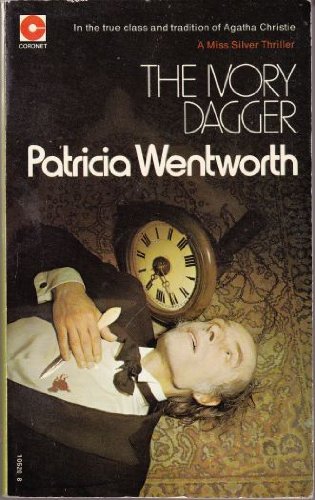

The Ivory Dagger

The young man in the hospital bed threw out an arm and turned over. His first conscious thought was that he must have called out, because the sound of his own voice was ringing in his ears, but he didn’t know why he had called out or what he had said. He blinked at the light and got up on his elbow. There was a screen round his bed. The light came in over the screen. He blinked at it, and a nurse came round the edge of the screen and looked at him. She had a good plain face and nice eyes. She said ‘Oh!’ and then, ‘So you’ve waked up.’

He said, ‘Where have I got to?’

She came right up to him and took hold of his wrist.

‘Now don’t you worry. The doctor will be along to see you in a minute.’

‘What do I want a doctor for? I’m all right.’

She said, ‘That’s fine. You were in a train smash. You just had a bump on the head.’

He said, ‘Oh—’ and then, ‘It feels all right.’

She went away after that, and presently she came back again with some sort of milky cereal that tasted like baby food.

By the time this happened he had made sure that he was all there and in one piece. Actually when she came round the screen he was out of bed seeing if he could stand on one leg. The leg felt shaky, so he wasn’t too sorry to get back and take his scolding. It was part of a nurse’s job to scold when you broke the rules.

She went away when he had finished the cereal, and he lay there wondering how long he had been in hospital. He had lost muscle, and his hands were a horrid sickly white. You don’t lose a good strong tan in a day or two. He wondered just how much time he had lost, and how he had come to be in a train smash, and where he was now. The last thing he remembered was going to see Jackson in San Francisco. After that, ‘nix’, as they said over here.

It was about twenty minutes before the doctor came—youngish, darkish, efficient. He led off just like the nurse.

‘So you’ve waked up?’

This time he was ready to come back with a question of his own.

‘How long have I been out?’

‘Quite a while.’

‘How long?’

‘A month.’

‘Nonsense!’

‘Have it your own way.’

He took a long breath and said,

‘A month—’

The doctor nodded.

‘Quite an interesting case.’

‘Do you mean to say I’ve been asleep for a month?’

‘Well, no, not asleep—though you managed to put in a good bit of that, too. Just no sense—didn’t know who you were. Do you know now?’

‘Of course. I’m Bill Waring. I came over about patents for my firm. Rumbolds, London. Electrical apparatus—all that son of thing.’

The doctor nodded.

‘Well, you came in here as Gus G. Strohberger and it took us the best part of ten days to find out you weren’t. We had to wait for the Strohberger family to get back from a trip and identify you, and when they said you weren’t Gus we had to start all over again.

Bill stared.

‘What happened to my papers?’

‘The train caught fire. You’re lucky to be here, you know. Gus didn’t make it, but a grip with his name on it was only partly burned, and the guys who dug you out seemed to think it belonged to you. They got you just before the fire did. I’ll say you’re lucky.’

Bill Waring grinned.

‘Born to be hanged,’ he said cheerfully.

They didn’t let him have his mail till next day. There was a very decent letter from old Rumbold dated ten days back. Very sorry to hear about the accident. Hoped he was making a good recovery. A pat on the back for having fixed everything up before he let a train smash get him. And he wasn’t to hurry back till he was perfectly fit. There were other letters, but they didn’t matter.

There was only one from Lila. Not air mail, and dated six weeks ago. It must have been waiting for him in New York when the train went to glory. He read it three times with a frowning intensity which would certainly have made Nurse Anderson adjure him to relax. She wasn’t there, so he read the letter for the fourth time and continued to frown. There wasn’t really anything very much to frown over. The letter wasn’t very long or very informative. Lila Dryden was twenty-two. It might have been written by someone a good deal younger than that.

He read it a fifth time.

Dear Bill,

We have been very busy. It has been rather hot, and it would have been nicer in the country. I get tired in London. We dined with Sir Herbert Whitall and went to the theatre. His home has some wonderful things in it. He collects ivories, but I think most of them are rather ugly. There is a figure which he says is like me, but I hope it isn’t. He is a friend of Aunt Sybil’s and quite old. We are lunching with him tomorrow and going down to his place for the week-end. Aunt Sybil says it is a show place. She seems very fond of him, but I hope she isn’t going to marry him, because I don’t really like him very much. I thought I could go and stay the week-end with Ray Fortescue whilst she did the week-end, but she says I must come too, and it isn’t ever any good saying you won’t if Aunt Sybil wants you to. She is calling me, so I must go.

Lila

He folded the letter up and put it away in its envelope.

It was a very foolish affair,’ said Lady Dryden. ‘Cake, Corinna?’

Mrs. Longley looked, and fell. She said, ‘I oughtn’t to,’ and helped herself to the larger of the two slices already cut from the dark rich cake.

Lady Dryden acquiesced grimly. They had been at school together, and in any case she never minced her words.

‘You are putting on.’

‘Oh, Sybil!’

‘Definitely,’ said Lady Dryden. ‘Cake at tea is absolutely fatal.’

‘Oh, well—’

‘Of course, if you don’t mind—’

Corinna Longley wanted to change the subject. She had been one of those slim, rather colourless fair girls with a lot of hair, wide sky-blue eyes, and pretty little hands and feet. At fifty the hands and feet were as small as ever. The hair now hovered between a mousy brown and grey, and the slim figure had spread. She minded, but not enough to do without cake at tea. It was all very well for Sybil, who would never put on an ounce or allow anything else to happen which was not exactly planned and provided for. She had always known just what she wanted and she had always managed to get it. And the thing of all others which she had wanted and managed to get was her own way. It wasn’t just luck. Some people got what they wanted, and Sybil Dryden was one of them. Look at the way she had managed this business of Lila’s. She came back to it partly to get away from the subject of cake, and partly because it was going to be one of the marriages of the autumn and it would be nice to be in the know.

‘You were telling me about Lila,’ she said. ‘Of course she is a very lucky girl. He is quite enormously rich, isn’t he?’

Lady Dryden looked down her handsome nose and said in a repressive voice,

‘Really, Corinna!’ Then, after a slight pause, ‘Herbert Whitall is a man whom any girl might be proud to marry. He has money of course. Lila is not at all suited to be a poor man’s wife. She is not very robust, you know, and a girl has a hard time now if she marries a professional man—all the work of the house to do, all the care of the children, and practically no help to be got. I agree that Lila is extremely lucky.’

Mrs. Longley helped herself to the second piece of cake. She always did feel hungry at tea-time, and perhaps Sybil wouldn’t notice.

The hope was vain. Lady Dryden’s eyebrows rose. The pale, formidable eyes glanced at her with a momentary contempt. Very curious eyes, neither blue nor grey, but oddly bright between very dark lashes. People used to say she darkened them artificially, but it wasn’t true. Sybil’s eyes had always been just like that, pale and rather frightening, and the lashes really almost black. Corinna Longley said in a hurry,

‘I expect you are right. My poor Anne has a dreadful time— three babies, and a doctor’s house, which means meals at all sorts of hours, and not even daily help as often as not. I can’t think how she does it. I’m sure I couldn’t. But she takes after her father—so practical. Now Lila isn’t practical, is she? But I did like Bill Waring.’

Lady Dryden repeated a previous remark.

‘A very stupid affair. More tea, Corinna?’

‘Oh, thank you. Is he still in America?’

‘I imagine so.’

‘Did he—did he—how did he take it?’

Lady Dryden set down the teapot.

‘My dear Corinna, you really mustn’t talk as if Lila had thrown him over. The whole stupid affair just faded out.’

Mrs. Longley took her cup, and said, ‘Oh, no, thank you’ to sugar, in the hope that this would be accounted to her for righteousness. Buoyed up with a feeling of virtue, she ventured to say,

‘It faded out?’

Lady Dryden nodded.

‘A few months’ separation gives young people a chance of finding out whether they really care for each other. Very few of these boy-and-girl affairs stand the test.’

Mrs. Longley reflected that an engagement between a girl of twenty-two and a man of twenty-eight hardly came into this category, but she knew better than to say so. She made one of those murmuring sounds which encouraged the person who is talking to proceed, and was duly rewarded.

Lady Dryden went on.

‘I don’t mind telling you that I said a word to Edward Rumbold—he’s the head of young Waring’s firm and a very old friend. So when he told me they were sending someone out to America—something to do with patents—I said, “What about giving Bill Waring the chance?” I don’t know if it made any difference. I believe there was someone else they were going to send, but he was ill. Anyhow Bill went, and the whole thing just faded out.’

‘You mean he didn’t write?’

Lady Dryden gave a short laugh.

‘Oh, reams by every post at first. Too unrestrained. And then —well, just nothing at all.’

Mrs. Longley’s eyes widened to their fullest extent.

‘Sybil—you didn’t!’

Lady Dryden laughed again.

‘My dear Corinna! You’ve been reading Victorian novels— Hearts Divided, or The Intercepted Letters. Nothing so sensational, I’m afraid. Americans are very hospitable. Bill Waring found himself in a rush of business by day and amusement by night. He was very well entertained, and he didn’t find or make time to write to Lila. She didn’t like being left flat, and Herbert Whitall made the running. That’s the whole story, and no melodrama about it. She is a very lucky girl, and they are being married next week. You got your card?’

‘Oh, yes—I’m looking forward to it. I expect her dress is lovely. He has given her pearls, hasn’t he?’

‘Yes. Fortunately they suit her.’

Mrs. Longley leaned forward to put down her cup. She began to collect a bag, gloves, a handkerchief, talking as she did so.

‘Well, I must go. Allan likes me to be in when he comes home. Of course pearls are lovely, but my mother wouldn’t let me wear the little string Aunt Mabel left me—not on my wedding day. She said pearls were tears, and she took them away and locked them up. And of course I’ve been very happy, though I don’t suppose it had anything to do with the pearls.’

At this point she dropped her bag. It opened, her purse fell out, and a compact rolled. When she had retrieved it from under the tea-table she felt suddenly brave enough to say,

‘He is a lot older than she is, isn’t he?’

Lady Dryden said coldly,

‘Herbert Whitall is forty-seven. Lila is an extremely lucky girl.’

Afterwards Corinna Longley was surprised at her own courage. She told Allan all about it when she got home.

‘I just felt I must say something. Of course he’s got all that money, and she’ll have some lovely house, and a proper staff of servants, and everything like that. But he is a lot older, and I don’t like his face, and she was in love with Bill Waring.’

At the time, she fixed swimming blue eyes on Lady Dryden’s face and said with a choke in her voice, ‘Is she happy, Sybil?’

Lila Dryden stood looking at herself in the glass which not only gave back the slim perfection of her figure but repeated it in the great wall-mirror behind her. She could see how beautifully her wedding-dress was cut. She had wanted something softer and whiter, but that was when she was planning to marry Bill Waring. She didn’t really like the deep, heavy satin which Aunt Sybil had chosen. It reminded her of the ivory figure in Herbert Whitall’s collection. He had brought it out and set it on the mantelpiece for everyone to see and said that it was like her. She hated it. It was very old. She hated being told that she was like something which was thousands of years old. It made her feel as if—no, she didn’t know what it made her feel, but she didn’t like it.

She looked into the mirror and saw her own slim ivory figure repeated endlessly. She didn’t like that either. It was like a rather horrid dream. Hundreds of Lila Drydens going away down an endless shadowy vista—hundreds of them, all with her pale gold hair and the ivory satin dress which Aunt Sybil had chosen.

The ivory figure had once had golden hair. The gold had worn away because the figure was so very old, but Herbert Whitall had held it under the light for her to see how the gilding still clung to it here and there. She heard him say in the voice which frightened her most, ‘Gold and ivory—like you, my beautiful Lila.’

These thoughts didn’t take any time. They were there, just as the carpet was there under her feet. The carpet was there, and the floor was solid under it. It was silly to feel as if she was floating away to join all those gold and ivory Lilas in that queer looking-glass world. She heard Sybil Dryden say,

‘Do you think it would bear to come in the least possible shade at the waist?’ And Madame Mirabelle’s instant and emotional reaction, ‘Oh but non, non, non, non, non! It is perfect— absolutely perfect. I will not take the responsibility to touch it. Mademoiselle will be the most beautiful bride, and she will have the most beautiful dress—of a perfection of a simplicity! One would say a statue of the antique!’ Her short, stout figure came into the mirror—a hundred Mirabelles going away to a vanishing point, all black, all wonderfully corseted, with waving hands and a torrent of words.

Sybil Dryden nodded.

‘Yes, it’s good,’ she said, in her calm, unhurried way.

She stood up and came into the picture too, another black figure but a slim one. She carried herself with distinction. Everything about her was just as it should be, from the faultless waves just touched with grey at the temples to the slender arch of the foot. The black coat and skirt conveyed no suggestion of mourning. There was a flash of diamonds in the lace at the throat. The small hat achieved just the right note of restrained elegance, endlessly repeated by the mirrors.

Hundreds of Aunt Sybils… Lila saw them in a swirling mist. She heard Mirabelle exclaim, and the mist broke into a shower of sparks.

Lady Dryden was nothing if not efficient. She caught the swaying figure as it fell, and since a white sheet had been spread on the floor of the fitting-room, the wedding-dress took no harm.