The Invitation-Only Zone (9 page)

Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

Until the late seventies, the abduction project was an all-Korean affair. North Korean troops had occupied and retreated from Seoul twice during the Korean War, each time taking thousands of southerners with them. As Kim Il-sung explained in his 1946 decree “On Transporting Intellectuals from South Korea,” the goal was to bring five hundred thousand people

to the North to compensate for the exodus of professionals—bureaucrats, policemen, engineers—who fled in the years leading up to the war. There was nothing random about the operation. “North Korean soldiers with long lists of names went from house to house looking for specific men to take with them,” remembers Choi Kwang-suk of the Korean War Abductees’ Family Union.

2

Choi’s father, a high-ranking

policeman, was on one list, and the ten-year-old never saw him again. It is estimated that the North took eighty-four thousand South Koreans in all, sixty thousand of whom were inducted into its army. Although the number of abductions decreased dramatically after the Korean War, they never entirely stopped. The Korean Institute for National Unification reports that four thousand South Koreans,

mostly fishermen, have been abducted since 1953. This includes five high school students abducted in 1977 and 1978 and a teacher snatched while on vacation in Norway in 1979.

The majority of those taken in the twenty-five years after the Korean War were fishermen. In the days before GPS technology, ships often drifted over the “Northern Limit Line,” a water-borne demilitarized zone whose precise

location the two Koreas have never agreed upon. Hundreds of fishing vessels were boarded by the North Korean navy and towed back to port. The abductees were welcomed to the socialist paradise and treated with the kind of respect that illiterate laborers seldom received in the South. Lee Jae-geun, a fisherman who was abducted in 1970, told me about the hero’s welcome he received.

3

Upon disembarking

from his ship, he was greeted by six women loaded down with flowers. “Don’t go back to the South! Come live with us in the earthly paradise of the North,” they begged him. Most of the abducted fishermen were returned after a few weeks or months, with the hope that they would talk about how well they had been treated, and spread the word about the higher living standards then enjoyed in the North.

A few chose to stay in the North voluntarily, convinced (perhaps correctly) that poor fishermen would lead a better life in a socialist than in a capitalist country. And the North Koreans were always on the lookout for exceptional men who, despite their lack of formal education, had the kind of raw intelligence that might be of use. Many, including Lee Jae-geun, were recruited and trained to

spy on the North’s behalf. Most were returned to South Korea, and a few, like Lee Jae-geun, escaped. Five hundred South Korean abductees remain in the North today.

The abduction project matured during the period when Kim Jong-il was rising to power. In February 1974, Kim Jong-il was elected to the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, an event that marked his ascension to his father’s

position. Proving his worth was not as easy as many assume. Kim would often arrive to Politburo meetings late or hungover, only to be berated by his father in front of the senior leadership.

4

As part of his new portfolio, he ran the regime’s intelligence service, and it didn’t take long for him to conclude that it needed upgrading. Kim was particularly bothered that several North Korean spies

had confessed after being captured, instead of committing suicide as instructed. Others had betrayed the regime by accepting bribes from foreign intelligence agencies. It was time to clean house. One by one, he recalled spies from around the world, putting them through drills and weeding out those he deemed unfit. Dozens were either executed or sent to the regime’s far-reaching gulag. To replace them,

Kim recruited an army of elite spies, handpicked from the best schools and universities, loyal to him alone.

The world in 1974 was a more complex place than the one his father had faced in 1948. Kim diversified and expanded intelligence operations, abducting native teachers to train North Korean spies to navigate the languages and cultures of Malaysia, Thailand, Romania, Lebanon, France, and

Holland. Among the reasons Japanese nationals were abducted was to steal identities with which to create fake passports. The targets tended to be unmarried low-status men who lived far from their families and wouldn’t be missed. Japan’s traditional family registration system (

koseki

) had yet to be fully centralized in the late seventies, so there was no reliable national database against which

a forged passport could be compared. And a Japanese passport granted the holder access to virtually any country on earth.

* * *

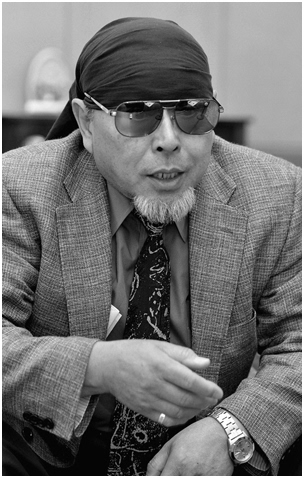

“Thank you for coming, Madame Choi. I am Kim Jong Il.”

5

Choi Eun-hee, South Korea’s most famous actress, felt a sense of terror the moment she heard his name. It was January 28, 1978, when Choi’s boat entered the port of Nampo, on North Korea’s western coast. A

week earlier she had flown from Seoul to Hong Kong to discuss a project with an acting school she had been running since the closing of Shin Films, the studio she ran with her husband, the director Shin Sang-ok. The meeting, it turned out, was a ruse to lure Choi into the hands of her North Korean captors. Kim Jong-il reached out to greet her. “I didn’t want to shake hands with the man who had engineered

my kidnapping, but I had no choice,” she writes in her memoir. At the moment they shook hands, a cameraman popped up to take their photo. “I didn’t want any record of that moment. Nor did I want any long-lasting proof of my unkempt and ugly state.”

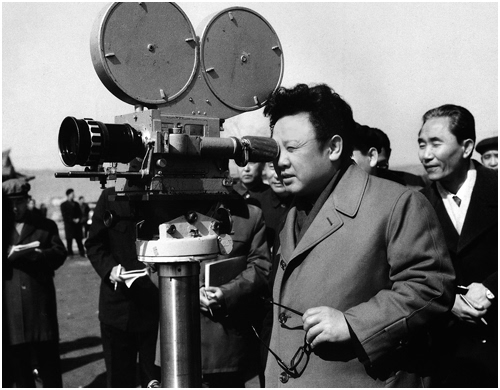

Kim Jong-il with camera

(Associated Press)

Three weeks after Choi disappeared from Hong Kong, Shin went looking for her. Although they had divorced two years earlier, they were still extremely close. He had warned her that the invitation to Hong Kong seemed suspicious, and he was now determined to rescue her. Often called the Orson Welles of South Korea, Shin had made three hundred movies at

Shin Films, the country’s largest studio, before running afoul of President Park Chung-hee. At the time of his ex-wife’s abduction, Shin was considering moving to Hollywood to continue his career. After a few days in Hong Kong, he, too, was taken to Pyongyang.

Shin was a less compliant “guest” than his former wife (whom Kim Jong-il had put up in one of his finest palaces) and made several escape

attempts. As punishment, he was sentenced to four years in prison. Once he promised to stop trying to escape, he was released. On March 6, 1983, Kim Jong-il staged a party to reunite the couple. “Well, go ahead and hug each other. Why are you just standing there?” he said. The room erupted into applause as the two embraced. The Dear Leader hushed the crowd. “Comrades. From now on, Mr. Shin is

my film adviser.” The attraction of Shin was considerable. He was the most creative and influential director in South Korea, so his “defection” would be perceived as a criticism of its system. Shin was Kim’s ideal director: trained in Japan and China, he had made films in the United States and was familiar with the most recent Western film techniques. Yet he was Korean (born in prewar

North

Korea,

no less), so Kim couldn’t be accused of bowing to the imperialist West.

Movies have played an important role in North Korea since 1948, when Kim Il-sung lured South Korean filmmakers north with promises of unlimited funding and artistic freedom. Kim believed film was the perfect medium for raising national consciousness. Dozens of duplicates of every North Korean film were circulated throughout

the country, with color copies going to the big cities and black-and-white to rural areas. Movies about Kim Il-sung himself were always distributed in color, and only on the highest-quality film stock from the United States (Kodak) or Japan (Fuji).

Before entering politics proper, Kim Jong-il ran the Movie and Arts Division of the Workers’ Party Organization and Guidance Department. Kim was a

huge film buff who watched movies every night. Enlisting the aid of North Korea’s embassies, he had thousands of foreign films shipped back to him via diplomatic pouch.

6

His favorite movies were reported to be

Friday the 13th

,

Rambo

, and

Godzilla

. Soon after releasing Shin from prison, Kim took him to his twenty-thousand-film archive, a three-story humidity- and temperature-controlled, guarded

building in central Pyongyang. The archive had 250 employees: translators, subtitle specialists, and projectionists. But no individual was more important than the director in helping the people develop into true Communists. “This historic task requires, above all, a revolutionary transformation of the practice of directing,” Kim wrote in his 1973 treatise,

On the Art of the Cinema

. Kim wanted

Shin to improve the North’s film industry so it could produce movies worthy of the international festival circuit. North Korea would press the cause of world communism by getting films into Cannes.

The combination of political and financial pressure had driven Shin’s South Korean film company out of business, and rumors were circulating that he had defected to the North voluntarily in order to

advance his career. If Shin wanted the South Korean authorities to believe he had been abducted, he needed evidence. On the evening of October 19, 1983, Choi and Shin met with Kim Jong-il in his office. Choi had purchased a small tape recorder, which she carried in her handbag. The three sat around a glass-topped table drinking. Choi pretended to reach into her bag for a tissue and quietly turned

the recorder on. She and Shin took turns asking Kim leading questions: Why did you bring us here? How did you organize our kidnappings? Clearly enjoying the repartee, Kim talked a blue streak. “I’ll confess the truth only to you two,” he said. “But I would appreciate it if you keep this a secret just between ourselves.

“Frankly speaking, we still lag behind the Western countries in motion pictures,”

Kim explained. “Our filmmakers do perfunctory work. They don’t have any new ideas. Their works use the same expression, the same old plots. All our movies are filled with crying and sobbing.” He was in a difficult situation. How could he open the country to outside influences without jeopardizing his control? He had sent directors to study in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union,

but he couldn’t allow them to go to Japan or the West. That was why Kim needed Shin so urgently. Shin said he was flattered, but wondered exactly why Kim had gone to the lengths of

kidnapping

them. “I absolutely needed you,” Kim answered. “So I began to covet you, but there was nothing I could do. So I told my comrades, if we want to get Director Shin here, we have to plan a covert operation.”

Toward the end of the conversation, Kim offered a weak apology. “I’ve also conducted my own self-criticism,” he said. “That’s because I never told my subordinates in detail what my plans were. I never told them just how we would use you and my intentions. I just said I need those two people, so bring them here. As a result, there have been a lot of mutual misunderstandings.”

7

The tape ran out after

forty-five minutes, and Choi was too frightened to change it. It didn’t matter. She and Shin had the proof they needed.

Shin continued to make films for the next three years, directing seven and producing eleven more. As Kim grew to trust the couple, they were allowed to travel more, first in the Eastern Bloc and eventually beyond, although always accompanied by minders. On March 13, 1986, they

escaped during a film festival in Vienna, evading their minders’ car and asking for asylum at the U.S. embassy.

On hearing about their escape, Kim Jong-il assumed they had been kidnapped by the United States. The possibility that artists with whom he had been so generous would abandon him was too much for Kim to imagine. He sent a message offering to help them return to Pyongyang. They never

replied.