The Italian Boy (3 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

The Watch House, Covent Garden, circa 1830; St. Paul’s Church is to the right in the picture, the Unicorn tavern to the left, and an Italian boy can be seen just to the right of the arch.

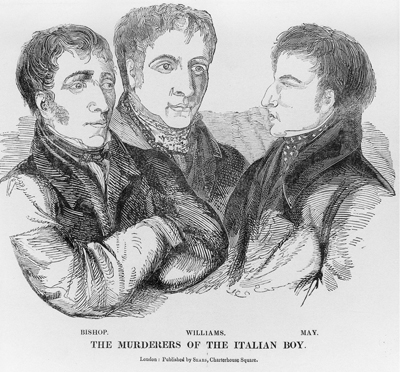

It was only at this awkward point for Corder that the prisoners were summoned from their underground cells in the St. Paul’s, Covent Garden watch house (the building was at that time being used as a temporary jail/police office; it was originally built as a place of surveillance, from which the graveyard could be guarded against snatchers and other trespassers) to give their account of how they had come into possession of the boy’s body. They entered the crowded room at the Unicorn to be viewed by a fascinated public; the memory of the crimes committed by William Burke and William Hare in Edinburgh just three years earlier was fresh. Had similar events been occurring in the English capital? And what would these monsters look like? The answer: very ordinary indeed, your common or garden Londoner. John Bishop was thirty-three, stocky, slightly sullen-looking, but with a mild enough expression; he had a long, slender, pointed nose, high cheekbones, large, slightly protruding gray-green eyes, and thick, dark hair that continued down into bushy muttonchop sideburns that covered a good deal of his cheeks. James May, thirty, was tall and handsome, with a mop of unruly fair hair and dark, glittering eyes; he looked pleasant enough. Like Bishop, he was still wearing his smock frock—the typical garment of a rural laborer—in which he had been arrested, which perhaps made him seem even more guileless; his left hand was bandaged. Thomas Williams, in his late twenties, was shorter than the other two, with deep-set hazel eyes and narrow lips that gave him a slightly cunning appearance, but mischievous rather than malevolent; his hair was mousy, his face pale, and he could have passed for someone much younger. Michael Shields just looked like a frightened old man.

The accounts of Bishop, May, and Williams of the events of Friday, 4 November, and Saturday, 5 November, given at the coroner’s inquest and at hearings yet to come, differed remarkably little from those offered by the various eyewitnesses also called to testify. There were a few discrepancies, but these would appear small and insignificant. The following train of events, at least, was not in dispute.

* * *

John Bishop and Thomas Williams

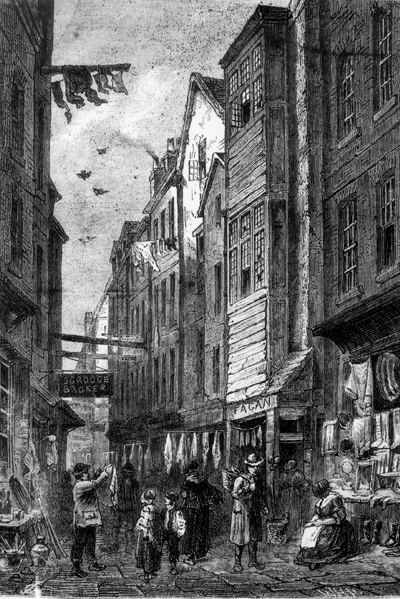

awoke in No. 3 Nova Scotia Gardens, the cottage they shared in Bethnal Green, at about ten o’clock on Friday morning, breakfasted with their wives and the Bishops’ three children, and set off for the Fortune of War pub in Giltspur Street, Smithfield—opposite St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, and a regular meeting place for London’s resurrection men. Here, they began their day’s drinking and met up with James May. May had known Bishop for four or five years and was introduced to Williams, whom May knew only by sight, having seen him in the various pubs around the Old Bailey and Smithfield. The three men drank rum together and ate some lunch. May admired a smock frock that Bishop was wearing and asked him where he could buy a similar one. Bishop took May a few streets away, to Field Lane, one of the districts given over to London’s secondhand clothes trade. Field Lane was also known colloquially as Food and Raiment Alley, Thieving Lane, and Sheeps’ Head Alley, and Charles Dickens was to add to its notoriety six years later by siting one of Fagin’s dens there, in

Oliver Twist

. A steep, narrow passage, Field Lane comprised Jacobean, Stuart, and early Georgian tenements that were largely forbidding, rotting hovels; those on its east side backed on the Fleet River—often called the Fleet Ditch, since it was by 1831 almost motionless with solidifying filth, though when it flooded, its level could rise by six or seven feet, deluging the surrounding area with its detritus. By weird contrast, the windows in Field Lane were a dazzling display of brightly colored silk handkerchiefs (“wipes”); if the commentators of the day are to be believed, the vast majority of these were stolen by gangs of young—often extremely young—“snotter-haulers,” who would soon be incarnated in the popular imagination as the Artful Dodger (though Dickens used the more polite slang term, “fogle-hunters”). Here, in Field Lane, James May bought a smock frock from a clothes dealer, then decided he wanted a pair of trousers, too, and turned the corner into West Street, where he attempted to bargain with the female owner of another castoffs shop.

3

Already pretty drunk, May was unable to agree on a price with the woman but, feeling guilty at having wasted her time, insisted on buying her some rum, which the three enjoyed together in the shop. May and Bishop then went back to the Fortune of War to have more drink with Williams, before Bishop and Williams set off for the West End, to try to sell the corpse of an adolescent boy lying trussed up in a trunk in the washhouse of 3 Nova Scotia Gardens.

Their first call was made at Edward Tuson’s private medical school in Little Windmill Street, off Tottenham Court Road, where Tuson said he had waited so long for Bishop to come up with a “Thing” that he had bought one from another resurrection gang the day before. So they walked a few streets south to Joseph Carpue’s school on Dean Street in Soho. Carpue spoke to the pair in his lecture theater with several students present who wanted to know how fresh the Thing was. Carpue offered to pay eight guineas and Bishop agreed to this price, promising to deliver the boy the next morning at ten o’clock.

John Bishop, James May, and Thomas Williams as they appeared to two court sketch artists. While Bishop’s appearance changes comparatively little from sketch to sketch, depictions of May and Williams vary dramatically and in fact the sketch above has mislabeled May and Williams in its caption.

Field Lane, one of the districts of London where secondhand clothing was bought and sold

Bishop and Williams got back to the Fortune of War at a quarter to four and shared some more drink there with May. Bishop now began to wonder whether he could get more than the eight guineas Carpue had offered—the boy was extremely fresh, after all. Bishop called May out onto the street to ask him—away from the ears of other resurrectionists—what sort of money he was achieving for Things. May told Bishop that he had sold two corpses at Guy’s Hospital for ten guineas each just the day before and that he would never accept as little as eight guineas for a young, healthy male. Bishop told May that if he were able to help sell the body for a higher price, May could keep anything they earned over nine guineas. They went back into the Fortune of War for a round to seal the bargain and then, leaving Williams drinking, set off to procure a coach and driver in order to collect the body.

This was not easy. At around a quarter past five, as dusk was falling, they approached hackney-coach-driver Henry Mann in New Bridge Street, but Mann refused to take them because, as he later said, “I knew what May was”; he hadn’t spotted Bishop, who was standing behind his cab in the increasing gloom.

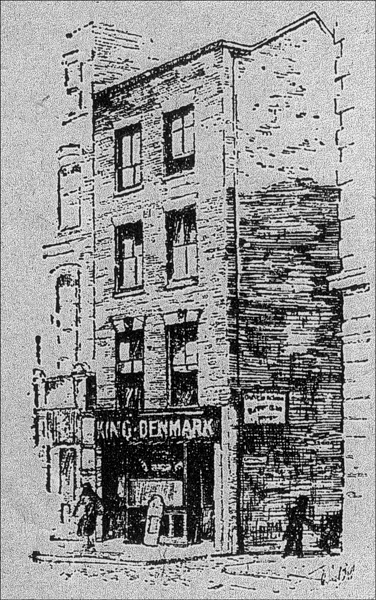

They next tried James Seagrave, who, having given his horse a nose bag of corn, was taking tea in the King of Denmark, just south of the Fortune of War. Bishop and May asked Thomas Tavernor, who helped out at the nearby cabstand, to call Seagrave out to the street. Seagrave came out, and May, leaning against the wheel of a nearby cart, asked if he would be willing to do a job for them. Seagrave, suspicious, replied that there were a great many jobs, long ones and short ones—what kind did they mean? May said it was to be “a long job” carrying “a stiff ’un,” for which trip they would “stand” one guinea. The driver was intrigued and allowed May to buy him tea in the King of Denmark to discuss the journey but also to find out more about the resurrection world. Seagrave had no intention of letting them hire him, intending to “do them,” as he later told the coroner’s court.

The King of Denmark combined the operations of inn, teahouse for cab and coach drivers, and booking office for errand carts. (It was also the best spot in London for watching public hangings, since it stood immediately opposite Newgate’s Debtors Door, where the scaffold was erected on execution days.) Inside, closely observed by a barman, May, Bishop, and Seagrave sat down to talk. During their discussion, May poured gin into Bishop’s tea from a pint bottle and Bishop protested, laughing, “Do you mean to hocus or burke me?” Seagrave did not know what this meant.

4

A man sitting close by nudged Seagrave and muttered to him that Bishop and May were well-known snatchers. His curiosity about them satisfied, Seagrave went out into the street while Bishop and May’s attention was distracted and drove off. “It won’t do,” he muttered to Tavernor on his way out. “They want me to carry a stiff ’un.” As he pulled away, he looked back and spotted Bishop and May walking up and down the Old Bailey cab rank, trying to hire a driver. No one would take them.

The King of Denmark pub in the Old Bailey, opposite Newgate’s Debtors Door

They had better luck in nearby Farringdon Street, where they found someone willing to drive them to Bethnal Green and then south of the river to the Borough for ten shillings—more than double the going rate for such a journey. But there was yet more drinking to fit in first, and Bishop and May took the driver to the George pub in the Old Bailey (where Williams had arranged to meet them) and then on to the Fortune of War for another round, before the trip to Nova Scotia Gardens.

They arrived at the Gardens at around half past six, observed by several neighbors: the doors of their hired vehicle were bright yellow, and it was a “chariot”—a grander version of the hackney coach. Bishop and May jumped out and went up the path that led to No. 3, leaving Williams chatting with the driver; the chariot door was left wide open. They were watched by George Gissing, the twelve-year-old son of the owner of the Birdcage pub, which stood opposite the Gardens (and still does). Gissing, from the doorway of the Birdcage, had a good view of the men. He recognized both Bishop and Williams, though not May; he saw that Bishop and May were in smock frocks and that May was smoking a pipe. Another youth, Thomas Trader, observed the three men too, recognizing Bishop and Williams, as did a local girl, Ann Cannell. Cannell’s mother passed by and started to watch as well, saying to Trader, “This looks strange. See where they are going so quick.” But Trader replied, “I’m sure I won’t go after them. If I did, they wouldn’t mind giving me a topper” (boxing slang for a violent punch).

5

But the boy did try to note the license number of the chariot, though it was obscured by the open door and he gave up when he saw the driver staring at him. After ten minutes or so, Williams went down the path to the cottage and shortly afterward returned with Bishop and May. May was carrying a sack and Bishop was helping to hold it up. They placed it in the chariot, all three men got in, and they drove off.