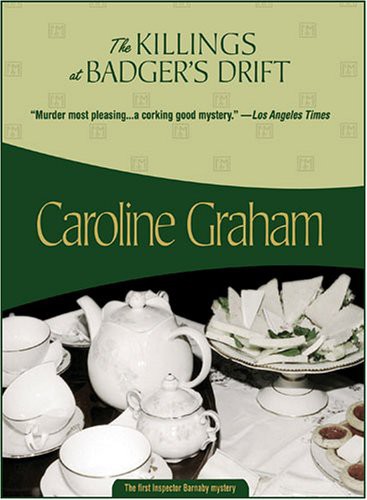

The Killings at Badger's Drift

Read The Killings at Badger's Drift Online

Authors: Caroline Graham

Tags: #Crime, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Fiction

The Killings at Badgers Drift

CAROLINE GRAHAM

headline

Copyright © 1987 Caroline Graham

The right of Caroline Graham to be identified as the Author of

the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law,

this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted,

in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in

writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in

accordance with the terms of licences issued by the

Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2010

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7553 7606 3

This Ebook produced by Jouve Digitalisation des Informations

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Table of Contents

Praise for Caroline Graham:

‘The best-written crime novel I’ve read in ages’ Susan Green,

Good Housekeeping

‘An exemplary crime novel’

Literary Review

‘Hard to praise highly enough’

The Sunday Times

‘Lots of excellent character sketches . . . and the dialogue is lively and convincing’

Independent

‘Graham has the gift of delivering well-rounded eccentrics, together with plenty of horror spiked by humour, all twirling into a staggering

danse macabre

’

danse macabre

’

The Sunday Times

‘A wonderfully rich collection of characters . . . altogether a most impressive performance’

Birmingham Post

‘Everyone gets what they deserve in this high-class mystery’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Wickedly acid, yet sympathetic’

Publishers Weekly

‘Excellent mystery, skilfully handled’

Manchester Evening News

‘One to savour’

Val McDermid

‘Her books are not just great whodunits but great novels in their own right’

Julie Burchill

‘Tension builds, bitchery flares, resentment seethes . . . lots of atmosphere, colourful characters and fair clues’

Mail on Sunday

‘A mystery of which Agatha Christie would have been proud . . . A beautifully written crime novel’

The Times

‘Characterisation first rate, plotting likewise . . . Written with enormous relish. A very superior whodunnit’

Literary Review

‘Swift, tense and highly alarming’

TLS

‘The classic English detective story brought right up to date’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Enlivened by a very sardonic wit and turn of phrase, the narrative drive never falters . . . a most impressive performance’

Birmingham Post

‘From the moment the book opens it is gripping and horribly real because Ms Graham draws her characters so well, sets her scenes so perfectly’

Woman’s Own

‘An uncommonly appealing mystery . . . a real winner’

Publishers Weekly

‘Guaranteed to keep you guessing until the very end’

Woman

‘Lots of excellent character sketches . . . and the dialogue is lively and convincing’

Independent

‘A witty, well-plotted, absolute joy of a book’

Yorkshire Post

‘Switch off the television and settle down for an entertaining read’

Sunday Telegraph

‘A pleasure to read: well-written, intelligent and enlivened with flashes of dry humour’

Evening Standard

‘Read her and you’ll be astonished . . . very sexy, very hip and very funny’

Scotsman

‘The mystery is intriguing, the wit shafts through like sunlight . . . do not miss this book’

Family Circle

‘A treat . . . haunting stuff’

Woman’s Realm

Caroline Graham was born in Warwickshire and educated at Nuneaton High School for Girls, and later the Open University. She was awarded an MA in Theatre Studies at Birmingham University, and has written several plays for both radio and theatre, as well as the hugely popular and critically acclaimed Detective Chief Inspector Barnaby novels, which were also adapted for television in the series

Midsomer Murders

.

Midsomer Murders

.

To Christianna Brand

With grateful thanks

for all her help and encouragement

With grateful thanks

for all her help and encouragement

And appetite, an universal wolf,

so doubly seconded with will and power,

Must make perforce an universal prey,

And last eat up himself.

so doubly seconded with will and power,

Must make perforce an universal prey,

And last eat up himself.

Troilus and Cressida

Act 1, Scene 3

Act 1, Scene 3

Prologue

She had been walking in the woods just before teatime when she saw them. Walking very quietly although that had not been her intention. It was just that the spongy underlay of leaf mould and rotting vegetation muffled every footfall. The trees, tall and packed close together, also seemed to absorb sound. In one or two places the sun pierced through the closely entwined branches, sending dazzling shafts of hard white light into the darkness below.

Miss Simpson stepped in and out of these shining beams peering at the ground. She was looking for the spurred coral root orchid. She and her friend Lucy Bellringer had discovered the first nearly fifty years ago when they were young women. Seven years had passed before it had surfaced again and then it had been Lucy who had spotted it, diving off into the undergrowth with a hoot of triumph.

Their mock feud had developed from that day. Each summer they set out, sometimes separately, sometimes together, eager to find another specimen. Hopes high, eyes sharp and notebooks and pencils at the ready they stalked the dim beechwoods. Whoever spotted the plant first gave the loser, presumably as some sort of consolation prize, a spectacularly high tea. The orchid flowered rarely and, due to an elaborate system of underground rhizomes, not always in the same place twice. Over the last five years the two friends had started looking earlier and earlier. Each was aware the other was doing so; neither ever mentioned it.

Really, thought Miss Simpson, parting a clump of bluebells gently with her stick, another couple of years at this rate and we’ll be coming out when the snow’s on the ground.

But if there was any justice in the world (and Miss Simpson firmly believed that there was) then 1987 was her turn. Lucy had won in 1969 and 1978, but this year . . .

She tightened her almost colourless lips. She wore her old leghorn hat with the bee veil pushed back, a faded Horrockses cotton dress, wrinkled white lisle stockings and rather baggy green-stained tennis shoes. She was holding a magnifying glass and a sharp stick with a red ribbon tied to it. She had covered almost a third of the wood, which was a small one, and was now working her way deep into the heart. Ten years could easily pass between blooms but it had been a wet cold winter and a very damp spring, both propitious signs. And there was something about today . . .

She stood still, breathing deeply. It had rained a little the evening before and this had released an added richness into the warm, moist air - a pungent scent of flowers and verdant leaves with an undernote of sweet decay.

She approached the bole of a vast oak. Scabby parasols of fungus clung to the trunk and around the base was a thick clump of hellebores. She circled the base of the tree, staring intently at the ground.

And there it was. Almost hidden beneath flakes of leaf mould, brown and soft as chocolate shavings. She moved the crumbs gently aside; a few disturbed insects scuttered out of the way. It gleamed in the half light as if lit from within. It was a curious plant: very pretty, the petals springing away from the lemon calyx like butterfly wings, delicately spotted and pale fawny yellow but quite without any trace of green. There were no leaves and even the stem was a dark, mottled pink. She crouched on her thin haunches and pushed the stick into the ground. The ribbon hung limp in the still air. She leaned closer, pince-nez slipping down her large bony nose. Tenderly she counted the blooms. There were six. Lucy’s had only had four. A double triumph!

She rose to her feet full of excitement. She hugged herself; she could have danced on the spot. Nuts to you Lucy Bellringer, she thought. Nuts and double nuts. But she did not allow the feelings of triumph to linger. The important thing now was the tea. She had made notes last time when Lucy had been out of the room refreshing the pot and, whilst not wishing to appear ostentatious, was determined to double the choice of sandwiches, have four varieties of cake and finish off with a home-made strawberry water ice. There was a large bowl of them, ripe to bursting, in the larder. She stood lost in blissful anticipation. She saw the inlaid Queen Anne table covered with her great aunt Rebecca’s embroidered lace cloth, piled high with delicacies.

Date and banana bread, Sally Lunn black with fruit, frangipane tarts, spiced parkin and almond biscuits, lemon curd and fresh cream sponge, ginger and orange jumbles. And, before the ice, toasted fingers with anchovies and Leicester cheese . . .

There was a noise. One always had the illusion, she thought, that the heart of a wood was silent. Not at all. But there were noises so indigenous to their surroundings that they emphasized the silence rather than disturbing it - the movements of small animals, the rustle of leaves and, overall, the lavish ululation of birdsong. But this was an alien noise. Miss Simpson stood very still and listened.

It sounded like jerky, laboured breathing and, for a moment, she thought that a large animal had been caught in a trap, but then the breathing was punctuated by strange little cries and moans which were definitely human.

She hesitated. So dense was the foliage that it was hard to know from which direction the sounds came. They seemed to be bouncing around the encircling greenery like a ball. She stepped over a swathe of ferns and listened again. Yes - definitely in that direction. She moved forward on tiptoe as if knowing in advance that what she was about to discover should have remained forever secret.

She was very close now to the source of the disturbance. Between herself and the noise was a tight lattice of branches and leaves. She stood stock still behind this screen then, very carefully, parted two of the branches and peered through. She only just stopped a sound of horrified amazement passing her lips.

Miss Simpson was a maiden lady. Her education had in many respects been sketchy. As a child she had had a governess who turned puce and stammered all through their ‘nature’ lessons. She had touched, glancingly, on the birds and the bees and left the human condition severely alone. But Miss Simpson believed deeply that only a truly cultivated mind could offer the stimulus and consolation necessary to a long and happy life and she had, in her time, gazed unflinchingly at great works of art in Italy, France and Vienna. So she knew immediately what was happening in front of her. The tangle of naked arms and legs (there seemed in real life to be far more than four of each) were gleaming with a pearly sheen just like the glow on the limbs of Cupid and Psyche. The man had the woman’s hair knotted around his fingers and was savagely pulling back her head as he covered her shoulders and breasts with kisses. So it was that Miss Simpson saw her face first. That was shock enough. But when the woman pushed her lover away and, laughing, scrambled on top of him, well . . .

Other books

Styx (Walk Of Shame 2nd Generation #2) by Victoria Ashley

Deception by A. S. Fenichel

Pushed by Corrine Jackson

Finding Miss McFarland by Vivienne Lorret

The Ties that Bind (Kingdom) by Henry, Theresa L.

A Rogue’s Pleasure by Hope Tarr

Veiled Seduction by Alisha Rai

Kicking It by Hunter, Faith, Price, Kalayna