The Kennedy Brothers: The Rise and Fall of Jack and Bobby (33 page)

Read The Kennedy Brothers: The Rise and Fall of Jack and Bobby Online

Authors: Richard D. Mahoney

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Political, #History, #Americas, #20th Century

Their golden year was 1963. Here newly elected senator Edward Kennedy poses outside the Oval Office with his older brothers.

Courtesy of the John F Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

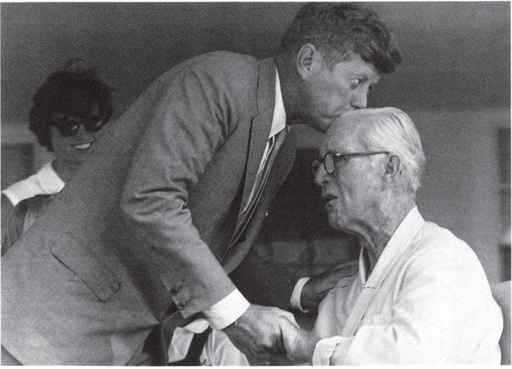

The president visits his stricken father in Hyannis Port, a rare public display of affection. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

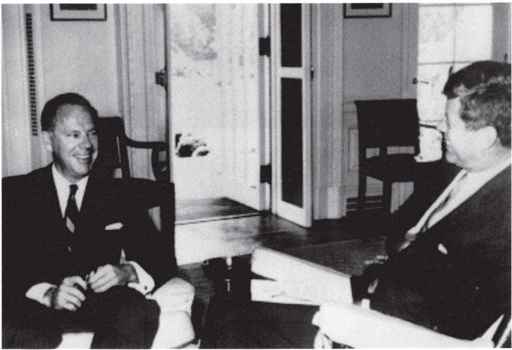

Ambassador William Mahoney, the author’s father, discusses the 1964 elections with President Kennedy on November 19, 1963. Courtesy of William Mahoney.

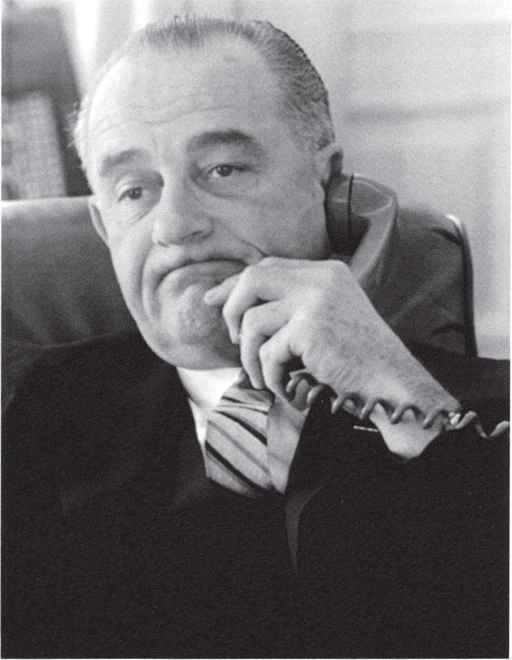

LBJ thought JFK’s assassination was “divine retribution.” Photo by Yoichi R. Okamoto, courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library.

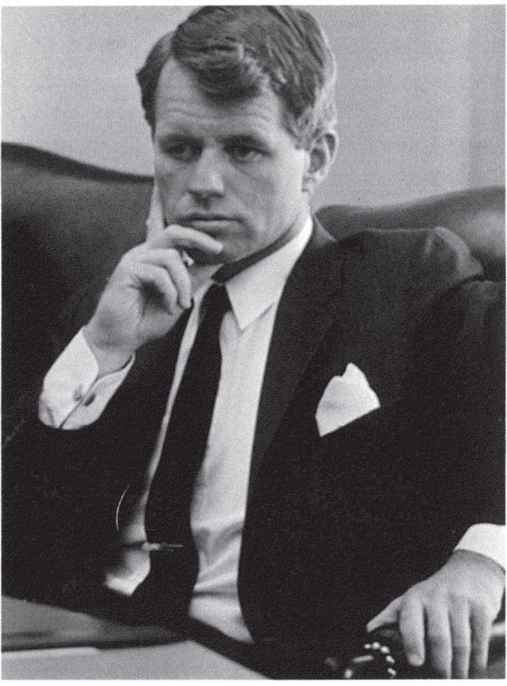

January 1964: a wounded and bewildered man. Photo by Yoichi R. Okamoto, courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library.

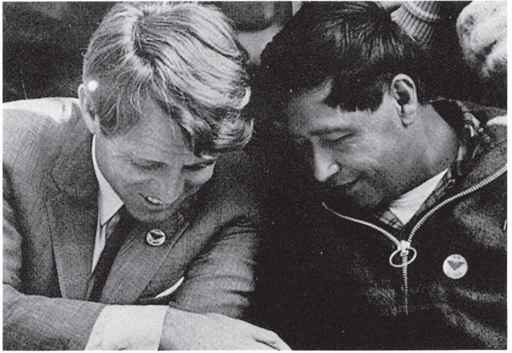

BELOW: Bobby joins Cesar Chavez at the Mass of Thanksgiving held in March 1968 in Delano, California, to celebrate the end of the labor leader’s fast. For all their differences of wealth and power, they were much alike.

“So far he’s run with the ghost of his brother,” Senator Eugene McCarthy said about Bobby’s run for the presidency. “Now we’re going to make him run against it. It’s purely Greek: he either has to kill him or be killed by him.”

The next day, Thursday, new photographic evidence brought bad news: between sixteen and thirty-two missile sites were now under construction and estimates were that some would be ready to fire their missiles within a week. The hawks, now led by the grand old man of containment, former secretary of state Dean Acheson, pressed Kennedy hard. The blockade, they argued, would not “remove the missiles and would not even stop the work from going ahead on the missile sites themselves. [A]ll we would be doing with a blockade would be closing the door after the horse had left the barn.” If we blockaded Cuba, the hawks argued, the Soviets would blockade Berlin where their conventional forces were overwhelmingly superior. The place to stop aggression was where it started, where our conventional power was preeminent. A surprise attack could knock out the missiles before they could be armed with warheads.

196

(Soviet and Cuban principals later revealed that there were in fact warheads on the island during the crisis.)

Bobby, who was informally chairing the meeting in his brother’s absence, termed this a “Pearl Harbor in reverse” and later explained the gravamen of his belief: “I could not accept the idea that the United States would rain bombs on Cuba, killing thousands and thousands of civilians in a surprise attack. Maybe the alternatives were not very palatable, but I simply did not see how we could accept that course of action for our country.”

197

Acheson was contemptuous of this and mocked the attorney general, asking whether it was necessary “to adopt the early nineteenth-century methods of having a man with a red flag walk before a steam engine to warn cattle and people to stay out of the way.” Acheson was sufficiently exercised by the younger Kennedy’s “moralizing” that he asked to see the president alone that evening. When Jack himself brought up the Pearl Harbor analogy, Acheson told him it was a “silly” way to analyze the problem: “It is unworthy of you to talk that way.”

198

By October 18, Ex Comm appeared more or less split between the blockade and the air strike. But the next day, with the president in Chicago on what was being called a fund-raising trip, Bundy made a determined run at pushing through the air strike. He said that he had spoken to the president that morning, intimating that Kennedy was now leaning toward an air strike. After Bundy finished, Acheson weighed in. Then the other hawks, Dillon, McCone, and Taylor, ticked off their support of the strike. Bobby, now sitting, noted with a grin that he too had talked to the president that morning and that “it would be very, very difficult indeed for the president if the decision were to be for an air strike, with all the memory of Pearl Harbor and with all the implications this would have for us in whatever world there would be afterward. For 175 years we had not been that kind of country. A sneak attack was not in our traditions.”

199

The implicit message in what he said could not be mistaken. Bobby was speaking for his brother, and his brother would not accept an air strike. If there was to be an air strike, it would come later, not sooner. But there was something about the way he made the statement that also impressed his audience, something that Douglas Dillon later called his “quiet and intense passion.” “I felt I was at a real turning point in history,” Dillon said. “The way Bobby Kennedy spoke was totally convincing to me.” It was as if his simplicity of communication and the intensity of the emotion behind his words imparted a special power to them.

Bobby later wrote that “pressure does strange things to a human being, even to brilliant, self-confident, mature, experienced men. For some it brings out characteristics and strengths that perhaps they never knew they had, and for others the pressure is too overwhelming.”

200

But if this were true of the other men meeting around the clock (Rusk had suffered something of a mental collapse), the effect of pressure on Bobby was known, especially by his brother. At every crisis point in his life — the McClellan Committee hearings, Jack’s campaigns in 1952 and 1960, the successive civil rights crises of 1961 and 1962 — he drew strength from the storm, remaining razor-alert and indefatigable.

201

By October 18, Ex Comm was ready with its recommendation to the president, who flew home from Chicago. Back in the White House, Bobby sat by the side of the pool and watched his brother do laps for a half hour. While Jack did the breast-stroke, they talked. Later, they walked over together for a full-dress, two-hour meeting of the National Security Council.

McNamara presented the arguments for a blockade, Taylor for the air strike. (Acheson did not attend, protesting what he regarded as a foreordained decision). The president had indeed decided on the blockade, but not before carefully canvassing the more egomaniacal members of the Joint Chiefs. When General Curtis LeMay took on the president over the advisability of the blockade, Kennedy coldly cut him off. Afterward, Jack said to O’Donnell: “These brass hats had one great advantage in their favor. If we do what they want us to do, no one of us will be alive later to tell them they were wrong.”

202

After the meeting, which had taken place in the Oval Room, the president walked out onto the small, second-story porch, sunlit and cool in the late October afternoon. Sorensen and Bobby joined him there, as did a few others from time to time. As he gazed out at the autumn panorama, Jack talked, as Sorensen later wrote, “as he almost never talked,” of life and death. He calculated the odds of nuclear war, which he thought were about one in three, and about the killing of children if this were to pass. “If it weren’t for them, for those who haven’t even lived yet, these decisions would be easier.” Then in his abrupt way, he turned to Sorensen. “I hope you realize that there’s not enough room for everyone in the White House bomb shelter.” Jack, Bobby, and Sorensen joked about who was on the list of invitees and who wasn’t.

203

The crisis revealed the essence of Jack Kennedy: his sense of theater, his astringent realism and distaste for the moral posture, his profound reservations about the military, his view of history as a march of folly toward war, and, most of all, his profound dependence on his brother.

That evening, the president went to dinner at the home of journalist Joe Alsop in Georgetown. Another guest was Charles Bohlen, former ambassador to the Soviet Union, who was en route to Paris to serve as American ambassador. Kennedy took Bohlen out into the garden and spoke with him for about twenty-five minutes. Later, over dinner, the president asked Bohlen what the Russians had done in the past when backed into a corner. Susan Alsop was to remember Kennedy asking that question twice. After going to bed, she said to her husband, “Darling, there’s something going on. I may be crazy but there’s something going on.” “I think you’re crazy,” Alsop replied.

204