The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (35 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Such commercial skulduggery reflected a perception at least that there was money to be made in newspapers. As Germany became for an extended period in the seventeenth century the fulcrum of European politics, the circles of those who felt they needed to keep abreast of the news grew ever wider. The urgency of events made for rich pickings in Germany's dispersed and disparate reading communities. It was far easier to start a new paper, repeating news passed along the postal routes, than it was to import papers published elsewhere. But the elastic market and easy profits also served to reinforce the conservatism of the genre. The German newspapers of the later seventeenth century were remarkably little different in content or design from the earliest ventures. It would be in other parts of Europe that the most significant experiments of design and composition were seen.

The explosion of news print was, for all that, highly significant for the development of the European news market. It marked a very significant reorientation of the European news world towards northern Europe. Up to this point the exchange of news had been dominated by the connection between the Mediterranean and the Low Countries, linked by the arterial route of the imperial post road. But the most important centres of newspaper production in Germany were far removed from the old imperial postal route: Augsburg, the German axis of the imperial postal network, spurned the newspaper revolution. Elsewhere in Europe, too, it was the northern powers that eagerly embraced the new invention. The centre of gravity of European information exchange had shifted decisively.

Stop Press

The first newspaper to be published outside Germany appeared in Amsterdam in 1618. Here, too, the industry would develop very rapidly.

14

In this period the newly independent Dutch provinces were concluding their swift progress to the first rank of European powers: Amsterdam would be the dynamic heart of this new economy. The city now inherited the economic and political hegemony enjoyed in the previous century by Antwerp and Brussels (which remained under Habsburg rule). Within two decades Amsterdam had also established a clear supremacy as the centre of the west European news market.

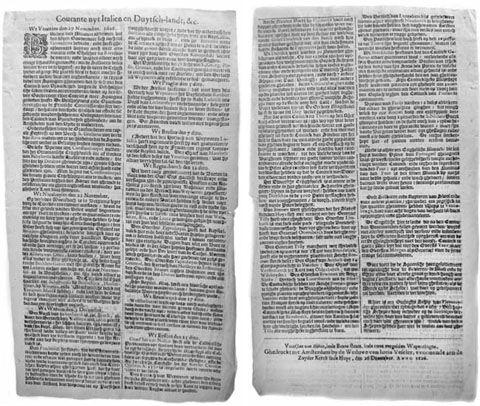

The first Dutch newspaper was a comparatively modest affair: a single broadsheet printed on one side only, with the news in two columns. In design terms this represented a significant departure from the German pamphlet form, though the news included in Jan van Hilten's

Courante uyt Italien en Duytsland

would have been utterly familiar. As in the German prototypes each sequence of reports was announced by a heading indicating the place of origin and date of the despatch: ‘From Venice, 1 June'; ‘from Prague, 2 ditto'; ‘from Cologne, 11 ditto’. The issue concluded with a brief digest of news gathered from The Hague (here dated 13 June); presumably the sheet was published the next day.

15

Van Hilten's concept proved extremely influential: the broadsheet in two columns became the prescriptive form for early newspapers in the Dutch Republic. In 1620 the mounting quantity of news obliged van Hilten to extend over to the reverse side of the sheet, but this generally proved sufficient. By this point he already faced competition. In the lively and loosely regulated book world of the United Provinces there was no question of a monopoly; already by 1619 Broer Jansz had set up his

Tijdinghen uyt verscheyde Quartieren

(

Tidings from Various Quarters

). Jansz was an experienced printer who had dabbled in contemporary history; he was also well connected, as he emphasised by styling himself ‘couventier’ to the Prince of Orange in the first surviving issue of his paper. For ten years van Hilten and Jansz shared the market. It was clearly lucrative; by 1632 van Hilten found it necessary to set up simultaneously on two presses to double the print run. In this way he could print more copies without extending printing time by a day, and thus risk missing the latest news.

16

Late-arriving news was a perennial problem for publishers. However early on the day of publication they roused their workmen, it still took several hours to print several hundred copies, one pull at a time, and then the sheets needed some time to dry before the reverse leaf could be printed. The problem was only exacerbated as print runs grew larger. So when news came very late, van Hilten would stop the press and rearrange the text, deleting a story of lesser

importance. If the new report required more space, he would either make further small adjustments or set the new text in smaller type.

17

Thus was the principle of ‘stop press’ invented.

9.2 The first newspaper in the Netherlands. Unlike the German prototypes, both Amsterdam news men adopted a broadsheet format.

From Amsterdam it was perfectly possible to distribute news-sheets over the whole of Holland, using the province's extremely efficient canal-boat network. Not surprisingly, though, other printers in the United Provinces were equally keen to take a share in the market. In 1623 a paper was established in Delft. This, however, was not what it seemed. A comparison of a weekly issue of the Delft news-sheet of 10 May 1623 with that of Broer Jansz two days before shows that 90 per cent of the Delft reports were lifted unaltered from the Amsterdam paper.

18

The first truly independent enterprise outside Amsterdam was established at Arnhem, near the German border. Here the local printer was encouraged to start a paper by the town council, who obligingly resolved to cancel their subscription for a manuscript news-service from Cologne and instead paid Jan Janssen 20 gulden a year to print

one. This was generous. Janssen rose to the challenge and his was the first newspaper in the Netherlands to be printed with sequential numbering.

In Amsterdam the rage for news showed no sign of abating. By the 1640s the city sustained no fewer than nine competing titles: a news aficionado could find fresh news available on four days of every week.

19

Such competition encouraged a degree of innovation. The Dutch papers were the first to include advertisements. The Amsterdam papers also included, as the last substantial report before the advertising material, a section of news furnished locally. This was not in any genuine sense domestic news: rather it gathered up news from France, England and, from 1621, news from the front in the renewed conflict with Spain. This was relayed in a curiously dispassionate tone; there was little sign of the political debate raging in the contemporary pamphlet literature. This reluctance to be drawn into domestic politics was entirely typical of the early newspapers. Parochial affairs intruded only in the advertisements and public notices inserted by the municipality: the promise of reward for the return of stolen goods, the description of a wanted criminal. Here, for the first time, the newspapers descended truly to the level of the local.

20

While the Amsterdam papers thus made tentative steps towards the accommodation of a broader range of materials, the larger proportion of space was devoted to the usual diet of battles, treaties and diplomatic manoeuvres.

21

The ordering of materials followed a traditional sequence, with news from Italy preceding news from the Empire and elsewhere. In this respect the Dutch folio sheets followed the German prototypes in sticking close to the template of the manuscript newsletter. For true innovation, which offered an attractive alternative vision of the future of news publication, we need to call in at the shop of a little-known figure from the southern Netherlands, Abraham Verhoeven.

Tabloid Values

Before he plunged into the market for current affairs Verhoeven had eked out an existence on the margins of the Antwerp book world.

22

While the firm of Plantin occupied its palatial buildings on the Vrijdagmarkt, Verhoeven sold his more modest merchandise, pamphlets, almanacs and prayer cards, from a shop in the Lombardenvest, a part of town inhabited by pawnbrokers and other small businesses. What propelled Verhoeven into the front rank of Antwerp's affairs was his attempt to exploit the heightened interest in current affairs in the early years of the Thirty Years War by creating a new topical serial devoted to publicising German and other international events.

Verhoeven was born into the trade; his father was a cutter of prints, who for three years worked in the Plantin workshop colouring engravings before they

went on sale. After a long apprenticeship Abraham got his first major break as an independent artisan in 1605, when he offered on the market an illustrated print of the battle of Ekeren, a decisive victory for the southern Netherlandish forces over the marauding Dutch.

23

Verhoeven seems then to have survived mostly on jobbing work until 1617. In that year we see the beginnings of something more systematic and ambitious, with the publication of a sequence of pamphlets that combined a digest of topical news with a rudimentary illustration.

By now Verhoeven had developed the concept that would give him a dominant place in the Antwerp news market. It would blend his new activity as a publisher of news pamphlets with his established expertise as an engraver. But he was determined not to be undermined by competitors, or imitators: like Carolus in Strasbourg before him, Verhoeven appealed to the authorities for a privilege (or monopoly). On 28 January 1620 this was granted; Verhoeven was to have the exclusive right to publish news-books in Antwerp, or, as the privilege expressed it, ‘all the victories, sieges, captures and castles accomplished by his Imperial Majesty in Germany, Bohemia and other provinces in the Empire’.

24

This, in a nutshell, encapsulated Verhoeven's mission. His

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

would be a deliberate departure from the sober, neutral tone of the Amsterdam and German newspapers: essentially a propaganda vehicle for the local Habsburg regime. Verhoeven offered his readers up to three eight-page pamphlets a week: a torrent of wickedly committed, exultant reports of imperial victories and Protestant humiliations. These were not the sober miscellanies that German readers would expect for their weekly subscription. Verhoeven's pamphlets very often gave the whole issue to a single extended report, in the old pamphlet style.

It took Verhoeven a little time to arrive at a product with which he was entirely satisfied. In the early years we can see him experimenting with the best means of luring and keeping his audience. In 1620, the year he received his privilege, Verhoeven issued 116 news pamphlets: this year, we must assume, marked the beginning of his subscription service. But it was only in 1621 that he decided to make the pamphlets part of a numbered sequence, and to incorporate this numbering into the top of the title-page. By this time, too, Verhoeven had established the distinctive character of his news serials. They were distinguished, firstly, by a great deal more stylistic variety than the Dutch and German newspapers. Some issues of the

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

were, like other newspapers, given over to a miscellany of small items. Others were entirely occupied by a single despatch, or a couple of songs celebrating some imperial triumph. Publishing three times a week gave Verhoeven considerable freedom to entertain as well as inform his subscribers, but over the week they

would probably have got much the same amount of news as subscribers to the Amsterdam papers. By giving up space for a title-page, and often repeating in full the privilege on the back page, Verhoeven greatly restricted the space for actual news: in any one issue the whole text would not exceed around 1,200 words. It was short, lively and easily digested.

Verhoeven's most distinctive innovation in the new world of newspapers was the illustrated title-page. The title for the issue of 16 December 1620, inevitably focusing on the events of the Thirty Years War, reads: ‘News from Vienna and Prague, with the number of the principal gentlemen fallen in the battle’. The illustration bears the explanatory rubric, ‘The fort of the Star where the battle was fought’. The sub-heading drives home the message of this Catholic victory: ‘Frederik V has been driven away’.

25

But for the heading declaring this to be part of a serial, it could have been one of the Antwerp news pamphlets published fifty years before, with its descriptive title, sub-title and jaunty woodcut. The title picked out the story most likely to interest readers – the origins of the headline – but this would not necessarily be the first report in the text, nor indeed the story that occupied most space. Thus the headline of issue 112 of 1621 focused on the burial of the recently slain imperial General Busquoy.

26

But readers would have discovered this only as a small report on page seven. The issue begins with a despatch from Rome, and proceeds through an earlier report from Vienna, then Wesel, Cologne and Cleves, before arriving at the Vienna despatch dealing with Busquoy. Nor was the woodcut illustration a particularly clear steer to the most important contents. In this case the illustration was a generic bastion fortress rather than a portrait of Busquoy (although Verhoeven had a variety of such portraits that he used many times).