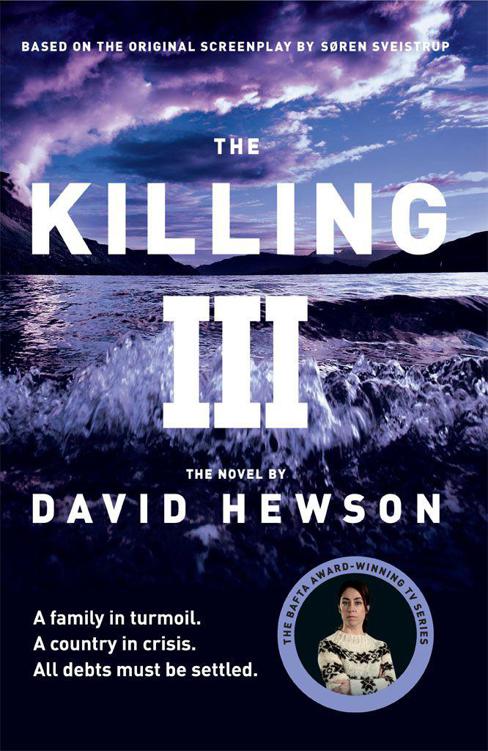

The Killing 3

Authors: David Hewson

Principal Characters

Copenhagen Police

Sarah Lund –

Vicekriminalkommisær, Homicide

Lennart Brix –

Head of Homicide

Mathias Borch –

Investigating officer, Politiets Efterretningstjeneste (PET); the internal national security intelligence agency, a separate arm of the police

service

Ruth Hedeby –

Deputy Director

Tage Steiner –

Lawyer for internal affairs

Asbjørn Juncker –

Detective, Homicide

Madsen –

Detective, Homicide

Dyhring –

head of PET

Politics

Troels Hartmann –

Prime Minister, heading the Liberal Party

Rosa Lebech –

leader of the Centre Party

Anders Ussing –

leader of the Socialist Party

Morten Weber –

Hartmann’s political adviser

Karen Nebel –

Hartmann’s head of media relations

Birgit Eggert –

Finance Minister

Mogens Rank –

Justice Minister

Kristoffer Seifert –

former Socialist Party worker

Per Monrad –

Ussing’s campaign manager

Zeeland

Robert Zeuthen –

heir to the Zeeland business empire

Maja Zeuthen –

Robert’s estranged wife

Niels Reinhardt –

Robert Zeuthen’s personal assistant

Emilie Zeuthen –

the Zeuthens’ daughter, aged nine

Carl Zeuthen –

the Zeuthens’ son, aged six

Kornerup –

CEO of Zeeland

Others

Vibeke –

Lund’s mother

Mark –

Lund’s son

Eva Lauersen –

Mark’s girlfriend

Carsten Lassen –

a doctor at the university hospital

Peter Schultz –

deputy prosecutor

Lis Vissenbjerg –

pathologist at the university hospital

Nicolaj Overgaard –

former Jutland police officer

Louise Hjelby –

girl in Jutland

Wednesday 9th November

They always gave her the young ones. This time he was called Asbjørn Juncker, twenty-three years old, newly made up to detective from trainee, now gleefully sorting

through the skeletons of wrecked cars in a run-down scrapyard on the edge of the docks.

‘There’s an arm here!’ he cried as he rounded the rusting husk of a long-dead VW Beetle. ‘An arm!’

Madsen had a team of men moving out to sweep the area. He looked at Lund and sighed. Asbjørn had turned up at the Politigården from the provinces that morning, assigned to homicide.

Fifteen minutes later while Lund was half-listening to the news – the financial crisis, more about the coming general election – the yard called to say they’d found a body. Or

more accurately parts of one scattered among the junk. Probably a bum from the neighbouring shantytown in the abandoned dock. Someone who’d scrambled over the fence looking for something to

steal, fallen asleep in a car, died instantly the moment it was picked up by one of the gigantic cranes.

‘Funny spot to take a nap,’ Madsen said. ‘The grab sliced him in half. Then he seems to have got cut about a bit more. The crane operator choked on his coffee when he saw what

was happening.’

Autumn was giving up on Copenhagen, getting nudged out of the way by winter. Grey sky. Grey land. Grey water ahead with a grey ship motionless a few hundred metres off shore.

Lund hated this place. During the Birk Larsen murder she’d come here looking for a warehouse belonging to the missing girl’s father. Theis Birk Larsen was now out of jail after

serving his sentence for killing the man he thought murdered his daughter. Back in the removals business from what Lund had heard. Jan Meyer, her partner who got shot during that investigation, was

still an invalid, working for a disabled charity. She’d gone nowhere near him, or the Birk Larsens, even though that case was still unsettled in her own head.

She looked across the bleak water at the dead ship listing at its final anchor. Ghosts still hung around her murmuring sometimes. She could hear them now.

‘You’re not really going to take a job in OPA, are you?’ Madsen asked.

The Politigården was always rife with gossip. She should have known it would get out.

‘I get a medal for twenty-five years’ service today. There’s only so much of your life you can spend out in the freezing cold looking at pieces of dead people.’

‘Brix doesn’t want to lose you. You’re a pain in the arse sometimes, but no one does. Lund—’

‘What?’ Juncker squealed, clambering through the wreckage. ‘You’re going to count paper clips all day long?’

OPA – Operations, Planning and Analysis – did rather more than that but she wasn’t minded to tell him. Something about Juncker reminded her of Meyer. The cockiness. The

protruding ears. There was an odd, affronted innocence too.

‘They said I was going to work with someone good . . .’ the young cop started.

‘Shut up Asbjørn,’ Madsen told him. ‘You’re doing that already.’

‘I’d also like to be called Juncker. Not Asbjørn. Everyone else gets called by their last name.’

They’d recovered six pieces of a half-naked, middle-aged man’s body. Juncker’s was the seventh.

There was an old wheelbarrow next to the Beetle. She asked the scrapyard manager for a price. He seemed a bit surprised but came up with one quickly enough. Lund handed over a few notes and told

Juncker to put it in the boot of her car.

His hands went to his hips.

‘Is someone going to look at my arm or not?’

Stroppy young men. She was getting used to them. Mark was supposed to come round for dinner that evening with his girlfriend. First visit to her new home, a tiny wooden cottage on the edge of

the city. She wondered if he’d make it or invent one more excuse.

Juncker nodded at the photographer now taking pictures where he’d been, then stuck a finger in the air like a schoolboy counting off a list.

‘There’s no ID. But he’s got a gold ring and some tattoos. Also the skin’s wrinkled like it’s been in water.’ He pointed at the flat, listless harbour.

‘In there.’

Lund looked at the scrapyard man, then the derelict area beyond the nearest wall.

‘That used to be warehouses,’ she said. ‘What’s it now?’

He had a sad, intelligent face. Not what she expected in a spot like this.

‘It was one of Zeeland’s main terminals. The warehouses were just a favour on the side to the little people.’ He shrugged. ‘Not so many little people any more. And just a

few containers going through. They shut up most of it the moment things turned bad. Almost a thousand men gone overnight. I used to manage the loading side of things. Worked there ever since I left

school . . .’

He didn’t like talking about this. So he lugged the wheelbarrow over to Lund’s car, opened the boot, and set it next to a couple of rosebushes waiting there in pots.

‘He’s been in the water. He’s got tattoos,’ Juncker repeated. ‘There’s marks on his arm that look like they came from a knife.’

The shantytown next door was a sprawling shambles of corrugated iron and rusting trucks and caravans set on the car park to the old dockyard. That was never there when she was hunting the

murderer of Nanna Birk Larsen.

‘He was a bum who wandered in here looking for something to nick,’ Madsen cut in. ‘We’ll take the photos. You can try writing up the report if you like. I’ll check

it for you.’

Juncker really didn’t like that.

‘There’ll be trouble if we don’t look busy round here,’ he said.

‘Why?’ Lund asked.

‘Politicians on the way.’ He nodded at the scrapyard manager who was looking closely at Lund’s plants, seemingly unimpressed. ‘He told me. They’re doing a photo

opportunity with all them homeless people.’

‘Bums don’t have votes,’ Madsen grumbled.

‘They don’t have gold rings either,’ Juncker pointed out. ‘Did you hear what I said? The big shots are going to talk to the men left in the dockyard. Troels

Hartmann’s coming they reckon. Here in an hour.’

Ghosts.

This place had just acquired a new one. Hartmann had been a suspect in the Birk Larsen case, one whose ambition and arrogance almost ruined his career.

Pretty boy

, Meyer called him. The

handsome Teflon man of Copenhagen politics. As soon as he was cleared he scored an unlikely victory to become the city’s mayor. Then two and a half years ago, after a campaign racked by

vitriol about the collapsing economy, he’d emerged victor in a general election, becoming the Liberals’ Prime Minister leading a new coalition.

‘Hartmann was in that big case of yours,’ Juncker added. ‘I remember that.’

It seemed like yesterday.

‘Were you here then?’ she asked without thinking.

Asbjørn Juncker laughed out loud.

‘Here? That was ages ago. I read about it when I was in school. Why do you think I joined the police? It sounded—’

‘Six years,’ Madsen said. ‘That’s all.’

Long ones, Lund thought. Soon she’d be forty-five. She had a little place of her own. A dull, simple, enclosed life. A relationship to rebuild with her son. No need of bitter memories from

the past. Or fresh nightmares for the future.

She told Madsen to keep on looking and make sure nothing untoward came near the media or the approaching political circus. Then she drove back to the Politigården, a small bay tree

bouncing around in the footwell of the passenger seat, changed into her uniform, the blue skirt, blue jacket, watched all the others turning up for their long service medals. They seemed so much

older than she felt.

Brix came and nagged about the OPA job.

‘I need you here,’ he said. The tall boss of homicide eyed her up and down with his stern and craggy face. ‘You don’t look right dressed like that.’

‘How I dress is my business. Will you give you me a good reference?’ She was anxious about this. ‘I know there are things in the past they won’t like. You don’t

need to dwell on them.’

‘OPA’s where people go to retire. To give up. You never—’

‘Yes. I know.’

He muttered something she couldn’t hear. Then, ‘Your tie’s not straight.’

Lund juggled with it. Brix was immaculate in his best suit, fresh pressed shirt, everything perfect. The more he stared, the worse the tie got.

‘Here,’ he said and did it for her finally. ‘I’ll talk to them. You’re making a mistake. You know that?’

The forbidding red-brick castle called Drekar was once a small hunting lodge owned by minor royalty. Then Robert Zeuthen’s grandfather bought it, enlarged the place,

named his creation after the dragon-headed longships of the Vikings. A man intent on founding a dynasty, he loved the fortress in the woods. Its exaggerated battlements, the sprawling, manicured

grounds running down to wild woodland and the sea. And the ornate extended gargoyle he built at the seaward end, fashioned in the fantastic shape of a triumphant dragon, symbol of the company he

created.

The ocean was never far away from the thoughts of the man who built Zeeland. Starting in the 1900s Zeuthen had transformed a small-time family cargo firm into an international enterprise with a

shipping fleet running to thousands of vessels. Zeuthen’s own father, Hans, had carried on the expansion when he inherited the company. Finance and IT subsidiaries, consulting arms, hotels

and travel firms, even a domestic retailing chain came to bear the Zeeland logo: three waves beneath the Drekar dragon.