The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (15 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

This inaugurated a new era in the exploitation of print. In the course of the sixteenth century the state became one of the most important patrons of the publishing industry. Official publications of one sort or another became a staple of the industry. In many provincial cities the demands of local and national government for printed ordinances and regulations helped maintain a local printing press that would otherwise scarcely have been viable.

The success of these experiments led to something altogether more ambitious. Could print be used, not only to inform, but to persuade? Could print become a powerful instrument for explaining policy and shaping public opinion? It was not long before Europe saw the first sustained campaigns of state-sponsored polemic. This was a development of huge significance for the history of the news.

Patriot Games

We can see that the propaganda potential of print had not been lost on Maximilian. Having been humiliated at Bruges, he was keen that sympathetic printers elsewhere in his dominions would laud his policies as well as circulate his instructions. The publication of treaties was always an opportunity to advertise the virtues of peace, and praise the wisdom and magnanimity of the great. But for the most systematic exploitation of the press by the state to mobilise public support we should look not to Germany or Italy, the two largest and most developed news markets of the Renaissance era, but to France. At the end of the fifteenth century France was a powerful state emerging from 150 years of chronic warfare and political division. At times during the Hundred Years War the portion of French territory acknowledging the authority of the king had shrunk to a rump in central France; after the battle of Agincourt in 1415, even Paris had briefly been occupied by the English. The expulsion of the English in 1453 was a turning point; thereafter the French Crown consolidated its territories through the incorporation of important fiefdoms in the west and south. By 1490 France was an exceptionally coherent and potentially wealthy state of some 12 million inhabitants.

To celebrate this new national awakening French kings were able to draw on some of the most gifted writers in Europe. The circle of poets and chroniclers who followed the court had already been put to good use in some precocious campaigns of political writing at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

3

This established habit of literary advocacy could easily be adjusted to the age of print. And here the French possessed a priceless weapon, because in Paris they had at their disposal one of the greatest and most sophisticated centres of early print culture. In the fifteenth century this had been orientated mostly towards the publication of scholarly and Latin books. Now it would be used to engage the French public in the Crown's ambitious plans for territorial conquest.

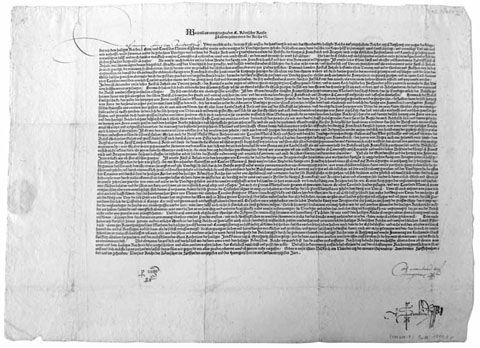

4.1 Print in the service of officialdom. In summoning a meeting of the German Estates, Maximilian gives a detailed account of recent events, including the battles of Verona and Vicenza.

In seeking to exploit their new-found unity and strength, French eyes had turned inevitably to Italy. In 1494 the French claim to the kingdom of Naples led Charles VIII to embark on the first of a long series of military interventions that would, in the next sixty years, bring much tribulation to the Italian Peninsula, and ultimately little glory to France. From the beginning the military campaigns were accompanied by despatches home chronicling French progress and lauding their victories. A flurry of printed pamphlets shared news of the king's entry into Rome, his audience with the Pope, the conquest

of Naples and Charles's coronation.

4

These were all short pamphlets of four or eight pages, sometimes embellished with an eye-catching title-page woodcut. Most were the work of Parisian printers, though a number seem also to have been published in Lyon, a natural intermediary point for returning news on the road to the capital.

The pamphlets of the Italian campaign were not absolutely the first of this genre to appear on the French market. In 1482 the treaty concluded between Louis XI (Charles VIII's father) and Maximilian had been published as a pamphlet.

5

The printing of treaties became a staple of official publications, if necessary with some judicious editing of the more controversial clauses to ensure a favourable reception. This was certainly the case with the Treaty of Étaples, concluded between Charles VIII and Henry VII of England in 1492. Rapid shifts of royal policy needed careful and sympathetic handling, and the French Crown could call on a number of distinguished writers to make the case for peace, or war, as the occasion demanded. In 1488 Robert Gaguin called for peace with England in his ‘Passetemps d'oisiveté'; four years later Octavien de Saint-Gelais supported the renewal of war in a poem advising the foreign troops that they would be ‘better off back in Wales drinking your beer’.

6

Some of these effusions circulated in manuscript, others in print. Sometimes the propaganda effort overflowed onto the stage. We see some of the most imaginative use of regime-friendly propaganda during the reign of Louis XII, who in 1498 had rather unexpectedly inherited both the French throne and Charles VIII's claims in Italy. The outpouring of news pamphlets reached its high point with Louis's campaigns of 1507 and 1509, which brought about first the suppression of the rebellion of Genoa, then the humbling of Venice by the League of Cambrai.

7

Louis's success provoked a counter-alliance determined to limit French power, led by the irascible warrior-pope Julius II. The bitter and very personal feud that now erupted between Louis and Julius was accompanied by a sustained campaign of personal denigration. A wave of political treatises and poetry engaged, among others, the talents of Jean Lemaire de Belges, Guillaume Crétin and Jean Bouchet. A printed placard carried a caricature of the Pope lying prone beside an empty throne and surrounded by corpses; a early example of political caricature. Pierre Gringore, the most talented of contemporary playwrights, staged a newly written

sottie, Le jeu du prince des sotz et de mère Sotte (The Game of the Prince of Fools and his Idiot Mother

). Full of cutting ridicule of Julius, this was performed at Les Halles, the main marketplace of Paris, on Mardi Gras in 1512.

8

If this was a treat for the citizens of the capital, it was printed pamphlets that ensured the widest possible circulation in the nation as a whole. In all we can enumerate at least four hundred news pamphlets published in French during

the period of the Italian Wars (1494–1559).

9

The truly innovative character of this literature can best be appreciated if we contrast this French use of print with the public reaction to the French assault in Italy itself. The French descent into Italy was a cataclysm for the Italian states. The sophisticated mechanism of communication developed to keep the rulers of the Italian states abreast of events helped generate an ever-shifting pattern of alliance and antagonism between the rival powers. It offered little protection against a ruthless external foe. As the most vulnerable Italian cities marshalled inadequate defences, others sought to pursue their hopes of territorial gain by allying with the invader. The result was chaos.

The news networks of Renaissance Italy had been developed to serve the needs of a closed political and commercial elite. Now, in a time of crisis, the limitations of this culture were laid bare.

10

The division between the rulers and an alert, articulate people was nowhere more obvious than in Florence. The great city of the Medici had shown little enthusiasm for the printing press. Now it paid the price as the thunderous prophecies of Savonarola captured a rapturous audience, first for his preaching, then for subsequent printed versions. Florence's under-appreciated printers, starved of patronage, were naturally delighted to find a new audience.

11

In Venice, Rome, Milan and elsewhere the writers of Italy turned away from demonstrations of polished humanist eloquence to an outpouring of vituperative political commentary. The poetry of the years of the French invasions is charged with a vivid savagery, as Italy's poets lamented the consequences of selfish and short-sighted political divisions, the hypocrisy of Church leaders, the vanity of princes, and the worthlessness of treaties and alliances. Little of this made its way into print; most was circulated in manuscript or posted anonymously in public places. From 1513, and the election of the Medici Pope, Leo X, this political poetry took on a pointedly personal tone. Leo and his successors, and indeed the entire college of cardinals, were denounced for a catalogue of vices.

Seen in the round this literature of denunciation makes clear the hopelessness of Italy's predicament. The contrast between the optimistic, celebratory literature orchestrated by the French Crown and the utterly negative and destructive tone of the Italian pasquinades (satiric verses) is very striking. The political poetry of Rome, though witty and carried along by a torrential energy, was inward-looking and parochial. It may well have been that Cardinal Armellini had a mistress, but would Rome have been better defended, and the Church better governed, had he been chaste? The smallness of these concerns and their mean-spirited nature made it difficult to see beyond this world of gossip, manoeuvres and tiny victories towards any real solution of Italy's

predicament. This would be the fate that would await many satirists in the centuries that followed: the impotent glee of enraging the great, momentarily diverting, but ultimately changing nothing.

The Fog of War

The bitterness of these internecine conflicts in Italy and the conservative tradition of Italian letters made impossible the effective use of print such as we have seen in the case of France. The first to follow the French into the realms of political propaganda were not therefore the sophisticated Italians, but their Habsburg adversaries. With his election as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, Charles V had fulfilled the elaborate dynastic plans of his grandfather Maximilian in the most spectacular way. France was encircled by a suffocating mass of Habsburg territories. The struggle for supremacy was fought in an exhausting sequence of campaigns and battles, a conflict that also had a profound echo in a coordinated effort to shape the news.

The ebb and flow of pamphlet warfare mirrored closely the rhythms of the conflict. French campaigning in Italy produced a flurry of publications in 1516 and 1528–9. On the imperial side the interconnected events of 1527–9, with the coronation of Ferdinand I as King of Hungary closely followed by the renewal of the French War, produced a comparable outpouring of news prints in the Netherlands. Here Antwerp was in precisely these years emerging as Europe's northern news hub, and a major centre of print. More than thirty printers there helped chronicle the Emperor's determined efforts to humble France.

12

Needless to say, both sides were keener to celebrate success than to acknowledge reverses. Charles V's loyal subjects would read of the king's great triumph at Tunis in 1535, but not of the catastrophe at Algiers six years later. It was the French who chose to publicise the scandal of the sack of Rome in 1527, laid waste by imperial troops under the French defector, the Duke of Bourbon. Netherlandish printers preferred to reserve comment until the Emperor's triumphant entry into Rome in 1536 provided them with a more palatable subject.

The climax of this polemical ping-pong came in the years 1542–4, a period of intense diplomacy concluded by simultaneous war in several theatres. In 1538 Charles V and the French King Francis I had been temporarily reconciled following a peace treaty painstakingly brokered by the Pope. Francis now faced the delicate task of explaining to the politically informed in his nation why a reviled adversary was to be welcomed to French territory as the Emperor journeyed from Italy to the Low Countries, feted in lavish civic receptions at every step. Once again the literary men did their duty: Clément Marot celebrated Charles as a new Julius Caesar, this time come to Gaul in peace. France's

printers, meanwhile, offered fascinated accounts of the Emperor's reception in Orléans and Paris. By 1542, however, the fragile reconciliation was in tatters. The French declaration of war was published as a pamphlet in four French cities: Paris, Troyes, Lyon and Rouen.

13

The beginning of a provincial culture of printed news was a new development in these years. The recent discovery of a large cache of pamphlets published in Rouen between 1538 and 1544 allows us to reconstruct it in unexpected detail.

14

The Rouen pamphlets were very rudimentary works: all in a small octavo format, seldom more than four pages long. But they offered local readers in this important regional centre the opportunity to follow the progress of the struggle in surprising detail.