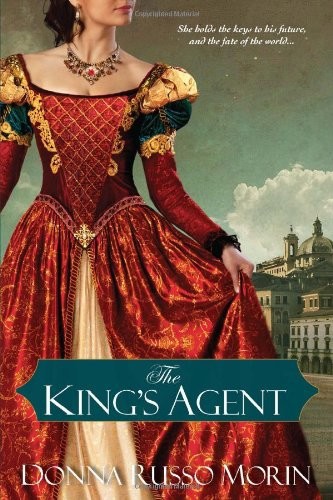

The King's Agent

B

OOKS

BY D

ONNA

R

USSO

M

ORIN

The Courtier’s Secret

The Secret of the Glass

To Serve a King

The King’s Agent

The

K

ING

’

S

A

GENT

D

ONNA

R

USSO

M

ORIN

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

B

OOKS

BY D

ONNA

R

USSO

M

ORIN

Title Page

Dedication

P

ERSONAGGI

Epigraph

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

POSTSCRIPT

ON DANTE AND THE LEGEND OF ZELDA

THE ART: WHAT EXISTS AND WHAT DOES NOT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

THE KING’S AGENT

TO SERVE A KING

Copyright Page

To Princess Zelda,

and all who love her as I do

P

ERSONAGGI

*denotes historical character

*Battista della Palla: born in Florence in 1489; served as the art agent to the French king François I.

Battista’s men:

Ascanio, antiquities expert;

Barnabeo, dealer of Battista’s excess items;

Ercole, a jack-of-all-trades, assists as needed;

Frado, Battista’s longtime companion and most trusted friend, ex-

cursion logistics manager;

Giovanni, a linguistic expert and scribe;

Lucagnolo, paintings expert;

Pompeo, once apprenticed to Cellini; inventory keeper.

*Federico II of Gonzaga: born 1500; marquess of Mantua.

Lady Aurelia: noblewoman, ward of the marquess of Mantua.

*Pope Clement VII: born 1478 as Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici; served as a cardinal from 1513 to 1523, as pope from 1523 to 1534.

*Baldassare del Milanese: an art dealer of nefarious repute; a rival of Battista della Palla.

*Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni: born 1475; sculptor, painter, architect, poet.

*Company of the Cauldron: a group of Florentine artists who gathered on a regular basis over the course of more than fifty years; the company included the likes of Giovanni Francesco Rustici, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Andrea del Sarto, and many others.

You are my master and my author,

You—the only one from whom my writing drew the noble style

For which I have been honored.

—Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Divina Commedia

One

Here one must leave behind all hesitation;

Here every cowardice must meet its death.

—Inferno

H

is hands quivered ever so slightly. Not with fear—he scoffed silently at the very notion—but with the exhilaration thrumming through his veins. His moment of triumph, of victorious possession, came upon him and he would not deny its power.

Battista della Palla stood before the carved door, shoulders hunched, broad body curled inward, as he jimmied the miniscule, well-worn silver rod into the small, square lock well. Dark eyes stole a quick, sidelong glance down each end of the empty corridor. A few flicks of his leather-cuffed wrist and ...

click

.

He hummed a contented sigh, pushed back the swath of wavy black hair from his face, and pushed over the arched swing shackle of the padlock. The heavy, intricately scrolled device dropped into his hands and he palmed it into his satchel; such locks were a treasure worth filching. For Battista, their value lay far beyond the monetary; they were trophies of a hunt well served. With a last glance to the empty passageway, a waggle of dark, thick brows, and a twitch of a smile, he took a bow to an imaginary audience and slipped in.

Stepping into the largest private room of the palazzo, he tucked his small tool back into its pouch on his cuff. One lone candle burned low in the far corner, its pale yellow light outshone by that of the three-quarter moon. The gray glow streamed through the four tall leaded windows on the opposite wall, checkering the room with squares of muted incandescence.

He had seen the inside of many a nobleman’s bedchamber, spent more than a little time in them, for here the privileged kept their valuables. Here Battista did much of his work.

The fire burned low in the grate to his left, meek blaze sparking upon the gold cloth of the pastoral tapestries covering the inside wall beside him. There, in front of him, at the foot of the curtained bed, stood the mahogany strongbox, rugged and rigid with its thick steel bands, incongruous against the flowing cerulean bed draperies.

Battista grumbled an irritated chuckle. Two more padlocks bound each band, ones equally as intricate and as valued as the first. He knelt before the large chest, knees cracking, leather braces stretching against flexing calf muscles, nettled mumblings unchecked. The duca di Carcaci guarded his treasures well.

What a shame I must steal one

.

The passing thought came and went in Battista’s mind, one tinted with pale regret, brushed away with the impatient hand of his oft-thought though transitory vacillations. He had attempted to acquire the piece through diplomatic and pecuniary methods, had offered the duke a handsome purse—more than generous—and with it offered the nobleman a chance to assist Firenze. But both opportunities had been summarily denied, and now Battista must do what he must, whatever it took for his beloved Florence. If such efforts brought him a princely income in the doing, then so be it.

He dealt with these locks—round, bulbous, and brass—as easily as the first, and tossed open the heavy cover of the chest, cringing at the grating creak of the hinges. His glance tripped up and about sheepishly, as if waiting for the door to be thrown open and incarceration to commence. But with no true cause. The stillness continued unabated, as did his thievery. Only his gaze faltered, fixed upon the massive portrait crowning the large bed.

Four people gazed back at him, their happiness in the moment and in one another captured and undeniable. The

duca,

a middle-aged man but with youthful countenance, his wife still pretty, a full figure enhanced by the attentions of a loving husband and the births of their two children. Two girls played at their feet, perhaps two years apart in age, yet identical in their dark-haired beauty and mischievous smiles.

Battista recognized his feelings of respect and longing, measured out in equal parts, for he respected a man who loved his family, as his own father had, and desired to see himself the anchor of such a portrait, the patriarch of such a family. The yearning grew with each passing year.

Not likely,

he chided himself with a surrendering shrug and a quirk of his lips,

and not now.

Florence needed him now; it could not wait while he found love or conceived children.

Battista turned his almost-black brown eyes back into the cavernous strongbox, deep-dimpled chin tucked into his chest. His face bloomed at the treasures found within, so many of them made his hand tingle as it passed over them. But he came for only one, and rummaged quietly amidst the costly rubble within until he found it.

He stood the small statuette on the palm of his hand and studied every portion of the foot-length carving. There was no mistaking the Gothic style of Nicola Pisano, nor that this piece was a model created more than two hundred years ago as a basis for one portion of the artist’s monumental work on the pulpit of the Siena Cathedral. Few knew this miniature existed, and its anonymity compounded its value tenfold. How Battista’s patron knew of it was not for him to question.

Drawing out a thick cloth from his sack, Battista efficiently wrapped the piece, and placed it vertically in the leather satchel resting on his hip—worn, smooth, and shiny, curved to his back where it had rested for years, as if it were an organic extremity born with him.

Battista closed the strongbox, reattached the locks, and—with a tip of his head in gratitude to the man in the portrait—exited the room with the same ease with which he had entered.

Quiet hugged the palazzo in its nightly embrace as Battista made his way unremarked and unnoticed to the ground floor—where Frado waited, impatiently, with their horses, just outside the kitchen door at the rear of the building as agreed—and through a statue-guarded foyer and down a west-facing corridor. It had cost Battista little to get the pretty scullery maid to explain the layout of the palazzo: a good dinner, some time in his bed—which he enjoyed as much as she, bless her feisty heart—and she’d told him of every corridor and door in the palace.

Turning left, he did little to muffle the clack of his boot heels on the ochre marble tile, or contain the strut swinging his hips. Though many locks held the treasure of the house, Battista’s thievery had been far too easily done; a man with such little a mind for security as this nobleman deserved to be robbed. Battista quickened his step as he neared the end of the corridor and the two doors on either side.