The Isle of Devils (14 page)

Read The Isle of Devils Online

Authors: Craig Janacek

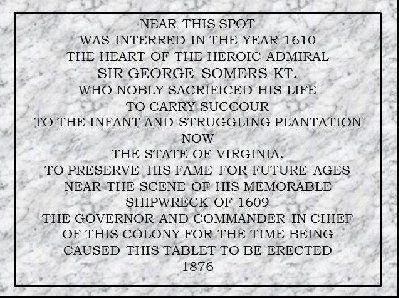

The object of my attention proved to be a plain sarcophagus, whitewashed on the sides with a featureless grey slab of stone on top. Grey painted bricks formed an archway and wall above it, and partly protected the tomb from the elements, though its stone was already weather-stained and lichen-blotched. Set into those bricks was a white

marble

slab that explained why such an object was found outside of a church or graveyard.

I must admit that I was moved by this saga of a great hero. I reverentially laid my hand upon the stone slab and silently pondered what stirrings of the soul led a man to rise to the heights of human triumphs, so that his name would never be forgotten to the annals of history.

“‘The proper study of Mankind is Man,’” a woman’s voice suddenly pierced my reverie. I turned about suddenly, only to discover the stunning woman that I had encountered only just this morning in the hotel’s entryway and whose face had never left my mind’s eye. She had put on a thin mantle and a bonnet, which protected her fair face from the full glare of the sun, but had the unfortunate effect of partially obscuring her lustrous red hair. She had also donned elbow-length white gloves, and carried a trim little hand-bag of crocodile skin and silver.

“I beg your pardon?” I finally stammered.

“Pope,” she said simply. “Alexander Pope?” she elaborated slightly, raising her eyebrows, after witnessing what I can only imagine was a completely blank look upon my face.

“Yes. I am familiar with his works,” I finally replied. “But I am at a loss as to what Pope has to do with anything?”

“You were contemplating the final resting place of Somers’ heart. Since he died over two hundred years ago, even if you happened to be directly related to Sir George, you cannot possibly have been specifically grieving his passing. Thus I assumed that you were engaged in a more profound introspection of the nature of man, and Pope seemed germane. Only by studying the exploits of the great men – and women, mind you – can we ourselves be elevated to perform a momentous deed,” she concluded, smiling broadly.

“I believe that you may have just read my mind. I stand flabbergasted.”

“It was nothing. You have a very expressive face. I am Lucy, by the way.” She held out her hand in a very manly fashion. From this action and her distinctive accent, I could only assume that she was an American, which was surprising, since her husband was clearly French.

“A pleasure to meet you, Madame Dubois,” I said and introduced myself in turn.

A wary expression entered her dazzling green eyes. “Do I know you, sir?”

I laughed. “No, I simply heard Mrs. Foster call your husband by that name as I descended the stairs this morning.”

“Ah,” the wariness disappeared, “you are very observant.”

“No more so than yourself. As you said, ‘the proper study…’” I let the sentence trail off.

“

Touché

,” she nodded her head. “So tell me, sir, do the deeds of Sir George inspire you?”

“How can they not?” I replied. “Of course, Somers is but one of many brave men upon whom the bedrock of the British Empire was laid. Even today, great men walk amongst us. Take General Gordon for example.”

“Chinese Gordon?”

I frowned. “I’m not certain that he cares for that sobriquet. It is true that he made his military reputation in China as the head of the Ever Victorious Army, a band of Chinese soldiers led by European officers, who put down the much larger forces of the Taiping Rebellion. But I think he is more to be admired for his work in the Sudan suppressing the slave trade.”

“I will grant you that,” she conceded.

“And you, Madame Dubois? You said that women were also capable of great deeds. Which woman inspires you?”

“I am partial to Boudica,” she said.

I raised my eyebrows at this statement.

“You disapprove, sir?” she said.

“Not at all,” I shook my head. “It is simply that I was not expecting such a violent example. I had simply presumed you would reference someone more gentle; Florence Nightingale, for example.”

She inclined her head. “It is a valid point.” She pursed her lips, apparently lost in thought. “We do so glorify the warriors of this world, often forgetting that bravery takes many forms, and you need not set foot on a battlefield to prove it,” she said seriously.

“They also serve who only stand and wait.”

The frown vanished from her forehead, and she smiled broadly at me. “Milton. Exactly! You know both your history and your literature, sir. Tell me, what else do you enjoy reading?”

“Recently I have appreciated the works of Collins, Poe, and Gaboriau.”

“Ah, said she, a hint of disdain in her voice. “I don’t take much stock of them. They were smartly written, I suppose, and have some small talent, I grant you, but nothing worthy of significant attention. Perhaps someday an author will emerge who will shake the very foundation of modern fiction, but I have yet to read him.” She paused and stared intently into my eyes. Then she seemed to make a decision. “Will you walk with me, sir?” she said, as she offered me her arm.

I suddenly realized the precariousness of my position. “Ah, Madame Dubois, I am not certain that…”

She laughed at my obvious discomfort. “Do not fear, sir. I won’t bite. And please call me Lucy.”

“I assure you, Madame Dubois, that I am not worried about myself. Your husband…” I trailed off, the implications clear.

She smiled. “Hector? Do not worry about Hector. I promise you that he will not be the slightest bit concerned if I spend a few moments with a respectable gentleman in a highly public

locale.” She looked down on her outstretched arm. “You are a gentleman, are you not? Would you forsake me?”

I drew in a deep breath as I realized that I had little choice. I took her arm, careful to not make any more contact with her slender body than absolutely necessary. As I did so, I absently noted a small black ink stain on the inner aspect of her right glove. Once she had secured my arm, she led me back along one of the gravel paths towards the larger part of the garden. At her touch, it seemed as if all of her senses were heightened. The sun was shining very brightly, and yet there was an exhilarating crispness in the air, which set an edge to a man's energy.

“Tell me about yourself, sir,” said Madame Dubois, as we sauntered through the garden.

“It’s a simple story, really,” I said awkwardly, not overly comfortable discussing my life with someone I had just met, no matter how entrancing she may be. “I was born twenty-eight years ago in Edinburgh, Scotland. But I have few memories of my ancestral home, as my father moved our family to the Australia Colonies when I was less than a year of age, and my brother Henry but a boy of three.”

“Why?” she inquired softly.

“You are likely too young to recall what happened in Australia in 1851. John Dunlop discovered gold there, and by November a cataract of that precious metal was pouring from the hills. Wherever gold is found, you will soon find a swarm of men seeking their fortune, and my father was no different. Within a few months, more than fifty thousand people, gathered from every nation on the globe, were on the diggings.”

“I know a little of this phenomenon, Doctor,” smiled the lady, faintly. “My father was about to become a young man in Philadelphia, when gold was found at Sutter’s Mill. Within a few years, like so many others, he rushed to California. There he met my mother, and eventually I was born in San Francisco.”

“Ah, it is amazing that a little metal can so greatly shape the course of our lives.”

“Indeed,” she agreed. “But I interrupted your tale. Please continue.”

“Well, I am told that we traveled on a boat of the Adelaide-Southampton line, but my dear mother did not survive the voyage. My father was not an overly-affectionate man, so my brother Henry and I raised each other. Whether my father was too late, too unlucky, or too scrupulous, he

failed to acquire any significant fortune. There was no ‘Welcome Nugget’ for him. But he was modestly prosperous, and once my brother was thirteen, my father realized that the two of us were becoming rather wild in the freer, less conventional atmosphere of South Australia. He determined that we lads could not obtain a sufficient education in the colonies, so Henry was sent back to England to board at Winchester College at the old English capital, while I followed two years later. I will never forget how he put his hand on my shoulder as we parted; giving me his blessing before I went out into what he knew to be a cold, cruel world. It was the last time I would ever see him. I had always meant to make the passage back, but it always seemed like something arose that made it impossible, such as my medical training. And now, of course, I have little reason to go back to Australia.”

“That is a sad story, Doctor. Do you have no fond memories of your childhood?”

I contemplated this question for a moment. “My school days were mighty fine. I spent my days learning everything I could, and my nights making every mischief we could devise. Those were good years for old number thirty-one.” I smiled fondly at the reminiscence.

“Thirty-one?”

“My school number, used by the tutors to identify me amongst the other boys.”

“Ah, I thought perhaps those were the number of hearts you broke. Surely not all of your time was spent in boy-hood pranks? There must have been more than a few girls who fell for your handsome visage?”

“Ah,” stammered I, staring at her in stupid surprise. “I…. do not know what you mean.” I was completely at a loss of how to respond to her provocative words.

But she merely laughed gaily. “So why did you become a doctor?” she asked lightly.

I reflected upon this most personal question. In many circumstances, such a probe would have been considered rude, but I knew that Americans were frequently not as constrained by social circumstances as those of us who consider England home. “I suppose it was the loss of my mother. I had a great anger that I had no clear memories of her, and I vowed to try my best to prevent such a loss for others.”

Now it was Lucy’s turn to grow serious. “And do you think that anyone can really affect the fates in such a fashion, Doctor?”

“Perhaps not, perhaps it is hubris. But such were my thoughts when I left Winchester in order to attend the University of London. During that time, I served as a surgeon at St. Bart’s Hospital. With my dresser Stamford, we dealt with many gruesome wounds…”

“Dresser?” Lucy interrupted me to inquire.

“Ah, a term we use for a surgeon’s assistant,” I explained.

“Of course, please continue.”

“Well, after I obtained my M.D. I realized that it was not easy for a man without kith and kin to set up practice for himself. And so I decided to follow in my brother’s footsteps by joining the Army. I did a residency at the Royal Military Hospital at

Netley

, near Southampton, where I saw men arriving on the incoming hospital ships from all parts of the Empire. And then I myself was shipped out to India. Upon landing in Bombay, I was attached to the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers as an Assistant Surgeon and saw service in India and eventually Afghanistan. I was eventually transferred to the Berkshires Regiment, where I encountered some action around

Candahar

.”