The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (32 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

SEX LIFE:

In keeping with his masculine image, Hemingway portrayed himself as a great lover. He told Thornton Wilder that as a young man in Paris, his sex drive was so strong he had to make love three times a day; also he ostentatious-ly consumed sex-sedating drugs to quiet his raging libido. His family, however, reported that he didn’t even begin dating until he was a junior in high school.

(“About time,” they said.) He was never comfortable with casual sex, although he later boasted he was “an amateur pimp.” He compared intercourse to bicycle racing, in that the more you do it, the better you get at it.

Hemingway liked to dominate his women, believing that the man “must govern” sexual relationships. Three of his four wives appear to have accepted that rule. The exception was his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, who said afterward that “Papa” Hemingway had no redeeming qualities outside of his writing.

(Hemingway called their marriage his “biggest mistake.”) In his letters, Hemingway told of having many unusual bed partners, including a black harem he maintained while on an African safari. His strident

The Pen Is Prominent

/ womanizing led contemporaries to question his manhood. Some observers, including former mentor Gertrude Stein, implied that he was a latent homosexual. In fact, on one occasion in Spain, while walking to the bull ring with his friend Sidney Franklin, the Brooklyn-born matador, Hemingway spotted a very obvious homosexual across the street “just minding his business.” Hemingway snorted, “Watch this.” He strode across the street and without warning smashed his fist into the man, knocking him down and hurting him. Satisfied, Hemingway rejoined Franklin. However, there is certainly no evidence to suggest that Hemingway ever had a homosexual relationship; he himself commented that he had been approached by a man only once in his life.

“‘Course, Hemingway’s big problem all his life, I’ve always thought,” Sidney Franklin once told author Barnaby Conrad, “was he was always worried about his

picha

[penis]. The size of it, that is.” “Small?” Conrad wondered. Sidney Franklin “solemnly held up the little finger of his left hand with his thumbnail at the base,” Conrad reported. “He appraised it with a critical eye; then he raised his thumbnail up a fraction of an inch in reevaluation. ‘’Bout the size of a thirty-thirty shell,’ he said.”

Papa Hemingway was a straight man in bed, and he preferred women who

“would rather take chances than use prophylactics.” He abhorred any sexual arrangement that violated his sense of propriety. He wasn’t always the best performer and sometimes experienced stress-induced impotence.

SEX PARTNERS:

Hemingway boasted of his sexual prowess, claiming he had made love to a wide variety of women, including Mata Hari, Italian countesses, a Greek princess, and obese prostitutes in Michigan, where he spent many youthful summers. He also claimed he had made love to some of Havana’s most outrageous prostitutes, who bore such nicknames as Xenophobia, Leopoldina, and the International Whore. In truth, his relationships were considerably more chaste than he portrayed them, and his attitudes toward sex were almost prudish.

His “loveliest dreams” were inhabited by Greta Garbo and his friend Marlene Dietrich. In real life he preferred submissive, shapely blondes or redheads. Friends and acquaintances thought him “a Puritan,” and Hemingway himself blushed when accosted by a prostitute, feeling that only those “in love” could make love.

Married four times (and producing a total of three sons), he always regarded his divorce from first wife, Hadley Richardson, as a “sin” he could never expiate.

Although their first few years together were nearly ideal, their marriage was doomed when Hemingway met and fell in love with Pauline “Pfife” Pfeiffer, a beautiful sycophant who was to become his second wife. Hadley agreed to a divorce only after she had forced Pauline and Ernest to stay apart for 100 days.

Hemingway’s second marriage lasted 12 years on paper but far less in reality. The relationship ended for sexual reasons; after Pauline twice gave birth by Caesarean section, they had been forced to practice coitus interruptus because her Catholicism precluded the use of prophylactics.

Hemingway met his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, while reporting on the Spanish Civil War from Madrid. They were quickly drawn to each other, but

their passions cooled after marriage, and they were divorced five years later, in 1945. It was Ernest’s shortest marriage and a cosmic mismatch. Ernest did not like Martha’s independence (she was an accomplished writer in her own right) or her sharp tongue. He wanted blind adoration and submission, which Martha could not give any man.

Hemingway’s fourth wife, Mary Welsh, was in many ways made to order.

She was patient, worshipful, and beautiful (and nine years younger than Hemingway). He called her his “pocket Rubens.” The marriage lasted for the remainder of Hemingway’s life largely because Mary overlooked his often difficult behavior. Hemingway continued to enjoy a number of dalliances and made no effort to keep them secret.

As a young man he had preferred older women (Hadley was eight years his senior). From middle age on, he enjoyed the company of much younger women. A number of these women seemed to be models for Hemingway’s fictional characters—one may have inspired Brett Ashley in

The Sun Also Rises

and the other may have inspired Renata in

Across the River and into the Trees

, but none won his heart completely. He never let them get too close lest they try to run his life. “I know wimmins,” he told one friend, “and wimmins is difficult.”

QUIRKS:

Hemingway had several unusual theories about sex. He believed that each man was allotted a certain number of orgasms in his life, and that these had to be carefully spaced out. Another theory was that if you had sex often enough, you could eat all the strawberries you wanted without contracting hives, even though you were allergic to the fruit.

HIS ADVICE:

From

Death in the Afternoon

: “If two people love each other, there can be no happy end to it, for one of them must die and the other remain bereft.”

—J.A.M.

The Indefatigable Egotist

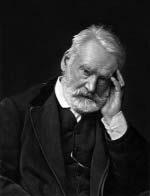

VICTOR HUGO (Feb. 26, 1802–May 22, 1885)

HIS FAME:

Hugo was known to his contemporaries as a champion of the Romantic movement, to literary critics primarily for his poetry, and to general readers then and now for his epic novels

Les Misérables

and

The Hunchback

of Notre Dame

.

HIS PERSON:

“Victor Hugo was a madman who believed himself to be Victor Hugo,” said the poet Jean Cocteau in summing up the extravagances and contradictions of a man who was larger than life both in literature and in love.

This supremely self-centered genius championed the rights of the poor and

The Pen Is Prominent

/ the downtrodden at the same time that

the downtrodden at the same time that

he emblazoned his walls with the motto

Ego Hugo

(“I, Hugo”). He amassed a

fortune, yet insisted on being buried in

a pauper’s coffin.

He was one of the literary center—

pieces in a nation and a century rich in

writers, and a political force in a time of

turmoil and change. An immense man

of gargantuan energy and robust health,

he slept less than four hours a night,

wrote standing up, and boasted that he

never had a thought or a sensation that

was not grist for his writer’s mill.

His disillusionment with the Second Empire of Louis Napoleon drove

him into exile in 1851, and for nearly

20 years he lived and worked on the Channel Island of Guernsey, creating a bizarre and ornate personal environment of architectural whimsy, made up of secret staircases, hidden rooms, and eccentric decorations. Here he wrote feverishly and explored the occult.

When he finally returned to France, he was again active in politics and literature, vigorous almost to the end. His dying words echo the contradictions of his life: “I see a black light.”

SEX LIFE:

When Hugo married at the age of 20, he was a virgin, but on his wedding night he coupled with his unsuspecting young wife, Adèle Foucher, nine times. She became exhausted by his sexual athleticism, and after five difficult pregnancies in eight years, she called a halt to their sex life. The marriage was shaken further when Adèle fell in love with Hugo’s friend, the famous literary critic Sainte-Beuve. Although the affair probably was not consummated, it nearly led to a duel between the two men.

The rupture with Adèle only temporarily disrupted Hugo’s sex life. In fact, his appetite had merely been whetted by his wife. He had been married 11 years and was world-famous for

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

when in 1833 he began an affair with the raven-haired, dark-eyed beauty Juliette Drouet. An actress and the mistress of a series of famous and wealthy men, she taught him the varieties of sensual pleasure. He was soon able to boast, “Women find me irresistible.”

And obviously they did. He began one of the most amazingly active sex lives ever recorded. It was not unusual for him to make love to a young prostitute in the morning, an appreciative actress before lunch, a compliant courtesan as an aperitif, and then join the also indefatigable Juliette for a night of sex. He maintained a certain level of activity almost to his deathbed; diary entries at the age of 83 record eight bouts of love over the four months before his death.

SEX PARTNERS:

He craved affairs with women who were passionate, witty, and challenging, but he often settled for sheer numbers. His powerful personality and his fame were strong aphrodisiacs, and he enjoyed a dazzling parade of willing partners. They were almost exclusively young; in fact, as he grew older, often young enough to be his granddaughters. He was perfectly open to having liaisons with married women, but not if they were living with their husbands. Any other woman, or girl, who was young, amenable, and attractive was fair game.

Juliette, who was the great love of his life, tolerated his prodigious activity. But by the time she was in her 30s her beauty had begun to fade—no doubt in part because of the cloistered existence Hugo forced upon her. By 1844 she had been temporarily displaced by Léonie d’Aunet, a young noblewoman who had run away with a painter. The affair turned into a shocking scandal when Léonie’s jealous husband arranged to have the couple tailed by the police, who caught them

in flagrante delicto

. Although Hugo escaped punishment by claiming his privileges as a member of the peerage, Léonie was thrown into jail for adultery. Upon her release from prison, Hugo divided his time equally for a while between Juliette and her. Eventually Juliette’s absolute devotion won out, however, and Léonie was deposed.

Juliette’s reinstatement as his primary love did not in any way limit the scope of Hugo’s conquests. She herself estimated that he had sex with at least 200 women between 1848 and 1850. Even at age 70 he managed to seduce the 22-year-old daughter of writer Théophile Gautier, and it is possible that he was carrying on an affair with Sarah Bernhardt simultaneously.

Despite the myriad women who claimed his attentions, Hugo always returned to Juliette as his “true wife.” Their love affair lasted 50 years. During most of that time they had to live separately. When possible, Hugo visited her every day. As for Juliette, her devotion was unswerving. She wrote him 17,000

love letters. At age 77 she died in his arms, and although his sex drive continued during the remaining two years of his life, her death seemed to break his spirit at last.

QUIRKS:

Rumors abounded during his lifetime, as they have since, that he carried on an incestuous relationship with his daughter Léopoldine, but no conclusive proof of this exists. He was apparently a voyeur and something of a foot fetishist, and he was turned on by intrigue and mystery. He often admitted his mistresses through secret staircases and entertained them in hidden rooms even when this was not really necessary.

HIS THOUGHTS:

“Love … seek love … give pleasure and take it in loving as fully as you can.” And, to his young grandson, who walked in on the 80-year-old Hugo in the embrace of a young laundress: “Look, little Georges, that’s what they call genius!”

—R.W.S.

The Gay Romantic

The Gay Romantic