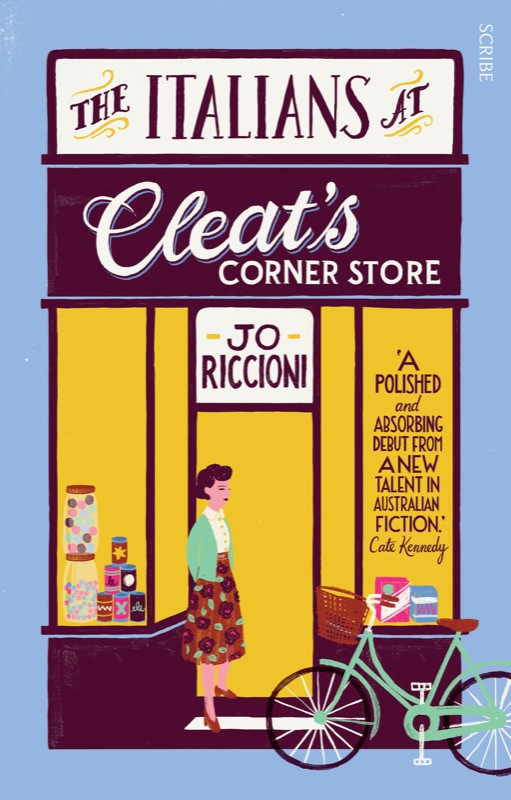

The Italians at Cleat's Corner Store

Scribe Publications

THE ITALIANS AT CLEAT'S CORNER STORE

Jo Riccioni was born in the UK to an Italian father and English mother. She worked in Singapore and Paris before settling in Sydney, and she has a master's degree in literature from Leeds University. Her short stories have been read on the BBC and Radio National, and published in

The Best Australian Stories

2010 and 2011. Her story âCan't Take the Country out of the Boy' has been optioned for a short film.

Scribe Publications Pty Ltd

18â20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

50A Kingsway Place, Sans Walk, London, EC1R 0LU, United Kingdom

First published by Scribe 2014

Copyright © Jo Riccioni 2014

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The epigraph by T.S. Eliot is reproduced with the permission of Faber and Faber. The quotation in the first chapter is from âItalia, Italia, o tu cui feo la sorte' by Vincenzo da Filicaja. The quotation in the fifth chapter is from

A Room with a View

by E.M. Forster, reproduced with the permission of The Provost and Scholars of King's College, Cambridge, and The Society of Authors as the E.M. Forster Estate. The quotation in the sixth chapter of part two is from âSea-Fever' by John Masefield, reproduced with the permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of John Masefield.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Riccioni, Jo, author.

The Italians at Cleat's Corner Store / Jo Riccioni.

9781922070883 (Australian edition)

9781922247391 (UK edition)

9781925113020 (e-book)

1. Immigrant familiesâGreat BritainâFiction. 2. ItaliansâGreat BritainâFiction.

A823.4

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

In memory of my mum,

Pat Riccioni (nee Waiton)

1940â2007

Dimmi chi sono, non mi dir chi ero

(Tell me who I am, not who I was)

Italian proverb

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter's afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

T.S. Eliot,

Little Gidding

Leyton

1949

The first time she saw them, they were mending the gate on Henry Repton's land. She was cycling to Leyton on her way to Cleat's and had reached the top of the hill that was good for sitting upright and freewheeling. She might have missed them, coasting at speed as she was, the hedgerow budding thickly on either side of the lane, but as she rounded the corner at the dip, there they were, two of them, their heads bent together over the broken gate, tools in their hands. One had his face obscured by a shock of hair, slick and jet as a raven's wing. They both stood up as she flew by, and she couldn't help but glance back over her shoulder to see the shine of their brown faces and forearms in the clean light of early morning, their neat, compact waists as they straightened. One of them put his fingers to his mouth and let out a high-pitched whistle.

As she pedalled towards Leyton, she could no longer see them, but their voices hung in the air, foreign words rolling over one another, rapid and restless and no more meaningful to her than the chatter of pebbles in the brook after a downpour. Afterwards she heard a laugh â she guessed it was the whistler â loud and playful, cutting the morning in two, and then she heard no more.

âEye-ties,' Mrs Livesey fired across the counter, as Connie raised the blind and flipped the

Open

sign in the window of Cleat's. The string bag on Mrs Livesey's arm danced under the trembling shelf of her breasts. Connie finished buttoning her serving coat and said nothing. Mrs Cleat was resting her flour scoop on the countertop, fixing her customer with small, hard eyes, like a hedgerow animal disturbed. After a moment, she motioned Connie towards the sacred domain of the new Berkel compression scales, presenting her the scoop with both hands, like a sceptre. It had been Connie who had talked Mrs Cleat through the instruction booklet and the complexities of the weighing grid when the scales had first arrived, but this was a detail Mrs Cleat chose to forget, except in times of urgent distraction. She rounded on Mrs Livesey.

âEye-talians?' she demanded, perhaps more greedily than she'd intended.

âEye-ties, that's what I said. Back again. For farm work. Paid this time.'

âI see,' said Mrs Cleat. She cast her eye past Mrs Livesey as if down an imaginary queue of customers at the counter. Connie could tell she was peeved that a farmhand's wife, and a shabby one at that, had the advantage of such news. Mrs Cleat prided herself on being the most informed woman in the Leyton and Parishes Christian Ladies' League, not to mention the Greater Huntingdon Amateur Operatic Society. She was the one to whom others came precisely because she did

not

gossip. Mrs Cleat gave

updates

. It was true that most of the village placed her version of news not far below the hallowed authority of the BBC. But Connie knew, from being in the shop with Mrs Cleat five days a week, that these

updates

had to come from somewhere, and that somewhere was largely countertop gossip.

âI see,' Mrs Cleat said again, buffing the new Formica with a cloth.

âApparently, Henry Repton told one of his WOPs there'd always be work for him on the farm if ever he wanted it. Well, that's done it. Eye-tie's come back and brung the whole ruddy family. Get that.'

Even from behind, Connie saw the change in the set of Mrs Cleat's shoulders, the marginal shift of her hips. She would not be told, least of all told what to

get

.

âYou do read the newspapers, don't you, Janet?' she said in her Christian Ladies voice. Connie smiled: Mrs Cleat knew very well that the only newspaper they'd ever sold Mrs Livesey was a royal-wedding edition two years ago. âThey say there's no jobs on the Continent. And anyone who's got one is wheeling their wages home in a barrow.' She proceeded to ply Mrs Livesey with the paper packages Connie had placed on the counter and topped them with an air of worldly superiority.

Mrs Cleat enjoyed regurgitating the casual items of global news that Mr Gilbert shared with them when he picked up his morning

Times

on the way to the schoolhouse. No doubt she felt that this snippet, opportunely recalled, redeemed her somewhat in the face of Mrs Livesey's scoop.

âThat's all well and good, but what about our boys?' Mrs Livesey continued. âIt's their jobs these WOPs are taking.' She re-adjusted the loaded bag on her arm, her cleavage rising ominously.

âWith respect,' Mrs Cleat said, the words again stolen from Mr Gilbert, who often used them as a gentle precursor to correcting the ill-informed, such as Mrs Cleat herself, âI hardly think your Derek will want a job mucking out pigs on Repton's farm. And even if he did, he wouldn't do it for twice the money Repton'll be paying them Eye-talians.'

Mrs Livesey pulled her chin to her neck. âWell, Eleanor,' she said, âI knew you liked your opera singing and whatnot, but I didn't think you were such a â¦' She scanned the shelves, searching for the answer as if it might be hidden among the tins of Vim and boxes of Rinso. âWell, such a ⦠a bloody WOP-lover, that's what,' she finally gave in. âIn the book, if you please.'

Mrs Livesey began to heave herself about when the sight of Connie, who was opening the ledger, evidently put her in mind of a more sophisticated line of attack. âHow's your Aunty Bea, dear? Still grafting away at the Big House?' she asked. Her tone suggested Connie's aunt was a manacled slave of the Reptons' rather than their paid housekeeper. âI'm sure Bea Farrington's memory isn't as short as some people's hereabouts.'

Mrs Livesey's nostrils still glistened from the early walk across the fields, and the tip of a rogue canine tooth pressed onto her lower lip even when her mouth was closed. Connie was reminded of the hounds at the Hamerton Hunt: harmless creatures in the yard, but killers on the scent. âI'm not sure what you mean, Mrs Livesey,' she replied, although she suspected she did.

âPoor Bea. Working alongside prisoners in the war is one thing, but having them back in peacetime to rub salt in your wounds is another. I'm surprised your Uncle Jack still lets her work up at the Big House, seeing as how them Eye-ties was the death of his own brother.' She glanced at Mrs Cleat, smugly gauging her response to this rather clever equation. âMonte Cassino, wasn't it, where Bill Farrington fell?'

Connie closed the ledger and returned it to its shelf under the counter.

âI don't know ⦠that is, my aunt and uncle don't really speak of it,' she said. âAnyway, she wouldn't see the Italians much â farmhands don't have any call to go inside Leyton House.'

âGive her my sympathies,' Mrs Livesey said, as if Connie hadn't spoken a word. She gave a last triumphant sniff in Mrs Cleat's direction before she headed for the door, the squeak of her rubber boots and the tinkle of the bell sounding oddly discordant behind her.

Mrs Cleat, agitated, took up the broom and began to sweep the dried mud left in Mrs Livesey's wake. âWOP-lover â¦

WOP

-

lover

?' she argued with herself. âEven if I was, which I'm not, she could have at least used the proper word. Connie â what's that

word

Mr Gilbert uses?'

Connie shook her head. She knew exactly the term Mr Gilbert sometimes used about himself, but she also understood the repercussions of educating Mrs Cleat.

âAh, that's it,' Mrs Cleat said, propping up the broom and appearing fortified by the efficacy of her own memory. âWOP-lover, indeed! Still, you can't expect the likes of Janet Livesey to know a word like

Eyetaliphile

.'

Connie began to look out for them on her way to and from work, squeezing her brakes and forfeiting the thrill of coasting round the bend at the entrance to Repton's in the hope that she might catch sight of the Italians. But a week passed and the single sign of their existence was the thin line of smoke from the chimney of the crumbling gamekeeper's cottage. She took to stopping in the greying light after work, dismounting and pushing her bike up the hill towards Bythorn. After the strictures of Mrs Cleat's shop, she usually enjoyed the challenge of pedalling up the rise, the perverse sense of release she felt from the pounding of her heart, the sweat breaking over her skin. But the walk allowed her more time to survey the squat, derelict building across the fields; to conjure them from the dusk, somehow bright and radiant, the light of a foreign sun in their hair, the sheen of it in their skin.