The James Bond Bedside Companion (27 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

J

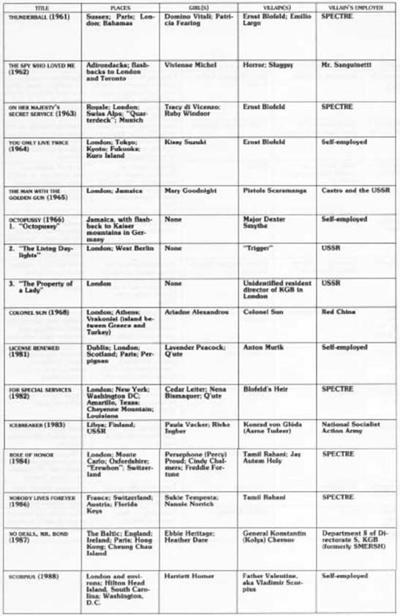

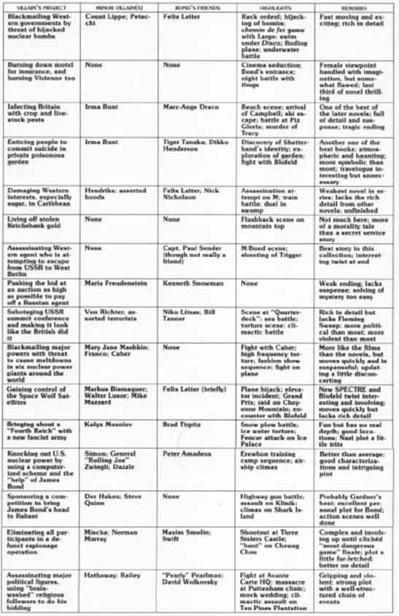

ames Bond was introduced to the world in 1953 with the publication of CASINO ROYALE. Fleming had predicted his first novel to be "the spy story to end all spy stories," but had no idea how accurate the prediction was, or what was to follow. In all, Ian Fleming wrote twelve James Bond novels and two collections of short stories. The series was continued after Fleming's death by Kingsley Amis (under the pseudonym of Robert Markham) with COLONEL SUN, and most recently, by John Gardner with LICENSE RENEWED, FOR SPECIAL SERVICES, and ICEBREAKER. Examining the series as a whole, a special world was indeed created—a landscape of fantasy and adventure to which readers could escape. Fleming himself admitted that he wrote "unashamedly for pleasure and money." He said the books were written for "warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes or beds." But the oeuvre deserves closer study because Fleming's style is unique, and the development of the James Bond character throughout the series is fascinating. The books should be examined chronologically, because there is a definite continuity from one novel to the next. Fleming's growth as a writer is apparent in comparing later novels with earlier ones.

Fleming's series can be divided into two groups: the early novels (CASINO ROYALE, 1953, through FOR YOUR EYES ONLY, 1960) and the later novels (THUNDERBALL, 1961, through OCTOPUSSY, published posthumously in 1966.) The early novels have an engaging style that concentrates on mood, character development, and plot advancement. In the later novels, Fleming injected more "pizzazz" into his writing—his work became richer in detail and imagery. By the time THUNDERBALL was published in 1961, Fleming had truly become a master storyteller; he was painting images with exacting detail and creating sweeping suspense. The only later novel which does not fit this bill is the last, THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN, published posthumously in 1965. The later novels also have a peculiar tone not found in the early ones: a feeling of imminent disaster and despair. This is perhaps because these later novels were written when Fleming's health was failing—he had suffered his first heart attack in 1961. His own feelings of "bodily decay" crept into the books.

But the series is

not

without humor, as many critics have complained. The novels are full of Ian Fleming's sense of humor, which can be cynical, melodramatic, and sly. It is the character of James Bond

himself

who is without humor. The humor is in the writing. For example, most of the meals James Bond eats do not exist. The so-called "Beef Brizzola" which Felix Leiter insists James Bond order at Sardi's in DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER is an invented dish. Fleming often pulls the reader's leg with his celebrated menus. The villains' obligatory "Welcome to Doomsday" speeches are another giveaway that the novels are not to be taken in total seriousness. Just try reading one of the speeches, Dr. No's, for example, aloud.

STYLE

P

erhaps the most striking stylistic element of the Fleming novels is their ability to sweep the reader along from chapter to chapter at a breakneck pace. Fleming once said that if his novels failed to do this, he would consider himself an unsuccessful writer. The important thing, he maintained, was to keep the plot moving. Fleming would sit at his desk at Goldeneye and type the entire novel without looking back at what he'd written. By driving through the initial story, Fleming established a fast, urgent pace. Hooks at the end of chapters were added to pull the reader into the next. Only once or twice does the "Fleming Sweep" fail in the series.

Another major stylistic element is the almost fanatical detail—especially trivial detail: brand names of objects; technical data about gadgets; specific ingredients of foods and drinks; and minute descriptions of scenic surroundings. Kingsley Amis, in his excellent book,

The James Bond Dossier,

calls this stylistic element "Fleming Effect." Fleming is so convincing in his descriptions that the reader rarely questions the factual accuracy of the detail. Only those with fanatical expertise have raised objections over some of the more blatant errors Fleming made. (And Fleming always seemed to enjoy

when a mistake was pointed out to him; witness the

case with Geoffrey Boothroyd.) All of this can be attributed to Fleming's experience as a journalist. Fleming's prose is rich and colorful, painting distinct and

believable

images. It's not important, really, whether the facts are right. The details are there merely to heighten the realism of the action.

Structure in Fleming's novels usually follows a specific formula. In most cases, the novel begins with a "teaser" chapter: the scene is set in the middle of the story, with Bond already on a designated assignment. The second chapter then flashes back to the beginning, as Bond receives his orders from his crusty old chief, M. The story then proceeds until it catches up with the opening chapter. The first part of the novel includes clue gathering, chance encounters with the villain and/or his henchmen, and the development of the romantic interest. The middle of the story usually involves a journey to the villain's headquarters which almost always leads to Bond's capture. The climax of the story involves, in Kingsley Amis' words, Bond being "wined and dined, lectured on the aesthetics of power, and finally tortured by his chief enemy" (three of Fleming's favorite situations). But Bond manages to make the villains eat their words by the novel's end. In seven of the books, Bond returns from his mission via the hospital. But his ordeal is worth it, for Bond usually ends up with a girl in his arms on the last page.

Only a few times does Fleming depart from his formula, choosing instead to experiment with the structure. Oddly enough, the results are some of the most interesting novels in the series (FROM RUSSIA, WITH LOVE; THE SPY WHO LOVED ME; and YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE). CASINO ROYALE, the first novel, is quite different from the basic Fleming formula, as well. The structure of each novel is discussed in its own section.

THEMES

T

he most obvious theme, of course, recurring throughout the Bond series is that of Good vs. Evil. The image of Saint George and the dragon is actually alluded to no less than three times. Fleming provides an entire chapter on the philosophies of Good and Evil in CASINO ROYALE, and YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE is an allegorical novel told in epic terms. In this later novel, James Bond represents all that is Good while his archenemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, represents everything that is Evil.

This theme accounts for why the Bond books are so popular. Wish fulfillment, character identification,

you name the terms; what the reader ultimately finds

attractive in the books is the vanquishing of Evil by Good, and the ease with which the reader can identify with the action. Fleming's treatment of his major character allows the reader to slip into James Bond's persona and view the world through his eyes. Of course, other elements enter into it—the attraction of the adventures (locales, characters, etc.), the women, and the novel's general embrace of worldly pleasures.

Another strong recurring theme is gambling, not only the casino variety, but in day-to-day situations. Fleming, a serious gambler, brought into the novels the essence of challenges in decision making. Bond takes risks in almost everything he does. Many times he takes a chance on a hunch or intuition—and sometimes the gamble doesn't pay off. For instance, Bond recklessly weighs the odds against Dr. No's dragon tank and orders his companion, Quarrel, to help him fight it with nothing but pistols. Quarrel ends up burned to death while Bond and his female friend are captured. Bond doesn't believe in luck—he states this explicitly in CASINO ROYALE —he "only bets on even chances." The Plot of FROM RUSSIA, WITH LOVE involves a gamble on Bond's part (as well as the Secret Service) to trust Tatiana Romanova, who claims she is in love with him. She will give the British a coveted secret coding machine belonging to the Russians if Bond will come and take her to the West Bond gambles when he hides Goldfinger's plans for the robbery of Fort Knox under a toilet seat in an airplane, hoping that an attendant will find the piece of paper and forward it to Felix Leiter. And, after learning that Scaramanga plans to kill him on a train ride, Bond gambles and allows himself to be taken along for the ride as a sitting duck. Fleming has taken the risks of the casino and put them into everyday life, or rather, the everyday life of James Bond.

Friendship is another recurring theme. In almost every novel, Bond has a male ally with whom he shares the adventure. In six cases, that ally turns out to be the American CIA agent, Felix Leiter, probably Bond's closest friend outside of England. Bond seems to depend on these male alliances, and the links between him and his friends are emotionally felt in the writing. This is especially true in LIVE AND LET DIE, when Leiter loses an arm and a leg to a shark, and in DOCTOR NO, when Quarrel is burned alive. Even though Bond ultimately accomplishes his mission alone (for instance, Leiter is forced to leave the underwater battle early in THUNDERBALL because of a malfunctioning breathing apparatus, the ally serves to add another dimension to Bond's character, and ultimately, to the thematic continuity of the novels.

Other themes crop up in individual novels, as do revenge and patriotism in YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE. Sometimes Fleming injects his books with cynicism, which isn't precisely a theme, but an element which reveals much of the author's view of the world. At times, the cynical tone is misanthropic, as in the first novel, CASINO ROYALE. Here, Fleming seems downright bitter. The endings of CASINO ROYALE, MOONRAKER, FROM RUSSIA, WITH LOVE, ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE, and YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE explore the tragic, the melancholic, and the wistful. Bond himself is a true cynic—he is suspicious of love, and is afraid of his emotions. It is Fleming's own view of the world which pervades his novels and creates distinctive moods.

Finally, one must accept the fact that the Bonds are fantasies. By no means did Fleming intend for them to be anything else. The extremely tongue-in-cheek sexual frivolity of the novels plays on the adolescent fantasies of sexual skill which mature readers have never wholly forgotten. These fantasies are most likely far more thrilling and sensational than the reader's reality. Male readers can live the adventures

through

Bond, and escape into a world where one is tough enough to withstand torture yet can retain enough energy to make love to a beautiful woman later. Female readers could imagine that they, too, were independent free spirits like the Bond women, unfettered by the duties of home and family—traveling to exotic places and meeting handsome spies. Once one has accepted the fact that Fleming is pulling the reader's leg and is laughing to himself, these fantasies and dreams can be enjoyed by any reader who is willing to allow his or her senses to be aroused.

CHARACTERS

J

ames Bond's character has been examined in an earlier section. An overview of the series reveals that Bond becomes more human with each successive novel. In CASINO ROYALE, Bond is such a cold, ruthless individual that the reader is barely able to identify with him. Not until MOONRAKER does Fleming begin to flesh out a "normal" life for Bond. Here, the reader is treated to scenes of Bond's daily office life and social outings. In FROM RUSSIA, WITH LOVE, a scene at Bond's flat is included, and the reader meets the agent's elderly Scottish treasure of a housekeeper, May. In GOLDFINGER, Fleming's prose has a stream of consciousness quality: in this novel, Bond's interior monologue allows the reader to discover the character's more personal thoughts.