The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (48 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

Finally, he ran away with the 17-year-old poet Rimbaud. After an unsuccessful attempt to seduce her errant husband into returning home, Mathilde obtained a formal separation and eventually divorced him. It had been a mere three years from her first encounter with Verlaine to his final desertion.

RIMBAUD:

He was the evil boy-genius of French poetry, a beautiful, precocious teenager who wrote startlingly original verse, ascribing colors to vowels and feelings to inanimate objects. He was also, by all accounts, an insufferable hooligan, ruthlessly perverse, gratuitously sadistic. His philosophy of exploring every form of love, suffering, and madness in order to achieve poetic “truth”

made him sexual fair game for Verlaine.

Preceded by some of his poems and a letter of introduction sent to Verlaine, Rimbaud arrived in Paris dirty and penniless. Verlaine put him up at his in-laws’, where he was living at the time, then housed him with a succession of friends. (One of them, a homosexual musician, introduced the boy to the mind-expanding experience of hashish.) Day and night the two poets caroused, drinking and engaging in deliberately provocative displays of public affection.

Privately, Verlaine introduced Rimbaud to “nights of Hercules” and the exhilarating “love of tigers.”

Of the two, Rimbaud was clearly the dominant partner. Verlaine, who considered himself “a feminine” seeking love and protection, fell under the spell of the “infant Casanova” with his irresistible combination of beauty, genius, and

violence. Rimbaud, testing his powers, slashed Verlaine with a knife just to amuse himself, and taunted him about his marital respectability.

In July, 1872, the two poets ran away together, apparently with the financial assistance of Verlaine’s mother, who was jealous of Mathilde. “I am having a bad dream,” Verlaine wrote to his wife from Brussels. “I’ll come back someday.” Recovering, he invited her to join them: “Rimbaud would be very happy to have you with us.” The escapade lasted for the better part of a year, which Verlaine would forever remember as a time of “living intensely, to the very top of my being.” They explored the Belgian countryside, then crossed the channel to London, living in cheap hotels and rooming houses. They made a perfunctory effort to support themselves by giving French lessons, but were glad to fall back on Verlaine’s indulgent mother, who estimated bitterly that Rimbaud cost her 30,000 francs.

It was a period of great creativity for Verlaine. Rescued from bourgeois captivity, he wrote his

Romances without Words

. But it was also a time of constant bickering and vituperation, as Rimbaud vented his self-disgust and his hatred of being dependent on the older poet. Unable to bear it any longer, Verlaine left abruptly in July, 1873, for Brussels. Dispatching suicide notes to all concerned—including his wife—he waited to be rescued. Verlaine’s mother arrived first, followed by a truculent Rimbaud. In the drunken emotional disorder of the occasion, Verlaine turned his suicide weapon on Rimbaud, shooting him in the wrist. Threatened again and fearful of another attack, Rimbaud called the police, who arrested Verlaine and proceeded to investigate his sexual proclivities.

Medical examination revealed signs of homosexual intercourse. Verlaine was subsequently sentenced to two years in prison for attempted manslaughter.

Released in January, 1875—he got six months off for good behavior—

Verlaine sought out Rimbaud. The latter repulsed these advances by knocking him out and leaving him by the roadside. Rimbaud soon abandoned poetry and lived the rest of his short life as a mercenary adventurer, dying of cancer in 1891. Verlaine, never one to harbor a grievance, would remember their time together as the peak experience of his life—intellectually, emotionally, and physically—a time of pleasure so intense it bordered on pain.

SURROGATE LOVERS:

Verlaine spent the rest of his life divided between demon-lovers and mother figures, the opposite poles of sexual attraction for him. While teaching in a provincial school in 1879, he met a young student whose impudence and opportunism reminded him of Rimbaud. Lucien Létinois at 19 was a handsome and straightforward peasant. (A friend of Verlaine’s described him maliciously as a “musical-comedy shepherd.”) Lucien accepted the effusive affection and financial support of the 35-year-old poet, only to complain privately that he wished they had never met.

Verlaine maintained the sentimental fiction that Lucien was his adopted son. He took him to England and paid his expenses in London while he (Verlaine) taught at a private school in Hampshire. The poet later gave up his teaching post and rushed to London to rescue Lucien upon learning that he

had fallen in love with a young British girl. Then Verlaine bought a farm in France and installed Lucien’s family to help run it. The venture was a romance of rural life that ended in bankruptcy. When Lucien went into the army, Verlaine became a camp follower, composing fatuous verse about “the handsome erect soldier sitting his steed.” Yet Verlaine, fortified by his religious conversion in prison, seems to have stopped short of sexually seducing his “son.” When Lucien died of typhoid in 1883, the poet had him buried in a coffin draped in the white cloth indicative of a virgin. He then launched into a period of drunken homosexual vagabondage.

A young Parisian artist and writer named F. A. Cazals became for a time the poet’s platonic friend, heir, and obsession. Liberated by the death of his mother, Verlaine spent his last years—when not in the hospital—alternating between two aging prostitutes. Philomène Boudin and Eugénie Krantz were both slatterns who satisfied his adolescent craving for tainted sex and stimulated his masochism with their physical and verbal abuse. They were also greedy, urging him to write poetry which they exchanged for cash at his publisher’s office. Composed under the influence of absinthe and the broomstick, these poems reveal a preoccupation with thighs, breasts, and buttocks.

Philomène came equipped with a pimp, who extended his protection to the poet, but Eugénie, who was semiretired, provided him greater stability.

Eugénie was with Verlaine when he died and presided over his funeral in widow’s weeds. She soon drank herself to death with the proceeds from a lively trade in bogus literary souvenirs.

—C.D.

VII

Let’sMakeMusic

The Moody Bachelor

The Moody Bachelor

JOHANNES BRAHMS (May 7, 1833–Apr. 3, 1897)

HIS FAME:

Renowned as one of the

“three great

B

’s,” along with Bach and

Beethoven, Brahms is considered the

major orchestral and nonoperatic vocal

composer of the late 19th century.

HIS PERSON:

Brahms was raised in the

poverty-stricken red-light district of

Hamburg, and this environment left its

effects upon both his personality and his

love life. At an early age he played the

piano in taverns in order to earn money,

and most of his audiences consisted of

prostitutes and their clients. His mother,

a lame and homely woman, was 17 years

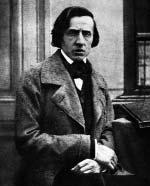

Brahms in his early 30s

older than his father, who was a timid

orchestral musician, and she lavished her affections on her young son. Maintaining an unnaturally strong attachment to her until her death in 1865, Brahms cried out over her grave, “I no longer have a mother! I must marry!”

This was not to be, however. He moodily vacillated between protecting his bachelorhood and considering marriage. An infinitely kind man who secretly supported struggling musicians when he was able, Brahms was also subject to fits of temper, and he was singularly lacking in tact and the social graces.

Although he enjoyed bawdy nights of beer drinking and folk songs, his music tended to reflect his darker side. While he was serving briefly as a conductor in Vienna, his programs were so invariably serious that people joked, “When Brahms is really in high spirits, he gets them to sing ‘The Grave Is My Joy.”’

His first few recitals brought him little public attention. But after his initial concert tour, at age 20, he met composer Robert Schumann in Düsseldorf, and Schumann was so greatly impressed by Brahms’ compositions that he recommended that they be published. Schumann also wrote about Brahms for a music magazine. His article created a sensation, and the young composer’s fame and reputation began to spread throughout Europe. Eventually Brahms adopted Vienna as his home, where he produced his four symphonies and the famous

German Requiem

.

LOVE LIFE:

As a lover, Brahms led a double life; he fell in love with numerous respectable women (always singers or musicians) but slept only with prostitutes.

One possible exception to this was Clara Schumann, the charming and beautiful wife of Robert Schumann. When Schumann suffered a nervous breakdown and was confined to a mental institution, Brahms stayed at Clara’s side. Her appeal as a mother figure (she had seven children) was combined with that of friend and musical adviser (she was an accomplished pianist). His feelings for her quickly deepened, as their correspondence shows. Addressed at first to “Dear Frau Schumann,” Brahms’ letters soon were being sent to a “Most Adored Being.” During Schumann’s confinement, the conflict Brahms felt between his friendship for Schumann and his passion for Clara made him so miserable that he gave only occasional concerts. He later described the mood of a quartet he started during this period as that of “a man who is just going to shoot himself, because nothing else remains for him to do.” When Schumann died after two years in the mental institution, however, the couple shied away from further romantic involvement. They remained close friends for the rest of their lives, and Brahms rarely published any music without Clara’s approval.

Brahms’ other affairs went much the same way. Unable to resist a comely figure or a beautiful voice, he had at least seven major, unconsummated relationships, but he always bolted before exchanging marriage vows. The objects of these romances often appeared in his music. After his affair with Agathe von Siebold, a fiery singer with lustrous black hair, he immortalized her in a sextet in which the first movement evokes her name three times by using the notes A-G-A-D-H-E (H is the German designation for B-natural). Another of his passions was Schumann’s daughter, Julie. When she became engaged to a count, the miserable Brahms presented her with his famous

Rhapsody

(Opus 53), a piece highly evocative of loneliness, and referred to it as

his

wedding song.

Yet he remained single. A fellow bachelor once remarked: “Brahms would not have confided to his best friend the real reason why he never married.” He may have been scarred by his relationship with Clara or by his strong attachment to his mother. His early exposure to the “singing girls” of Hamburg had certainly left its mark. He occasionally burst into tirades against women in general, and in an attempt to explain his behavior to a friend, he spoke of his early encounters with the tavern prostitutes: “These half-clad girls, to make the men still wilder, used to take me on their laps between dances, and kiss and caress and excite me. This was my first impression of the love of women. And you expect

me

to honor them as you do!” Always courteous to prostitutes, who found him an eager if awkward lover, his caustic side was more likely to surface with society women. In his relationships with women, Brahms liked to do all the wooing; he was put off if the object of his affection displayed any initiative. A flirtatious woman once asked him if he thought she resembled a famous beauty, and Brahms growled: “I simply can’t tell you two apart. When I sit beside one of you, I invariably wish it were the other!”

While he longed for domestic happiness and often complained bitterly of having missed the best part of life, Brahms continued to fall in love well into his 50s, only to abort the affairs before they threatened his bachelorhood, and he continued to immortalize his feelings in the rich, darkly passionate music for which he is known today.

HIS THOUGHTS:

HIS THOUGHTS:

“I feel about matrimony the way I feel about opera. If I had once composed an opera and, for all I care, seen it fail, I most certainly would write another one. I cannot, however, make up my mind to either a first opera or a first marriage.”