The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (90 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

12 of Young’s wives ever slept in the Lion House at the same time. A New England-style structure, it was connected by a corridor to the adjacent Colonial abode known as Bee Hive House. However, most of Young’s wives had their own private, monogamous-type residences scattered throughout the city.

The Lion House was the heart of Brigham Young’s harem. The second floor was sectioned into a central parlor for prayers and entertainment and a series of bedroom suites for wives with children. The third floor contained 20 smaller bedrooms for the childless wives and older children. When Young decided upon a bed partner for the night, he made a chalk mark on the selected wife’s door.

He fortified himself for each amorous visit by eating large numbers of eggs, which he believed enhanced virility. Later, he would quietly go down the row of doors, find the one with the chalk mark, and slip inside. Upon completing his husbandly duties, Young invariably returned to his own bedroom for a solitary night’s sleep.

His virility was never in doubt. He fathered 56 children. He had his first child, a daughter, when he was 24, and his last, also a daughter, when he was 69.

In a single month of his 62nd year, three of his wives gave birth to children. He had long sexual relationships with a number of his wives. Lucy Decker, the third wife, had her first child by Brigham in 1845 and her seventh by him 15 years later. Clara Decker, the sixth wife, had her first child by him in 1849 and her fifth child by him 12 years later. Emily Dow Patridge, the eighth wife, had her first child by him in 1845 and her seventh child by him 17 years later. Lucy Bigelow, the 22nd wife, had her first child by him in 1852 and her third child by him 11 years later.

SEX PARTNERS:

“I love my wives … but to make a queen of one and peasants of the rest I have no such disposition,” Young claimed. But many of his wives (along with other Mormon women) “whined” about his lack of attention, and Young responded by offering to divorce any of them that so wished. None did at that time. Certainly, however, Young had his favorites, and for nearly two decades Emmeline Free was his chief lover. They wed when she was 19 (and he 44), and over the years Emmeline bore him 10 children. She was, the other wives whispered, awarded the best quarters—a room that featured a private stairway Young could secretly use for his frequent visits.

But Emmeline’s reign ended soon after 1860 with Young’s first sight of Amelia Folsom, a 22-year-old who stubbornly resisted his advances and announced her love for another man. However, that rival stepped aside when threatened with a lengthy church mission, and Amelia surrendered to Brigham’s wishes. But not fully. Unlike Emmeline, Amelia relished her role as Young’s favorite. When he gave her a sewing machine, she pushed it down the stairs; it was the wrong brand, she huffed. Young bought her the right brand. When he lectured her on her sins, she scoffed, and on one occasion punctuated his sermon by pouring a pitcher of milk and an urn of hot tea on his lap. Never one to tolerate disobedience from anyone, Young nonetheless suffered it from Amelia until his death.

Troublesome as Amelia proved, it was Ann Eliza (wife number 27 by some counts; 51 by others) who proved the most rebellious. This wife, too, rejected the aging Young’s advances. “I wouldn’t have him if he asked me a thousand times—hateful old thing,” she told friends. But she underestimated Young’s determination; in 1869, a year after the courtship commenced, the 24-year-old bowed to family pressure and married him. But Young got more than he bargained for. Ann Eliza complained about his inattention; castigated him for his frugality (despite his riches, Young doled out slender provisions to his wives); and, in 1873, listing neglect and cruelty among the causes, she escaped Salt Lake City and filed for divorce. Young found himself forced to contest her claim strenuously, for only a year earlier federal charges of polygamy had been dropped because of a technicality. By conceding that Ann Eliza could sue for a divorce, Young would be admitting that he was a polygamist, and the federal government, he was sure, again would pounce on him. After years of bitter legal wrangling, Young won his case. He told the court that he was legally married to Mary Ann Angell (his second wife and his senior living spouse) and that he could not, therefore, have legally married Ann Eliza. But, in splitting this legal hair, Young had in effect repudiated his cherished doctrine of polygamy—a practice that soon after his death was to be formally abandoned by the Mormon Church.

HIS THOUGHTS:

“Some want to marry a woman because she has got property; some want a rich wife; but I never saw the day I would not rather have a poor woman. I never saw the day that I wanted to be henpecked to death, for I should have been if I had married a rich wife.”

“Make haste and get married. Let me see no boys above 16 and girls above 14 unmarried.”

—R.M.

XV

Heads YouWin

PSYCHOLOGISTS

The Impotent Educator

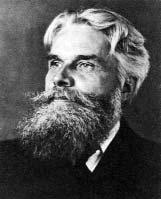

HAVELOCK ELLIS (Feb. 2, 1859–July 8, 1939)

HIS FAME:

Called “the Darwin of sex,”

Havelock Ellis was principally known as a

sex educator and the author of a seven-volume work issued between 1897 and 1928

entitled

Studies in the Psychology of Sex

.

HIS PERSON:

The son of a sea captain

and a doting mother, Ellis was born in

Croydon, Surrey, England. He attended

private schools in London. At 16, suffering poor health, he was sent to Australia

on his father’s ship. There he worked as a

teacher—part of the time in remote

areas—for four years, too shy to be effective. Returning to London, he entered

St. Thomas’ Hospital at 22 to take up

medicine. After graduation, he practiced briefly in the London slums. Because he loved books, he gave up medicine for literary pursuits.

At 30 he published his first book,

The New Spirit

. Shortly after, Ellis became interested in sex, then a forbidden subject. Through interviews and research reading, he gathered material on human sexuality and wrote about it. The first volume of his

Studies in the Psychology of Sex

series was entitled

Sexual Inversion

and dealt with homosexuality. The book was banned in England for “obscene libel.” Nevertheless, Ellis continued to pour out books about various aspects of human sexuality. Although widely known, he lived close to poverty most of his life. He was 64 when he had his first commercial success with

The Dance of Life

, an immediate hit in the U.S.

During his lifetime, Ellis defended the rights of women and homosexuals, and pioneered open discussions on sex. He gave free advice on sex to anyone who wanted it, and he could not understand why Sigmund Freud charged patients for the same help. Ellis was a sweet and humane man, part scientist, part mystic. Birth-control crusader Margaret Sanger found him a “tall angel,” blue-eyed, handsome, with his trademark flowing white beard. He died in Washbrook, Suffolk, of a throat ailment at the age of 80.

SEX LIFE:

Not until he was 25 did Havelock Ellis have any sexual experience with a woman. It came about by accident. He had read a novel,

The Story of an

African Farm

by Ralph Iron, and wrote a fan letter to the author. The author proved to be an attractive, lusty woman named Olive Schreiner, a 29-year-old feminist and well-known novelist. They corresponded and then they met. Olive, who wanted to be dominated, expected a strong man and found in Ellis an awkward and withdrawn intellectual. They became friends, and he gave her his daily journal to read. Going through it, she realized that he was totally inexperienced in sex. Olive, who’d had several affairs with men, decided she could rectify that and eventually marry Ellis. She lured him to the Derbyshire countryside for a weekend. During their first walk together, she put her hand on his crotch to feel his penis. Determined to consummate their love, she lay nude with him on a sofa. He caressed her and kissed her vagina. He could not get an erection and finally suffered premature ejaculation. Time and again they tried, with the same result. “She possessed a powerfully and physically passionate temperament,” Ellis admitted, and he could not match her sex drive. They settled for a close and enduring friendship. She was ever uninhibited with him.

Once, in Paris together, observing some bronze vessels in the Louvre, Olive spoke seriously of the handicaps women suffered. “A woman,” she said, “is a ship with two holes in her bottom.” Eventually Olive returned to South Africa, married a farmer-politician, and endured a less than successful marriage.

Havelock Ellis was 31 when he became involved in his greatest love affair.

Edith Lees, a 28-year-old former social worker, was curly-haired, pretty, under 5

ft. tall, and outspoken. Edith was drawn to Ellis upon reading his first book. He in turn liked her brightness and intelligence. When she proposed marriage, he worried about his privacy and his low financial state. Edith promised him privacy and agreed to share all their expenses. (She was running a girls’ school at the time.) They went out for a wedding ring, and she paid for half of it. The marriage took place in December, 1891.

Edith did not know Ellis was impotent. On their honeymoon in Paris she found out. He did not even attempt to have intercourse with her. While she had told Ellis she’d had affairs with several men, she had not told him she liked women more. Edith mourned the baby she could never have with Ellis and settled for his fondling her in bed, still thinking him “beautiful” and her spiritual lover. She agreed to a marriage of companionship, but not for long. Three months after their wedding, she informed him that she was having a torrid affair with a woman named Claire. Unhappy but tolerant, Ellis interviewed Edith on lesbianism for a book he was writing on homosexuality. After breaking with Claire, Edith had another affair with a fragile painter named Lily. When Lily died, Edith turned her attentions back to her husband.

Their 25-year marriage was a stormy one. It turned out that Edith was a manic-depressive. When manic, she fixed up and rented cottages, gave lectures as Mrs. Havelock Ellis (her favorite lecture was on Oscar Wilde), wrote books and plays, and founded a film company. When depressed, she sat at her female lovers’ graves, had several nervous breakdowns, and three times tried to commit suicide. When she resumed her lesbian affairs, Ellis continued to love her and resumed his own sexless affairs. He outraged his wife when he fell in love with the 24-year-old daughter of a chemist friend, a woman he referred to as Amy (her real name was Mneme Smith) and continued to be close to until she married another man. He was 57 when he met and became enchanted by Margaret Sanger. This intimate relationship brought Edith back from a lecture tour in the U.S. and gave her one more nervous breakdown. Ellis was constantly attentive to Edith. Her doctor told him she was on the verge of insanity. In September of 1916 she died in a diabetic coma.

Shortly afterward, a charming young Frenchwoman, Françoise Cyon, entered Ellis’ life. Françoise wanted to collect her fee for having translated one of Edith’s books into French. Drawn to Ellis’ kind understanding, she returned to him for marital advice. She’d had a child by an earlier lover, and a second son by her husband, Serge Cyon, an insensitive Russian journalist whom she had recently left. During her treatment by Ellis, Françoise fell in love with him. On April 3, 1918, she wrote him, “I am going to write a very difficult letter. Yet it must be written if I want to find peace of mind. The truth is, Havelock Ellis, that I love you.” He tried to warn Françoise of his impotency. He wrote her that he had many dear women friends. “But there is not one to whom I am a real lover…. I feel sure that I am good for you, I am sure that you suit me. But as a lover or husband you would find me very disappointing.” Puzzled, she replied, “I will have nothing but what you offer; it is the very flower of love.”

On going to bed with him, she learned his problem but was undeterred.

They masturbated each other. She lavished love on him unconditionally, treating him as a virile male, a potentially good lover. And miracle of miracles, he responded. Aged 60, he had his first erection with a woman, and then another and another, and found himself enjoying sexual intercourse at last.

Their relationship was idyllic, marred by only one bad incident. Ellis had asked her to be friendly with one of his admirers, an urbane minor novelist and advocate of free love named Hugh de Selincourt. While Ellis was out of town, Françoise allowed De Selincourt to seduce her. He was a mighty lover. He hated to wear a contraceptive device and had trained himself to copulate at great length, bringing his women to orgasm without ejaculating himself.

Françoise lost herself in pleasure. Then Ellis learned about the affair and was wounded, feeling she had found a younger and better lover. Françoise tried to gloss over the physical aspect of her affair. Ellis answered, “Do you imagine that coitus is unimportant? Olive said to me once that when a man puts his penis into a woman’s vagina it is as if (assuming of course that she responds) he put his finger into her brain, stirred it round and round. Her whole nature is affected.” Françoise pleaded with Ellis, writing him, “You have been the beloved, the lover, the friend most divine. You are still this, will always be.” She gave up De Selincourt and returned to Ellis. She worked as a teacher and at first lived separately with her sons. She wanted to move in with Ellis, but he could not support her. Then, from America, Margaret Sanger offered her a salary as Ellis’ secretary. Françoise, at last able to pay her share of their expenses, joined