The Iron Woman (8 page)

Authors: Ted Hughes

‘Mess,’ wailed the great face. ‘Mess.’

‘Who are you?’ thundered the Iron Woman from deep inside. ‘Say it again.’ And her pounding

dance-steps

shook the hill in time to her words, while the Cloud-Spider jerked and contorted, like a rubber

comedian’s

face.

‘I am Mess. I am Mess,’ came the sobbing wail.

‘And who will clean you up?’ came the Iron Woman’s voice, her words timed to her stamping dance-steps and the weird whanging boom that shook the hill. ‘Who will clean you up? Who? Who?’

‘Mother,’ wailed the vast snail of a mouth.

‘Who?’

‘Mother.’

‘Who?’

‘Mother.’

‘Tell us again. Who?’

‘Mother will clean me up.’

But now the Cloud-Spider was beginning to turn, as the dancing Iron Woman began to turn inside it,

dragging

it with her like a gown. Its wail grew agonized, higher, thinner. Its edges were being dragged towards that turning centre, like spaghetti being rolled up on a fork. As it turned it rose upwards, turning faster. Soon it was spinning, like an immense whirlpool. The Iron Woman’s revolving dance had turned into something else. Something that climbed into a spinning column. The cloudy body and webs of the giant spider were twisted tightly round it.

‘It’s the Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon,’ cried Hogarth. ‘Going back up. It’s taking the horrible cloud with it.’

‘But what about the Iron Woman?’ cried Lucy.

Sure enough, the long, swaying, whirling corkscrew of darkness was going up – just as they had seen the Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon coming down. Lucy and Hogarth couldn’t take their eyes off it. The Cloud-Spider was now completely wrapped around that

spinning

column in tight webby folds, with a few raggy

skirts of it flinging out here and there. Somewhere in there the eight eyes must be stretched out long and flat and thin like elastic. But where were the Iron Woman and the Iron Man?

They watched the writhing column climb into the sky, with its corkscrew tip now piercing upwards,

worming

upwards. Huge and dark and towering, it swayed as it climbed. Growing smaller, as it climbed away. Soon it was a wispy blot, high in the blue. Then a dithering dot, like a skylark. They watched it, and watched it, till at last they were staring into nothing.

They looked down the hill. The air was so clear, in the morning sun, the town seemed to be sparkling. The Iron Woman and the Iron Man were just coming out of the woods, climbing towards them. Lucy ran towards them. Then stopped. Hogarth joined her. The two giants stopped.

‘Oh!’ cried Lucy. ‘Are you all right?’ The Iron Woman was no longer a beautiful, gleaming blue-black. She was the colour of an iron fire-grate after many fires, rusty pink and grey-blue. And the Iron Man was the same. As if the inside of the Cloud-Spider had been a furnace of some kind.

‘Go home now,’ said the Iron Woman. ‘And watch. Wait and watch.’

The Iron Man said nothing, just raised his great hand.

*

Like everybody else, Lucy’s mother had heard and watched the tremendous storm of happenings in the dark cloud. And she too had watched the spinning blur climb away into nothing. As if the whole terrific

tempest

had drained into the blue sky through an upward plughole. She was still standing at the window in a daze when a voice behind her complained:

‘Towels, where are all the towels?’

She turned. There was her husband, stark naked except for a skimpy hand towel, shivering and

goose-pimpled

from head to foot, with a seven-day beard, his hair plastered down over his brow, and a woebegone expression on his face. But, worst of all, the stubbly beard and the hair, that should have been black and curly, were now snow white.

‘Charlie!’ she screamed, and fainted.

*

So it seemed to be over. All the men climbed out of the rivers, the ponds, the swimming pools, the baths. Women ran everywhere, with bags full of clothes and towels. Slowly, life started up. Lights came on. Cars began to move. Shops opened. Telephones rang

incessantly

.

But things had changed. For one thing, it was not only Lucy’s father whose hair had gone white. Every man who had been a fish, or a seal, or a water-bug, or a

leech, now had white hair. Men who had been grizzled, or nearly grey, or grey, stared into their mirrors at their silvery white hair and cried: ‘Oh God, I look like Granny!’ or else ‘But my face isn’t any older, is it?’ And young men whose hair had been curly gold or glossy auburn brown or mousy hardly dared catch sight of themselves in their car mirror, or in a shop window. ‘It’s no wonder,’ they said to their wives or girlfriends. ‘What we went through was no joke. Worse than seeing a

thousand

ghosts! You’d have gone white too.’ Within days, hairdressers and chemists were out of hair dye.

But other things had changed for the better. Everybody realized straightaway that the terrible scream no longer blasted them when they touched each other. Instead they now heard it all the time, but only faintly – like a ringing in the ears. And strangely enough, it came and went.

It was easy to see what made it come. When you looked at the waste bin, it came noticeably stronger. And when you poured soap powder into the washing machine, it seemed to zoom in on you and go past very close, like a jet going over the house – but a jet powered with those screams. It was a bit of a shock. And when Mr Wells, with his little white moustache, looked at his stacked drums of toxic waste, it came nearly full strength, a painful screech in his ears, like something coming straight at him, and he had to look away quickly.

So nobody could forget. Farmers stood in their fields, listening and thinking. Factory owners sat in their offices, listening and thinking. The Prime Minister sat with his Cabinet Ministers, listening and thinking – and whoever spoke, the others looked at the speaker’s weirdly white hair and listened more carefully, and thought more deeply.

They had all learned a frightening lesson. But what could they do about it?

They soon found out.

*

Already, next morning, an odd thing was noticed. The first men back to work at Chicago saw a yellow net, like a massive spider’s web, draped thickly over the stacks of drums full of poisonous chemicals. Each strand was the thickness of a pencil, and brittle, so it broke up into short lengths. It was a mystery.

The same webs were draped over all the waste dumps in the country. Over all the rubbish heaps. Over all the lagoons of cattle slurry. The same stuff.

Chemists were baffled by it when they tried to find out what it was. But pretty soon they found what it was good for. It was the perfect fuel. Dissolved in water, it would do everything that oil and petrol would do, yet fish could live in it. It would burn in a fireplace with a grand flame but no fumes of any kind. And that first morning there were thousands of tons of it.

Next morning, the same. And now everybody could see that the rubbish and the poisonous waste were being mysteriously changed into these yellow webs during the night.

Even if you had a little rubbish heap in your back

garden

, you would have a web on it next morning. Or a web where it had been. Then you could dissolve it in water and run your car on it for a while.

Strange!

People soon realized what was happening. At

nightfall

, a mist gathered over any rubbish, wherever it might be. A dark, webby, smoky mist. Just like the clouds of puff that had bubbled from those suffering men when they were fish and newts and frogs. And next morning there was the yellow web – and the rubbish had gone. Or most of it had. Another night and it would be all gone. As if the mist had eaten the rubbish and left a web.

No wonder they called it a miracle. It happened in no other country.

But wherever the rubbish or the waste leaked into a stream or a pond, the mist would not form. Once that leak was stopped, sure enough next night the webs would come. So everybody stopped those leaks because everybody wanted the magic fuel.

Mr Wells didn’t have to scratch his bald head for long. He blocked all those outlets into the river and simply

stacked the waste – where it soon turned into yellow webs. Then each day his men harvested the yellow webs. Now he could import waste from all over the world. The more the better. All his suppliers had to pay him to take it, of course. Then he sold the yellow webs. Soon he could triple all his wages.

And soon, too, they found it was better than manure. Or, treated this way, it would kill Colorado beetles and nothing else. Treated that way, it would keep out thistles. It could be made to do anything.

Of course, nobody knew what had really happened. ‘A miracle!’ they said, shaking their heads. ‘Truly.’

‘Our problems,’ said the Prime Minister, ‘seem to be strangely solved.’

*

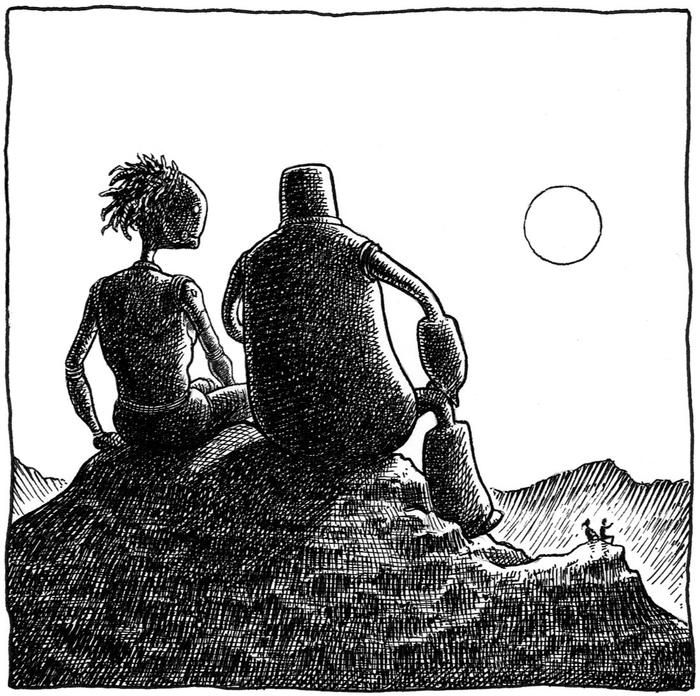

Hogarth had to go home. On that last morning, he and Lucy climbed the hill together. It was the third day of the webs. Everybody was still baffled by these strange, brittle, yellow nets. Lucy and Hogarth were no wiser than anybody else. But they knew it had to do with that terrific fight, when the Iron Woman had clawed her way down the Cloud-Spider’s throat and fought it from the inside with her dreadful dance and the star power of the Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon. Something to do with the way the Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon had whirled it into a spinning blur, and taken it upwards.

There were the Iron Woman and the Iron Man,

sitting

on the hilltop stones, among the cedars. The Iron Man had brought up the birdwatcher’s car out of the marsh. He was folding pieces of it into handy shapes. They seemed to be having a picnic together. Every trace of their scorching and burns had disappeared. In fact they seemed brighter than ever. The Iron Woman’s

blue-black

looked new-made. Lucy wondered if they had been polishing each other. She and Hogarth sat on the grass near by, gazing at them.

‘Iron Man, can I ask you something?’ said Hogarth after a while.

The Iron Man swivelled his head slightly and stopped chewing, to show he was listening.

‘Where are the yellow webs from?’ asked Hogarth.

The Iron Man started to chew again. He seemed to be looking at the Iron Woman. Minutes passed. Finally the Iron Woman spoke.

‘Where from?’ she said. And paused.

She went on chewing a while. She was bent over something in her lap, that she worked at carefully. Then her voice came again, rumbling somehow from beneath them, or echoing somehow from all around them. ‘Where,’ she asked, ‘did the Cloud-Spider come from?’

‘The bubbles!’ cried Lucy. How could she forget those bubbles.

The Iron Woman chewed. She seemed not to have heard, as she worked at whatever it was in her lap. Then

her voice came again: ‘And the bubbles? Where did they come from?’

Both Lucy and Hogarth were thinking the same thing. Obviously the bubbles had come from – well, from inside Lucy’s father, for one. When he was a giant newt. And from inside Hogarth’s father when he was a giant frog. And from inside all the other men.

Lucy frowned. Was the Iron Woman saying that the yellow webs, or whatever was making the yellow webs, was the same thing that made the bubbles? Inside her father? And inside the others? Somehow? How could that be? But the Iron Woman’s voice was rumbling again.

‘Big, deep fright,’ she said. ‘Big, deep change.’

Lucy thought about her father’s hair. That was big change, all right. But still, it was only hair. Whatever had made those bubbles – that’s where the change must be. That was deep. But what was it? And how could it …? Lucy and Hogarth were lost in their thoughts, as they gazed up at the huge, mysterious faces.

Then the Iron Woman reached out and laid over Lucy’s shoulders a heavy, cool necklace made of flowers from every month in the year. Later, when Lucy counted them, there were fifty-two different kinds of flowers. The giant hands came out again and laid another flower necklace, exactly the same, over Hogarth’s shoulders. Then she lifted both her hands and laid another flower

necklace, very much bigger, very thick and heavy, made entirely of foxgloves, round the neck of the Iron Man. Finally, she put one over her own head, and arranged it across her breast. This one, Lucy saw, was made entirely of snowdrops.

The four of them sat there, in the warm, morning sun, not saying anything. Lucy and Hogarth simply watched the huge faces of their strange friends, and

listened

to the faint sound in their ears. This sound, they now noticed, seemed to have become stronger and different. It was not the faint sound of the creatures

crying

. It was music of a kind, from far off, far up. They both looked up into the blue, gazing and listening. It was not a skylark.

Ted Hughes was born in Yorkshire in 1930. His first book,

The Hawk in the Rain

, was published by Faber in 1957, and was followed by many volumes of poetry and prose for both children and adults. He was Poet Laureate from 1984 and was appointed to the Order of Merit in 1998, the year in which he died.