The James Bond Bedside Companion (3 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

Both moved in top-drawer Mayfair: Maugham, Coward, and the satellite world of heartless literati. The Flemings, particularly Anne, were very close to Prime Minister Eden, much as the American jet set was close to President Kennedy. It was a fast, slippery track. It is worth mentioning that both Prime Minister Eden and President Kennedy came a cropper on it, as did Fleming, his son Caspar, and eventually Anne. However, it would be fatuous to suggest there was any causal relationship. All one can do is note that whatever his literary existence, James Bond appears as an evil talisman in the very real lives of people in his periphery. Eden's illness and his fleeing to Fleming's place, Goldeneye, has an overtone of

Appointment in Samara.

Jack Kennedy, professing his preference for James Bond, certainly imitated him to a degree no President had even remotely approached before. President Kennedy's death duel with Cuba's Castro has James Bond overtones.

I had thought I knew Ian Fleming thoroughly, in and out. Thus, I was surprised, and a trifle miffed with Ian, when I read John Pearson's book on Fleming. I was amazed to learn that Fleming had not graduated from either Eton or Sandhurst, which he certainly permitted and even encouraged me to believe. In fact, he even told me that on graduation from Sandhurst, he had selected the Black Watch as his regiment. I was also under the impression he left the Foreign Service for journalism. Actually, he had not; he never belonged to it. I was annoyed also, because his broken nose led me to believe that he had taken terrific physical punishment during his athletic years. I assumed his broken nose was acquired in amateur boxing or one of the collision sports. Once, however, when we playfully squared off, I perceived that he hadn't the slightest notion of the conventional boxing stance. "Egads," I said to him, "no wonder you've got a busted nose!" There is a certain intrinsic knowledge gained from physical damage which can only be learned by experience, which most civilians never learn, and never have to. Those who do experience it form a sort of freemasonry, a brotherhood, as it were, of those who have been badly hit, knocked unconscious, and managed to come back to life. This group was called by an appellation of the Old Frontier: "Fighting Men." I assumed that Fleming was a Fighting Man. Fighter he was, but a Fighting Man he was not: he was a very badly wounded civilian, both in life and in love. He lived a hard, emotional life, because unlike Fighting Men, he never emotionally accepted death—especially of his ideal love.

It is my belief and experience that most British and American boys receive a terrible emotional mauling in their first love affair because of the chivalry and Boy Scout ideals with which they are indoctrinated shortly after they can read: the Knights of Old, King Arthur, Sir Galahad. It seemed to me that Fleming was too badly wounded in his first love to talk about it. But I sensed there was some lissome, ivory-skinned girl with blue-black hair—for this is what he considered to be the ultimate type of beauty—off in some fir-clad hills in the idyllic Alpine snowlands, who was the cause of his deep wound. It seems to me that James Bond embodies Ian's revenge for the terrible hurt; Bond tumbles them into bed, leaves them with the memory of a savage ravishment which, ye gods, leaves them pining for Bond and forever bereft without him. This, of course, is the exact opposite of the ethereal "pure" love of the adolescent English and American boy. I think it is possible that Ian carried the image of the ideal damsel throughout his life, and found his adult ideal in Anne; that Anne was the ideal superwoman, the super-sophisticate, the toast of Mayfair, and the Madame de Stael of statesmanship and empires. This society is a twentieth-century version of

Vanity Fair.

It is dangerous, a maelstrom of descending disaster, and Anne and Ian got into its swirl when they were both old enough to know better. I suppose it is more accurate to say, she was already caught in it and he jumped in after her.

There is one thing, I think, that marks Ian's

modus operandi

: he mastered whatever he undertook. He was a first-class journalist, a magnificent administrator, a most excellent wordsmith, a writer who created his opposite, an upper-class knave, in Bond, an elegant cad, an amoral bastard, who performed every kind of crime, and with Ian's final, wry revenge on his class—of all things—in the service of Their Britannic Majesties! What a bitter twist!

Gresham's Law of the Twentieth Century is applicable to fields far wider than economics. Like bad currency, bad literature is driving out the good. If this be so, Ian Fleming's James Bond certainly gave the Gresham's Law of Literature a grand shove into the spotlight. Ian Fleming knew exactly what he was trying to do. Not the slightest presumption of innocence attaches to either his effort or the character of James Bond. His objective was the making of money. It made him a lot, but, ironically, not nearly as much as it made for others after his death. James Bond is no Sherlock Holmes, but as long as sexual fantasy exists (and it has existed from the Pompeiean friezes through

Fanny Hill

), James Bond will live on as a Popeye the Sailorman, a combination of the supermale and the Little Jack Horner of the Intelligence Services, who from here to eternity, will stick in his thumb and pull out a plum and say

what a smart boy am I

. Actually, in even the flaming character of Bond it can be seen that Ian Fleming was a great wordsmith and most excellent writer.

It so stunned me to find out that Ian hadn't graduated from Eton and Sandhurst, that I examined the pattern of his departures. There was a curious twist: he did not drop out until he had met the challenge. He had mastered the course but refused to cross the finish line. Having demonstrated he could win, he threw in his hand. That's what he probably did with his life: at the end, in pain, tired, and disillusioned, he said, "The hell with it, it's a bore. I've proven I can play the hand, I've won the pot—and now you can keep it." James Bond, who, in the novels, is often stricken with the malady of ennui, would probably have done the same thing had he been a real person. After all, what could be more ridiculous than a seventy-five-year-old James Bond?

Ernest L. Cuneo

Washington, D.C.

Primary reference sources for Parts One and Two were John Pearson's

The Life of Ian Fleming

and personal interviews conducted with several of Fleming's close friends and associates. Parts Three and Four draw from the novels. There is an abundance of quoted material from the books; hopefully, these "clips" will serve as a collection of memorable passages—"The Best of Bond," so to speak. Primary reference sources for Part Five were John Brosnan's

James Bond in the Cinema

,

Steven Jay Rubin's

The James Bond Films

,

Bondage

Magazine (published by the James Bond 007 Fan Club), and, of course, the films themselves. Finally, much trivia and information throughout the book was contributed by members of the James Bond 007 Fan Club and other Bond fans around the world.

To avoid confusion, all James Bond book titles and other books by Ian Fleming mentioned in the text are shown in small caps (GOLDFINGER), and all film and other book titles are italicized

(Goldfinger).

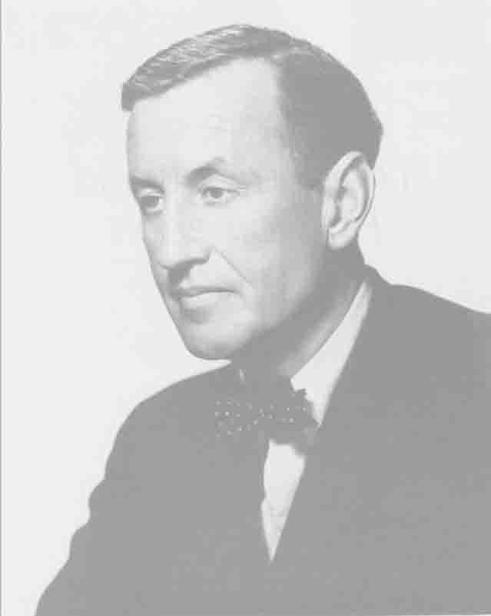

An early publicity shot of Ian Fleming, circa 1954. (Photo courtesy of owner.)

T

he James Bond phenomenon began one sunny morning in Jamaica as Ian Fleming pondered what to name the hero of a novel he was writing. Fleming said that he wanted "the dullest name he could find," and he discovered it on his coffee table. One of his favorite books,

Birds

of

the West Indies

,

was written by an ornithologist named James Bond. Promptly christening his hero, Fleming began the novel which would change the direction of British spy literature.

It was January 1952. Ian Fleming was Foreign Manager for Kemsley Newspapers, the huge organization which owned the London

Sunday Times

and dozens of other newspapers throughout Britain. He had accepted the job in 1945 with the special condition that he be allowed two months paid vacation per year. Since the war, Fleming had spent those two months every year at his retreat in Oracabessa, Jamaica. The three-bedroom house was called "Goldeneye," which he had named after one of his favorite American novels,

Carson McCullers' Reflections in a Golden Eye.

"Goldeneye" was also a code name for a wartime operation conceived and led by Fleming while he was Assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence. (A personality sketch and detailed account of Fleming's life prior to 1952 appears in Part Two.)

This particular January, Ian Fleming's mind was on a number of matters; of most importance was his upcoming marriage to Anne Rothermere, whose divorce from Lord Esmond Rothermere was to be announced on February 8. Fleming had been a confirmed bachelor all his life. There are several possible explanations for his decision to write his first novel, but the reason he gave was to relieve his mind from "the shock of getting married at the age of forty-three." Another reason could be that he was simply tired of being "Peter Fleming's younger brother." Though Ian Fleming was a journalist, he had never written anything longer than an article for the

Sunday Times.

Peter Fleming was already a well respected author, and up to this point, Ian Fleming had avoided competing with him.

For whatever reason, Fleming needed a distraction. It was Anne who suggested he write something to amuse himself. The atmosphere at Goldeneye provided the perfect conditions. Amuse himself is precisely what he did. The book that Ian Fleming wrote in 1952 was CASINO ROYALE, the first adventure featuring a secret agent named James Bond.

At Goldeneye, Fleming initiated his standard operating procedure for writing the Bond books. Each day he rose about 7:30 a.m. and swam in his private cove. After returning for breakfast, his favorite meal of the day, he relaxed until 10:00 a.m. Then he would begin to type, using folio paper (forty-four lines to a full page, double-spaced). (Sometimes the paper would slip in the typewriter on the last line, invariably causing the row of words to slope down to the right.) Fleming composed at the typewriter as he worked. He finished around noon, after which he would sun himself or go snorkeling among the coral. After an afternoon nap, Fleming resumed work at the typewriter for about an hour. A day's work produced about 2,000 words. Next came supper, and afterwards, perhaps a relaxing visit from an island neighbor (such as Noel Coward). The next day the entire routine would be repeated, and so on, until the 70 to 80,000 words were on paper. Fleming never looked back at what he'd written. He emphasized that it was important to keep the plot

moving

,

and by dashing through the first draft in this way, he created the "sweeping" quality of the James Bond novels. Only when he stopped over in New York or returned to England would he look over his manuscript and revise, polish, and embellish. Using a ballpoint pen, he corrected words and passages. Sometimes he added inserts written in longhand on pieces of personal stationery. During the following months, he would add the rich detail associated with the Bond books, title the chapters, and finally turn in the finished manuscript to his publishers, Jonathan Cape, Ltd., in the fall.

Goldeneye, Oracabessa, Jamaica. Ian Fleming built his winter retreat in 1945 and spent every January and February there until his death in 1964. (Photo by Mary Slater.)