The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (104 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

HIS THOUGHTS:

“I regret to say that we of the FBI are powerless to act in cases of oral-genital intimacy, unless it has in some way obstructed interstate commerce.”

—D.W.

The Modern Bluebeard

HENRI DÉSIRÉ LANDRU (Apr. 12, 1869–Feb. 25, 1922)

HIS FAME:

In France, between 1914

and 1919, 10 women and a boy mysteriously vanished. Though their bodies

were never found, Henri Landru was

arrested, tried, and convicted of their

murder. In addition to being adjudged

guilty of mass murder, Landru was

accused of having had relations with—

and then swindling—at least 283 women

of modest means, mostly middle-aged.

HIS PERSON:

Paris-born Henri Landru

was short, frail, bespectacled, red-bearded,

and bald and had large, luminous, hyp-

Landru and Fernande Segret, who survived

notic, black eyes—an unlikely-looking

sort to have seduced as many women in five years as Don Juan did in a lifetime.

Landru’s father was a stoker in a foundry, his mother a part-time seamstress. He attended Catholic school and sang in the church choir. In his early years he worked as an architect’s draftsman, and later served in the French army. In 1900, while working unsuccessfully as a dealer in secondhand items, he forsook the straight and narrow and embarked upon a life of petty thievery and fraud. His first recorded crime was an attempt at defrauding a widow with a promise of marriage, and between 1900 and 1914 he did several prison terms for fraud. In 1914 he was sentenced

in absentia

to four years on Devil’s Island, and he thereafter eluded police by using various aliases. In 1919 he was captured by the police, who were looking into the disappearance of two women. An incriminating diary was produced, and 295

bone fragments believed to belong to two or three different corpses were found in his kitchen stove. He was charged with 11 murders, and following a widely publicized trial during which he calmly and coolly stonewalled all attempts to break him down (“the women went where their destiny called them”), he was sentenced to the guillotine. “Ah, well,” he said as he was led to his death. “It is not the first time an innocent man has been condemned…. I will be brave. I will be brave.”

SEX LIFE:

Landru’s first recorded affair was with his young cousin, Marie Remy. He was 22, she 16. She became pregnant and subsequently they married and had four children. He remained a loving husband and father, although he did not live with his family in later years.

Landru met his victims in various ways. He placed lonely-hearts ads in Paris newspapers. He answered similar ads placed by single women. He dabbled in

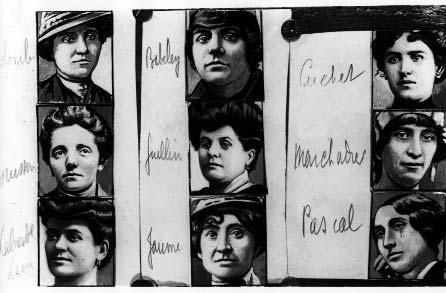

Landru’s victims

“matrimonial agencies.” He made casual pickups on the street. His victims, mostly plainlooking, ranged from a former prostitute to a 19-year-old servant girl (probably just an idle affair, for she had little money). When apprehended he was living with his young, attractive mistress, Fernande Segret, a self-described “lyric artist.” Her recollection of how they met is representative of his technique. Segret and a girl friend had just descended from a tram. “Scarcely had we gone a few yards … when a man accosted us, saluted us very respectful-ly, and addressing himself to me, asked if we would allow him to accompany us for a few minutes…. We refused … and quickened our pace to get away from him. But our follower would not be shaken…. He suggested that young girls in Paris go out all too often alone with the risk of being accosted by bad characters, and all sorts of annoyances from men. Such a statement made us laugh loudly; our follower took advantage of it to stay.” A few days later, at dinner with her family, she said, “He talked on abundantly with a most lively wit, and every subject he touched he seemed to be at home in. His courteous and agreeable manners impressed me. Without ever forgetting that he was in the presence of ladies he poured out jokes, witty retorts, and even juggled for us with the napkin rings … all the time garnishing his talk with the most wonderful puns.”

According to his records Landru enjoyed about 50 women a year, and sometimes met with as many as seven a day. At his trial, Segret, the only woman to live with Landru during that period and remain alive—in fact, she had four children by him—testified that she found him an extremely passionate but normal lover. “I have not a single reproach against him. I loved him very deeply. I was very, very happy with him.” Many of the women he seduced and abandoned were questioned, but not one testified against him. Some even called him kindly, considerate, and affectionate. His wife maintained, “My misfortune has been to love my husband too well.”

QUIRKS:

Landru was a meticulous, parsimonious, abstemious, vain man who compulsively kept a diary of all his expenses, conquests, and daily movements.

Next to his victims’ names he made copious notes like “Madame Jaume: 39, looks younger…. Very strong Catholic. Afraid of divorce.” And then there were the ominous notations: “1 single and 1 return ticket.” Other entries included the purchase of 7 saw blades, 7 dozen hacksaws, ax blades, and circular saws. For what possible use? In searching his villa police found a variety of women’s clothing, women’s false hair, dental plates, and trinkets as well as some male costumes of the 18th century. Landru’s courtroom behavior was eccentric, belying the seriousness of the charges. He was a master of deadpan humor. One day he informed the judge that he wished to make a statement. Landru bowed to the court and said that he had to confess to having committed adultery with hundreds of women and that in so doing he’d grievously wronged his wife.

When asked, before the guillotining, why he’d trimmed his beard, he replied simply that he wanted to please the ladies.

The final irony was that Landru worked so hard for so little. His crimes netted him in all about $8,000.

AFTERMATH:

In 1968, almost a half century after Landru had gone to his Maker, a French newspaper announced that this modern Bluebeard’s confession had been found. Scribbled in Landru’s hand on the back of a framed sketch he had presented to one of his lawyers before going to the guillotine was the following: “I did it. I burned their bodies in my kitchen oven.” And what had happened to Landru’s mistress, Fernande Segret? She was thought long dead when a French film,

Landru

, written by Françoise Sagan, was exhibited in movie theaters worldwide. Suddenly Segret reappeared, a governess working in Lebanon, quite alive. She sued the French filmmakers for 200,000 francs and settled for 10,000. With this tidy sum she retired comfortably to a senior citizens’ home in Normandy. But she was notorious again, and recognized. To rid herself of Landru forever she finally committed suicide by drowning.

—C.H.S.

A Woman Ahead Of Her Time

MARIA MONTESSORI (Aug. 31, 1870–May 6, 1952)

HER FAME:

Maria Montessori pioneered preschool education, first by teaching the mentally retarded, later by devising methods still used in Montessori schools worldwide today. Her pedagogical revolution occurred so

rapidly that she was known as an “educational wonder-worker” in the U.S.

before WWI. The first Montessori—

trained students included Douglas

Fairbanks, Jr., and the grandchildren of

Alexander Graham Bell.

HER PERSON:

Maria Montessori

believed in action, not rhetoric, and

pointed to her achievements as evidence

of what women could accomplish

through work. She started early, winning her astonished father’s permission

to study engineering at the age of 13.

She conquered the opposition of the

medical authorities in Rome (by

appealing to Pope Leo XIII for support), entered medical school, and finished with double honors and a standing ovation from her colleagues. A reporter sent to interview Italy’s first female doctor arrived expecting a stern, bony woman in men’s clothing. He was delighted to find Maria attractive and gracious, and noted the flowers, needlework, and musical scores scattered among the chemistry experiments and medical books in her apartment. “The delicacy of a talented young woman combined with the strength of a man—an ideal one doesn’t meet with every day,” was the reporter’s enthusiastic pronouncement.

Maria soon became resentful of this sort of publicity and vowed, “My face will not appear in the newspapers anymore and no one will dare to sing of my so-called charms again. I shall do serious work!”

She brought a clinician’s eye to her specialty, children’s nervous disorders, and realized that retarded children were bright enough to invent games to overcome their boredom. Maria became one of the first to teach the retarded, and went on to open Casa dei Bambini (“Children’s House”) for neglected Roman slum children in 1907. The success of her methods was so spectacular (some of her retarded students were getting normal-level test scores) that she finally gave up medicine to devote her full time to training teachers and writing and lecturing about her program. Called by the

Times

of London “the best type of woman a country could hope to produce,” Montessori continued working until her death at 81 of a cerebral hemorrhage.

SEX LIFE:

In 1896, when she was 26, Maria was working in the psychiatric clinic of the University of Rome as a researcher. There she met Giuseppe Montesano, an assistant doctor. A year later Maria joined the clinic staff as an assistant doctor and subsequently worked alongside Dr. Montesano. In this period, Maria’s friendship with Montesano ripened, and the two became lovers. Soon Maria was pregnant. On Mar. 31, 1898, she gave birth to a child out of wedlock, a son she and Montesano named Mario.

Convinced by her mother that a scandal could destroy her career, Maria turned her son over to a wet nurse. Eventually a family in the country took the boy and raised him, keeping details of his birth a secret. Meanwhile Maria and Montesano had agreed not to marry each other and had pledged not to marry anyone else. But Maria’s lover broke his word and did marry another.

By then Maria and Montesano were codirectors of the State Orthophrenic School of Rome (an institution for the mentally retarded). Dismayed by her partner’s action, Maria resigned as head of the school and broke off all ties with Montesano. Her one experience with love had been tragic, and Maria Montessori never again opened her heart to a man.

Meanwhile Maria’s seven-year-old son, Mario, was attending a boarding school near Florence. From time to time the boy was visited by a “beautiful lady.” Mario began to believe that this lady was his mother. Yet Maria did not publicly acknowledge Mario until 54 years after his birth, when her will revealed him as “

il mio figlio

” (“my son”). A year after Maria’s mother died, Mario, now 15, confronted Maria and said, “I know you are my mother.”

When he asked to leave his boarding school to live with her, she did not object, but she insisted that he start using her surname. So Maria kept her agreement to protect her former lover and, in a way, denied his existence at the same time. Mario followed his mother into the field of preschool education and became her constant companion, even after he married and had four children of his own. For the rest of his mother’s life Mario was identified as her adopted son, nephew, or secretary.