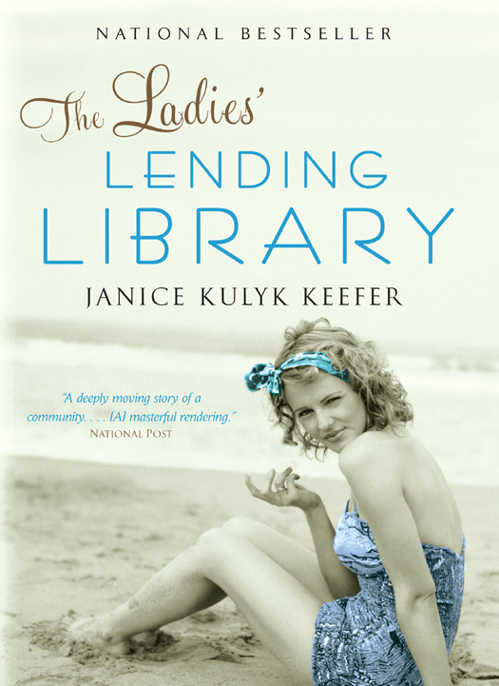

The Ladies' Lending Library

Read The Ladies' Lending Library Online

Authors: Janice Kulyk Keefer

Ladies’

Lending Library

Janice Kulyk Keefer

For Vera and Gus

T

he Ladies’ Lending Library is not an institution; though communal, it certainly isn’t public. It’s just a group of women up at the cottage for the summer, alone with their children all week and needing something to amuse them, to get them through each long and repetitious day, and to look forward to at night, in the privacy of their rooms with their half-empty beds. Something to remind them that a few things in the world are designed for people over the age of twelve—something to give them a way of feeling sophisticated and daring: women of a wider world. And so, seven of the women spending the summer at Kalyna Beach decide to pass around the books they’ve chanced upon in drugstores in the little towns on the way up to the cottage, or that they’ve smuggled in from home. Not just

The Carpetbaggers

and

The World of

Suzie Wong,

but books that Sasha Plotsky’s come across doing courses at the university:

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

and

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

But never mind the titles: the whole point is that it doesn’t matter; the books aren’t supposed to be that kind of “educational.” That’s why Sasha calls it the Ladies’ Lending Library Society; that’s why they meet for gin and gossip at Sasha’s cottage every Friday afternoon, as their husbands are starting the long drive up from the city.

There are women who would never allow themselves to be part of the Lending Library, women whose blazing virtues are a scourge to the kind of fiction making the rounds of the cottages, slipped from hand to hand, wrapped up in a beach towel or a petalled bathing cap. Women like Lesia Baziuk and Nettie Shkurka, for example. They don’t belong to anything; even their cottages are on the extreme edges of Kalyna Beach, one on the west side, one on the east. Lesia, for all her peddling of cosmetics, would go to the stake rather than read a dirty book; and as for Nettie, Sasha jokes that Nettie has vinegar in her veins and stuffs her bra with leftover Communion bread.

The Ladies’ Lending Library is not wholly an affair of gin and gossip, though the group refrains from any discussion of the literary merits of the books they read. The women talk about certain characters as though they were their dearest, oldest friends or else their fiercest enemies; often they whisper questions to one another, lying on their blankets down at the beach while their children jump across the sand.

Valley of the Dolls

is a big hit, as is

Fanny Hill, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure.

Sonia makes them laugh with this one—at first she’d refused to read it, confusing it with the

Fannie Farmer Cookbook.

It’s Sonia, too, who is most apprehensive about being a receiver of doubtful goods: she insists that

they remove the shiny jackets from the hardbacks, and make covers out of brown paper grocery bags for the paperbacks. Though, except for Nadia, all the women hide the books at the bottom of laundry hampers or in the farthest reaches of their night-table drawers. They read them late at night, when the kids are not just in bed, but asleep, and their husbands are back in the city. Not that Ivan would care if he caught his wife reading

Fanny Hill

—he’d be sitting beside her, turning the pages, Sasha jokes. But she likes the forbidden, hide-and-go-seek side of the Society, which is far more exciting, at times, than the hot parts stashed between the covers. When she is recovering from sunburn one day, Sasha sends her kids over to Sonia’s and stays in bed reading most of

Tropic of Cancer,

from which she derives sadly unfulfilled expectations regarding subway travel.

About sex, the ladies already know everything. Almost all of them married young; they had their children right away. There’s never been any time to wonder if things could have worked out differently. Sex and haste and exhaustion, sex and the fear of kids barging into the bedroom at all and any hours of the night. Never, ever, sex in the morning, sex in the afternoon. A kiss in the kitchen while you’re mashing the potatoes for supper is the warning signal for what will happen later, after you’ve done the dishes and tucked the kids in for the night, and he’s watched the hockey game or the news: not his hands, first, but the whole weight of his body sliding like a great warm seal on top of you. It takes forever, like being in a lineup at the checkout counter at the supermarket, but finally you feel the one sensation you are guaranteed: your husband’s body crumpling in your arms, for all the world like a baby that’s drunk its fill at your breast. Then he pulls away into a dead sleep, sometimes making room for you

to lie close against his chest, sometimes turning his back to you, drum-rolling into a snore.

Oh, the women have read it all, at the doctor’s or dentist’s office, in articles in

Reader’s Digest

and

Chatelaine.

How to save or add zip to their marriages—but who would go out and buy the expensive perfume, the sheer nighties (all needing to be hand-washed) like the ones they sometimes, somehow, see in cartoons from

Esquire,

not to mention the French wine and slow-burning candles the articles call for? It’s all too much like work, another version of the sessions at the washing machine or kitchen sink, and besides, the magazines never tell you what to do with the children, who are likely coming down with chicken pox or getting their fingers stuck in doors, or waking with nightmares just as you’re struggling out of your girdle into the negligee you’d have had to ask him to pay for, anyway, and of course he would have groused at the expense. And the awful, remarkable thing is this: the women aren’t really resentful, most of them; they know they’d have much more trouble surviving if they had to make room, find the time—that’s always it, the time—for any slower kind of sex than what they’re used to.

Sometimes, serendipitously, they have known moments of feeling so intense that

pleasure

seems too mild a word for it. In the pitch-black of the bedroom they bite their lips and close their eyes: if this is orgasm, they are wary of it. It happens far too rarely to be something they can count on, yet even if their husbands had the gift of pleasing them with the reliability you’d expect when switching on the burners of your kitchen stove, they would remain uneasy. The idea of physical passion—of becoming a prisoner, not to a lover so much as to your own body, its needs, its urgings—they are afraid of this. Though they’re curious, of course, as to what

happens to those who give way, as the saying goes. Bored, safely buttressed as they are, they are dying to know what happens, how and why. Which may explain why, this summer of the Lending Library, the subject they discuss most often and with the most intensity isn’t a book at all, but the new film of

Cleopatra:

the film and its aftermath, the outrageous, irresistible love affair between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. A passion they read like the most forbidden, most enticing, and thus the dirtiest book of all.

Dirty books

—this is, after all, the best, the only description that will do. Dirt is what they desire and dread in these books—no pleasure without shame, like a smudge, a soiled collar that must be scrubbed clean. For they are, above all else, respectable women: some of them may have had their lapses before marrying, but what you do in the cramped, guilty dark, you hide, and as long as nobody ever finds out, you can hold your head high. God forbid that you’ve been open, ignorant, unashamed: the way Olya had been, parading her belly for the whole world to see; marrying when Darka was five months short of being born. The way Darka gives every sign of being and doing, parading around in her two-piece like some teenaged, tinpot temptress of the Nile.

No one intends any harm to come of the Ladies’ Lending Library—no one believes any book, never mind a Hollywood movie, could do any kind of damage to the families gathered at Kalyna Beach. You could argue that what happens this summer has nothing at all to do with Sasha’s brainchild, except that the Society has added something to the atmosphere, a sense of possibility that breaks out like some contagious disease, something secret, underground, distinct from what the women think of when they hear the word

dirty.

They are all pretty incorruptible, even after reading

Fanny Hill;

that is, they remain afraid. That’s

why what happens this summer appears to them a calamity, the social equivalent, Sasha thinks, of an earthquake or a hurricane. How it came to happen they can guess at from their reading—the step-by-step science of the thing. But that it should have happened in the first place, that it should have been allowed to happen by Whoever Is Supposed to Watch Over Us—this is the mystery, and it is terrible.

Because it will end up changing everything: they will lose their innocence by gaining imagination, understanding that it can happen to any of them. That you don’t have to be Elizabeth Taylor to give way, to give yourself away. That it can happen in Hamilton as well as Hollywood. That you can make it happen.

O

lya Moya,

How I hate this place! I can’t stand the sound of the waves crashing, and the hevyness when the water is still. Water and sky and sand—there’s nothing else up here, nothing to keep me from thinking. I wish, how I wish we were girls again—things were hard then, but we could hope for anything. But we went and got married, and now there’s nothing but the ever-after. Children keep coming, days keep passing, but I’m not alive any more—my life has stopped. Oh, why did we come here at all, Olya, was it only for this? If I could wish myself back to the Old Place, the way it used to be, I’d go in a minute. I swear it. I’d leave it all behind, husband and house and even, God help me, the children. Sometimes I catch myself looking at them at the brekfast table,

seeing them at the bottom of the lake. All four of them in a row, holding hands and sitting still, so still, the waves lifting their hair, ruffling the frills of their bading suits …

Sonia Martyn is staring at the empty place on the mantel, where a small plaster statue used to stand. She looks down at what she’s just written; crumples it in her fist, but this isn’t good enough. She takes the ball of paper to the fieldstone fireplace. In her thin pyjamas measled with roses she hunkers down and lights a match. The letter flares up, quick and bright as tears, then falls into ash. She stabs it with the poker till it breaks into small, bitter flakes. In the thriller Sasha’s loaned her, a detective is able to piece together a letter that the murderer burned in a grate, picking up the charred pieces with tweezers: Sonia isn’t taking any chances.

Dear Olya,

I hope things are going well for you and Walter in the city. Everything’s fine here, no need to worry about anything. Darka’s a big help with the children and she makes herself useful with cooking and cleening, too. You’ll be happy to know she’s settled down. Of course it’s so quiet here—not much going on for a girl of her age, thank heven. Only two more weeks and the summer will be over, and we’ll bring her back to you, safe and sound.

It’s not yet six; she should go back to bed. Outside, the air is misty, as if someone’s poured cream into the sky, though the sun’s already scraping at the edges. Another fine, bright, endless day. Sonia opens the kitchen door, examining the shadfly skeletons still hooked into the screen, bleached ghosts of the insects that shed them. How, she wonders, do they crawl out so cleanly, leaving

behind this perfect trace of their bodies, even the legs, thinner than eyelashes? Do they miss their old selves, do they ever mistake their cast-off bodies for some long-lost friend, or forgotten twin? She doesn’t dare step out onto the porch: she’s afraid the hinge will squeak as it always does and waken Darka. A bad idea, giving her that poky room across from the kitchen. They would have put her in the sleep-house across the lawn, except that Sonia had promised Olya to keep both eyes on her daughter.

Olya, her best friend before their marriages: they hardly saw one another now, living as they did at opposite ends of the city, and in such different circumstances. For Olya had married Walter, a cutter at Canada Packers—had had to get married, while Sonia had bided her time until what they used to call “the right man” came along, a man with a profession, a future ahead of him. That future had turned out to contain, on his side, endless work at the office, and on hers, four children to raise. Walter Marchuk may have been as busy at the plant as Max Martyn was at his law office, but while Sonia was struggling with diapers and baby carriages and booster shots for her brood, Olya, who’d had only the one child, spent her time cleaning the houses of women who lived in suburbs similar to Sonia’s, but who had names like Brenda and Patty and Joan. For Max and Sonia had moved from downtown to a big house in a development that had been farmland ten years ago. Whereupon Olya had found excuses not to take up Sonia’s invitations to visit, and had stopped inviting the Martyns over for sloppy joes or lazy

holubtsi

at the duplex on Bathurst. It was Olya’s pride, Sonia’s mother had said; there was no forcing a friendship past the point of such pride. So now the Martyns and the Marchuks saw each other once a year, at the Martyns’ shabby cottage at Kalyna Beach, where Olya and Sonia would cook together and reminisce about

their immigrant girlhoods, pretending things were just as they’d been before husbands had hove into view, before addresses and occupations had started to matter.

Sonia had promised to take Darka for the summer, see her through a difficult patch (she was driving Olya crazy): allow her to earn some pocket money, teach her some housekeeping skills—and keep her out of harm’s way. This last part of the promise had been broken their very first night at the cottage. How could Sonia have known what Darka would get up to, disappearing into the bathroom once everyone else was in bed, experimenting with a jar of peroxide bleach she’d smuggled up in her suitcase? Max had had to buy a box of Miss Clairol (Basic Brown) so that Darka’s hair could be dyed back again, at summer’s end. Olya and Walter need never find out—but this turns Sonia into a traitor as well as a liar, as far as she can see. For this is the first summer that the Martyns have failed to invite the Marchuks up for a weekend. Darka has made it a condition of her staying on in this hole-in-the-wall at the edge of nowhere. She’s promised not to hitch a ride into Midland and from there, back to the city, on two conditions: that Sonia let her live this summer as a blonde, and that Olya and Walter be kept in the dark.

Sonia puts her hands to her face, rubbing her eyes with her fingertips. Another half-hour’s sleep might make all the difference between a good and a bad day, between drifting or dragging herself through the duties required of her, but it’s so peaceful when she’s the only one awake, the children cocooned, still, in their dreams. With the irresponsibility of a ghost she glides from room to room, watching her daughters sleep: Laura and Bonnie in the shady, sunken bedroom off the screened-in porch; Katia and Baby Alix in the sunny room across from her own. Opening

the doors so softly, imagining herself all tenderness, beautifully good, like the Blue Fairy in the movie of

Pinocchio.

They are all of them so beautiful, so good when they are fast asleep, whatever wounds they’ve got or given healing gently, as if without scars. She loves them so, she could be such a wonderful mother if only her children were always still like this, and lying sleeping.

On her night table, like a corpse waiting to be discovered, lies the paperback she’d sat up reading until two. She shoves

Death by Desire

into the drawer, to the very back, where no one will find it unless he’s looking for it. Now the night table’s all innocence, showing the nicks in the dull-white paint, paint thick like her own skin, skin of a thirty-nine-year-old woman who’s had too many children too quickly. Bare, dull-white paint with something marring the finish—a bead broken off a dress: if she were in the city right now she’d say a small, jet bead. Though, it’s not black at all, but dark red—she pushes at it with her finger, and legs spring out; it waddles off.

Sonechko.

The children have another name for it, an English name. They sing a nursery rhyme, too; she knows what the words are but not what they mean. She understands nothing of this childhood she’s given them by this miracle she’s never quite believed in—a new life in a new country. Their skipping games, the poems they learn at school, the cards they make for Christmas, birthdays—foreign territory in which she’ll never be at home. The very idea of a card for a birthday, of wasting something as precious as paper!

Flat on her stomach, face pressed into the dough of the pillow, Sonia plays at suffocation. Tonight Max will arrive with Marta and there’ll be endless rearranging. She’ll have to send Darka to the sleep-house for the week: Katia and Laura can’t be trusted together, they are always at each other’s throats. Why can’t

they get on?—if only she’d had a sister, someone to talk with, confide in, how different her life might have been. All the things she could never tell, even to Olya: hurts and shocks from the village in the lost, the long-gone country. Or the most private things, secrets crawling up and down the inside of her skin. How tonight he’ll walk in while she’s sorting dirty laundry for the next day’s wash, will plant a kiss on her neck, and she’ll stiffen; before she says a word he’ll feel her body closing up against him, and it will start all over again. He’ll tell her how exhausted he is, fighting traffic the whole way up, as if he were a front-line soldier. And she’ll answer back, without meaning it to spurt out the way it always does: “Do you think it’s any picnic for me up here, with four kids, and Darka too—I can’t take my eyes off her for a second. And now you bring me your witch of a sister. What am I supposed to do with her? I’ll go to the office and

you

stay here with her

—you

look after her and the kids all week, see how

you

like it.”

And he will, yes, how could it ever be otherwise, he’ll turn away from her in the hallway where she’s getting out the sheets to make up Marta’s bed. He’ll kiss whichever of the children are still awake, take them out on the lawn to look at the stars, not even thinking to ask if she’ll come out with them, because of course she can’t, she has a million things to do before they can all go to sleep for the night. And the children will leap to him like fish, like sunfish to a scrap of bacon, even Laura who loves no one and wallows in her own misery; the children he almost never sees and who love him all the more because of it, more than they’ll ever love her. And then, once she’s got them all into bed—which they’ll fight like little Tatars after the excitement of being out under the stars, laughing and shoving each other till Marta will call out, in her vulture’s croak, “Can’t you keep those children

under control?”—then he’ll come to bed at last, smelling of the city and the cigar he’s smoked out on the porch. For the children and the stars are only an excuse to indulge himself. He knows how she hates the stink of cigars.

He’ll undress in the dark, roll in like a driftwood log beside her, the sag in the mattress pushing their bodies together, no matter how hard she tries to keep to her side. Tonight he’ll be too tired, highway-tired, much too tired. But tomorrow, after a day spent fixing the roof or tinkering with the septic system or replacing the rotten wood on the porch steps; after getting too much sun, and putting up with the kids quarrelling over who is to hand him the nails, and who will hold the hammer when he doesn’t need it—then he’ll turn out the lights after they’ve undressed with their backs to one another; he’ll turn to her and she’ll lie there beneath him, good as gold. What else can she do, when you can hear through the skin-thin walls every sigh or cry anyone makes in their sleep?

Max wants a son. Ever since she was pregnant that first time with Laura he’s had the name picked out: his father’s name, Roman. A boy called Roman had followed her home from school all one winter, a skinny, dwarfish boy she couldn’t stand to have near her. Give him his son and he will never bother her again, that’s what it means, his turning to her each Saturday night, his body so heavy it crushes the life from her. And yet no one is a better dancer—so light on his feet, whirling her across the floor as if she were swans-down chased by a summer breeze. She sees herself and her husband like those tiny dolls placed on the top tier of wedding cakes, gliding over the stiff white icing, while all around, people are watching, envying.

Law’s such a respectable profession; he’ll go far, all the way to

Q.C.

Such a handsome man, so distinguished looking in his

tuxedo, the spotless white cummerbund, the deep red carnation in his lapel. He would always bring her a gardenia—roses were common, he used to say: she deserved something as rare as she was. A gardenia, a cummerbund—had she really married him for that? And has it really led her to this? A house in the suburbs, a tumbledown summer cottage, a body scarred with stretch marks, like silverfish crawling over her belly and across her thighs: an aging body stranded in the washed-out garden of her pyjamas.

Never mind, she has one sure consolation: her dress for the Senchenkos’ party. She has hidden it away, like the book in the night-table drawer. Sonia tiptoes to the closet, reaching into its soft depths, finding the dress

—the gown

—by the metallic feel of the fabric. She can hear her mother’s tongue clucking at the clinging folds, the low-cut neck, but as she holds the dress up against herself she is overcome by its sheer gorgeousness, the cloth dropping from her breasts like golden rain. Slippery and cool like rain, her skin drinking in the gold. If she were to step into the dress, study herself in the mirror, move in the clinging fabric as if she were on a runway and about to launch herself on a sea of unknown, admiring eyes … But she resists the lure: she makes herself shove the dress to the very back of the closet; she swears not to look at it again, to try it on, until the night of the Senchenkos’ party, lest she damage its rareness with too much looking.

Sitting on the end of the bed, facing the satin headboard (too good to be thrown out, too soiled to use at home), Sonia counts the waves beating against the shore as if they were knocks at a door she’d double-bolted. She longs for the city—not the vast, empty-seeming suburb where she lives now, but downtown where she used to work: the streetcar sparks and honking of horns, the wholesale fabric sellers on Queen, the roar of sewing machines

in the factories on Spadina. Her mother’s house on Dovercourt Road: sitting out on the porch on summer nights, people walking by, calling hello, everyone breathing in the scent of melting chocolate from the Neilson factory nearby. And it doesn’t matter how hot it gets on summer days, how steamy and drenching; in spite of the lake, in spite of Sunnyside pool, no one expects you to jump into the water.

Whereas here, if one of the children were drowning she wouldn’t be able to run in and rescue her. It’s got so bad now that she can’t go down to the water’s edge without the hairs on her arms sticking into her like pins, her fear like a rag in her mouth. Even if all four of them were to plead with her from the bottom of the lake, their arms stretched out, their mouths wide open, she wouldn’t be able to put a foot—not so much as a toe—into the lake to save them.