, whose mother was American, was reading mathematics at

Newnham—she kept a newspaper photograph of Philippa Fawcett, the woman who had beaten the senior wrangler, over her desk—and

asked often after Ramanujan, whom she looked upon as a kind of mysterious prophet. Indeed, many people looked upon him this

way. Clippings of articles about him periodically came my way, courtesy of friends in America and Germany and India, articles

misrepresenting his achievements and offering somewhat romanticized versions of his story. From reading them, you might have

thought he spent his days parading about Cambridge performing feats of mental arithmetic while a retinue of admirers strewed

flowers in his wake, when in fact he remained under lock and key at Matlock.

I wondered if he had any idea that he was becoming a famous man, or if sending him some of the articles would contribute to

his improvement. For he was improving, if only a little. As Littlewood and I had hoped, the news that he had been elected

an F.R.S. boosted his spirits to some degree. Unfortunately, my efforts to persuade Dr. Ram to lift the ban on travel and

allow him to go to London for the induction ceremony proved unsuccessful, and he had to write to the Society to ask if the

ceremony might be postponed. I don't know that it mattered to him much. The worst of the winter weather had passed, resolving,

at least temporarily, the crisis of cold, and though the crisis of food persisted, at least he was working. Indeed, he had

entered into a new period of productivity, sending out from the bathrooms of Matlock all sorts of new contributions to partitions

theory, including the famous set of identities that you know today as the Rogers-Ramanujan identities.

And that was the least of it. During May and June of 1918 it seemed that every week I would receive at least two or three

letters from him, most concerning a paper we were writing together on the expansions of elliptic modular functions, some concerning

partitions, still others offering, almost as afterthoughts, those odd, seemingly random arithmetical observations of which

he made a specialty. It may seem strange to a non-mathematician that when I remember Ramanujan, I remember, in addition to

his barking laugh and his black eyes and his scent, the fact that in a letter from Matlock he once threw off, almost as an

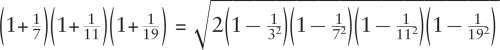

aside, the following remarkable equation:

And yet it was just such identities upon which his imagination, in its wanderings, would stumble; that he would pick up like

curious pieces of fauna to study and preserve and then later, with an ingenuity that always took me by surprise, pull out

of his sleeve and reveal to be the missing pieces in complex proofs to which, on the surface at least, they bore no connection.

Since he had become ill, I had missed his habit of arriving in my rooms in the mornings bearing the fruits of his nightly

labors, the messages that he claimed the goddess had written on his tongue. Now those messages came in the form of letters,

and though I lamented his remoteness, nonetheless I was glad to see that he was back on form.

In July, I went to see him, once again, at Matlock. As a treat, I brought along Gertrude and young Emily Chern, who undertook

the expedition with the noble gravity of a disciple. Summer weather had remade Matlock, which no longer looked like a resort

out of season. The trees were in flower, and the verandah on which we had discovered Ramanujan freezing the January before

now provided an amenable and comparatively warm oasis.

He was not alone. With him was a young Indian who stood to greet us almost as soon as we walked through the door. "Mr. Hardy,

what an honor," the Indian said, taking my hand. "I am Ram—A. S. Ram, not to be mistaken for Mr. Ramanujan's doctor, who is

L. Ram. You may call me S. Ram if you think that will help to avoid confusion."

"How do you do," I said. And I introduced him to Gertrude and Miss Chern, whose hand he kissed.

We sat down. He was a good-looking youth, not tall, with hair at once curlier and finer than most of his countrymen's. As

he rapidly explained, he had met Ramanujan back in 1914, when Ramanujan had just arrived in England and both of them were

staying at the Indian Students' Hostel on Cromwell Road in London. "We struck up a friendship," he told us, "though very quickly

circumstances and the war divided us. Mr. Ramanujan went to Cambridge, and I took a position as an assistant engineer on the

North Staffordshire Railway. I have neglected to mention that I come from Cuddalore, near Madras, and have a degree in Civil

Engineering from King's College, not the famous King's College of Cambridge but the one at University of London. In any case,

when the war broke out, I joined His Majesty's forces, and after sixteen months with the army, a small part of which I spent

with the Indian contingent, I was released to work on munitions at Messieurs Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company in Jarrow.

I continue to be employed there—but you are probably wondering how I came to be back in contact with Mr. Ramanujan and what

I am doing here today!" And here he laughed—his laugh high, shrill, distinctly out of tune with his speaking voice, which,

though swift, was deep.

He paused, took a breath. Gertrude was staring at him in amazement. I suppose in those gloomy days we were not used to talkers

of this vintage.

He went on. As he spoke I glanced at Ramanujan, who was in turn gazing at his own lap. I had hoped he would look healthier

than he did; in fact he looked much the same as he had in January—if anything a bit gaunter. In some ways, though, gauntness

suited him; brought out his beauty. He was wearing a yellow jumper that contrasted garishly with his skin, and Miss Chern

was gazing at him with the sort of adoration that young girls usually reserve for cinema stars. It was obvious that she was

not listening to a word that S. Ram was saying.

As for this S. Ram, it was becoming rapidly clear to Gertrude and me what he was: an admirer, a "fan," if you will, who had

taken it upon himself to oversee Ramanujan's rehabilitation. And like most "fans," he was really much more interested in exhibiting

his own virtue and selflessness than in contributing to the well-being of the friend on whose behalf, he was telling us, he

had just taken a "most beastly journey, all night long, the train stopping all the time." For S. Ram, it seemed, had arrived

at Matlock two days previously and been put up in an empty room there. "You see," he said, "since the rationing scheme took

effect here in England, my good people back in Cuddalore have worried, it seems to me, rather excessively about my condition,

and thinking I must be starving they have made it their habit to send me by post parcel after parcel of eatables, so much

that it remains a problem how I am to dispose of these and I have had to send a cable home saying 'Stop pause Sending pause

Food pause Ram.' I should put in here that while I am a vegetarian, I am not of the same caste as Mr. Ramanujan, thus I have

not been, since my arrival here in England, a vegetarian staunch and strict. For instance, I take eggs on occasion, as well

as beef tea and sometimes Bovril. You see, I am determined to keep up my health, as lately I have had a bit of luck and, on

condition that I pass a test in horse riding in Woolwich at the end of this month, I have been promised release by the army

so that I may sail for home on or about the end of September next in order to take up a civilian service position in the Indian

Public Works department. So I have of late been eating eggs to keep up my strength in order that I can stick to my work at

Palmers and also have some riding practice at Newcastle-Upon-Tyne." Again he paused. Through this whole monologue, it seemed,

he had not taken a breath. Would he go on like this all afternoon? I looked to Gertrude for help, which, to my relief, she

provided. (As she later explained to me, in her work at St. Catherine's she had become accustomed to dealing with men and

women of this stripe, inveterate talkers whose fondness for their own voices was in fact symptomatic of a mental disorder

called logorrhea. "Many teachers are logorrheacs," she said.)

Now she turned her steady, prim gaze on S. Ram and said, "Quite fascinating. And tell me, how did you come to renew your acquaintance

with Mr. Ramanujan?"

Across the table, S. Ram looked at her with a kind of gratitude; it seemed that he appreciated being brought back to the subject

at hand. "You see," he said, "it was the food," and proceeded to explain to us how, upon finding himself with a surplus of

"eatables" sent over by his parents, he remembered Ramanujan and his fondness for Madrasi-style dishes. "It was at this point,"

he said, "that I wrote to you—though you may not recollect it, Mr. Hardy."

"You wrote to me?"

"Yes," S. Ram said. "I wrote inquiring after Mr. Ramanujan's health and to see if he would share some of these foodstuffs

with me. And you replied giving me his address as Matlock House, Matlock, Derbyshire."

"Did I? Oh, of course I did."

"And so I began a correspondence with Ramanujan, and in response to his request for some ghee—this is Indian clarified butter,

Miss Hardy—I forwarded to him intact two parcels containing three bottles, two of ghee and one of gingelly oil for frying

purposes, as well as a small quantity of Madras pickle. As you are no doubt aware of the difficulty and bother involved in

sending bottles by post, you can well imagine that it was most convenient merely to send on the packages prepared by my people,

already sealed."

"Much more convenient," I said.

"And of course they had sent much more than I could possibly consume. I then proposed a visit. Owing to changes in my schedule

I was unable to postpone my holidays to July thirty-first to suit my riding examination, and had no choice but to take the

previous fortnight. With nothing particular to do during this holiday I wrote to Ramanujan . . . and now I am here." He smiled.

Ramanujan continued to gaze into his lap.

"And I'm sure," Gertrude said, "that Mr. Ramanujan has been grateful for your company. Haven't you, Mr. Ramanujan?"

"Oh yes," Ramanujan said.

"Yes, we have been talking all the time," S. Ram said. "We have discussed all sorts of topics, personal, political, war, Indian

social customs, Christian missions, marriage, the university, the Hindu question, and I can say without question that at no

time did Mr. Ramanujan seem to me at all to have 'gone off the rails.'"