The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (36 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

At the level of the phrases and sentences that span many words, though, people clearly are not computing every possible tree for a sentence. We know this for two reasons. One is that many sensible ambiguities are simply never recognized. How else can we explain the ambiguous newspaper passages that escaped the notice of editors, no doubt to their horror later on? I cannot resist quoting some more:

The judge sentenced the killer to die in the electric chair for the second time.

Dr. Tackett Gives Talk on Moon

No one was injured in the blast, which was attributed to the buildup of gas by one town official.

The summary of information contains totals of the number of students broken down by sex, marital status, and age.

I once read a book jacket flap that said that the author lived with her husband, an architect and an amateur musician in Cheshire, Connecticut. For a moment I thought it was a ménage à quatre.

Not only do people fail to find some of the trees that are consistent with a sentence; sometimes they stubbornly fail to find the

only

tree that is consistent with a sentence. Take these sentences:

The horse raced past the barn fell.

The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

The cotton clothing is usually made of grows in Mississippi.

The prime number few.

Fat people eat accumulates.

The tycoon sold the offshore oil tracts for a lot of money wanted to kill JR.

Most people proceed contendedly through the sentence up to a certain point, then hit a wall and frantically look back to earlier words to try to figure out where they went wrong. Often the attempt fails and people assume that the sentences have an extra word tacked onto the end or consist of two pieces of sentence stitched together. In fact, each one is a grammatical sentence:

The horse that was walked past the fence proceeded steadily, but the horse raced past the barn fell.

The man who fishes goes into work seven days a week, but the man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

The cotton that sheets are usually made of grows in Egypt, but the cotton clothing is usually made of grows in Mississippi.

The mediocre are numerous, but the prime number few.

Carbohydrates that people eat are quickly broken down, but fat people eat accumulates.

JR Ewing had swindled one tycoon too many into buying useless properties. The tycoon sold the offshore oil tracts for a lot of money wanted to kill JR.

These are called garden path sentences, because their first words lead the listener “up the garden path” to an incorrect analysis. Garden path sentences show that people, unlike computers, do not build all possible trees as they go along; if they did, the correct tree would be among them. Rather, people mainly use a depth-first strategy, picking an analysis that seems to be working and pursuing it as long as possible; if they come across words that cannot be fitted into the tree, they backtrack and start over with a different tree. (Sometimes people can hold a second tree in mind, especially people with good memories, but the vast majority of possible trees are never entertained.) The depth-first strategy gambles that a tree that has fit the words so far will continue to fit new ones, and thereby saves memory space by keeping only that tree in mind, at the cost of having to start over if it bet on the wrong horse raced past the barn.

Garden path sentences, by the way, are one of the hallmarks of bad writing. Sentences are not laid out with clear markers at every fork, allowing the reader to stride confidently through to the end. Instead the reader repeatedly runs up against dead ends and has to wend his way back. Here are some examples I have collected from newspapers and magazines:

Delays Dog Deaf-Mute Murder Trial

British Banks Soldier On

I thought that the Vietnam war would end for at least an appreciable chunk of time this kind of reflex anticommunist hysteria.

The musicians are master mimics of the formulas they dress up with irony.

The movie is Tom Wolfe’s dreary vision of a past that never was set against a comic view of the modern hype-bound world.

That Johnny Most didn’t need to apologize to Chick Kearn, Bill King, or anyone else when it came to describing the action [Johnny Most when he was in his prime].

Family Leave Law a Landmark Not Only for Newborn’s Parents

Condom Improving Sensation to be Sold

In contrast, a great writer like Shaw can send a reader in a straight line from the first word of a sentence to the full stop, even if it is 110 words away.

A depth-first parser must use some criterion to pick one tree (or a small number) and run with it—ideally the tree most likely to be correct. One possibility is that the entirety of human intelligence is brought to bear on the problem, analyzing the sentence from the top down. According to this view, people would not bother to build any part of a tree if they could guess in advance that the meaning for that branch would not make sense in context. There has been a lot of debate among psycholinguists about whether this would be a sensible way for the human sentence parser to work. To the extent that a listener’s intelligence can actually predict a speaker’s intentions accurately, a top-down design would steer the parser toward correct sentence analyses. But the entirety of human intelligence is a lot of intelligence, and using it all at once may be too slow to allow for real-time parsing as the hurricane of words whizzes by. Jerry Fodor, quoting Hamlet, suggests that if knowledge and context had to guide sentence parsing, “the native hue of resolution would be sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.” He has suggested that the human parser is an encapsulated module that can look up information only in the mental grammar and the mental dictionary, not in the mental encyclopedia.

Ultimately the matter must be settled in the laboratory. The human parser does seem to use at least a bit of knowledge about what tends to happen in the world. In an experiment by the psychologists John Trueswell, Michael Tanenhaus, and Susan Garnsey, people bit on a bar to keep their heads perfectly still and read sentences on a computer screen while their eye movements were recorded. The sentences had potential garden paths in them. For example, read the sentence

The defendant examined by the lawyer turned out to be unreliable.

You may have been momentarily sidetracked at the word

by

, because up to that point the sentence could have been about the defendant’s examining something rather than his being examined. Indeed, the subjects’ eyes lingered on the word

by

and were likely to backtrack to reinterpret the beginning of the sentence (compared to unambiguous control sentences). But now read the following sentence:

The evidence examined by the lawyer turned out to be unreliable.

If garden paths can be avoided by common-sense knowledge, this sentence should be much easier. Evidence, unlike defendants, can’t examine anything, so the incorrect tree, in which the evidence would be examining something, is potentially avoidable. People do avoid it: the subjects’ eyes hopped through the sentence with little pausing or backtracking. Of course, the knowledge being applied is quite crude (defendants examine things; evidence doesn’t), and the tree that it calls for was fairly easy to find, compared with the dozens that a computer can find. So no one knows

how much

of a person’s general smarts can be applied to understanding sentences in real time; it is an active area of laboratory research.

Words themselves also provide some guidance. Recall that each verb makes demands of what else can go in the verb phrase (for example, you can’t just

devour

but have to

devour something;

you can’t

dine something

, you can only

dine

). The most common entry for a verb seems to pressure the mental parser to find the role players it wants. Trueswell and Tanenhaus watched their volunteers’ eyeballs as they read

The student forgot the solution was in the back of the book.

At the point of reaching

was

, the eyes lingered and then hopped back, because the people misinterpreted the sentence as being about a student forgetting the solution, period. Presumably, inside people’s heads the word

forget

was saying to the parser: “Find me an object, now!” Another sentence was

The student hoped the solution was in the back of the book.

With this one there was little problem, because the word

hope

was saying, instead, “Find me a sentence!” and a sentence was there to be found.

Words can also help by suggesting to the parser exactly which other words they tend to appear with inside a given kind of phrase. Though word-by-word transition probabilities are not enough to understand a sentence (Chapter 4), they could be helpful; a parser armed with good statistics, when deciding between two possible trees allowed by a grammar, can opt for the tree that was most likely to have been spoken. The human parser seems to be somewhat sensitive to word pair probabilities: many garden paths seem especially seductive because they contain common pairs like

cotton clothing, fat people

, and

prime number

. Whether or not the brain benefits from language statistics, computers certainly do. In laboratories at AT&T and IBM, computers have been tabulating millions of words of text from sources like the

Wall Street Journal

and Associated Press stories. Engineers are hoping that if they equip their parsers with the frequencies with which each word is used, and the frequencies with which sets of words hang around together, the parsers will resolve ambiguities sensibly.

Finally, people find their way through a sentence by favoring trees with certain shapes, a kind of mental topiary. One guideline is momentum: people like to pack new words into the current dangling phrase, instead of closing off the phrase and hopping up to add the words to a dangling phrase one branch up. This “late closure” strategy might explain why we travel the garden path in the sentence

Flip said that Squeaky will do the work yesterday.

The sentence is grammatical and sensible, but it takes a second look (or maybe even a third) to realize it. We are led astray because when we encounter the adverb

yesterday

, we try to pack it inside the currently open VP

do the work

, rather than closing off that VP and hanging the adverb upstairs, where it would go in the same phrase as

Flip said

. (Note, by the way, that our knowledge of what is plausible, like the fact that the meaning of

will

is incompatible with the meaning of

yesterday

, did not keep us from taking the garden path. This suggests that the power of general knowledge to guide sentence understanding is limited.) Here is an another example, though this time the psycholinguist responsible for it, Annie Senghas, did not contrive it as an example; one day she just blurted out, “The woman sitting next to Steven Tinker’s pants are like mine.” (Anne was pointing out that the woman sitting next to me had pants like hers.)

A second guideline is thrift: people to try to attach a phrase to a tree using as few branches as possible. This explains why we take the garden path in the sentence

Sherlock Holmes didn’t suspect the very beautiful young countess was a fraud.

It takes only one branch to attach the

countess

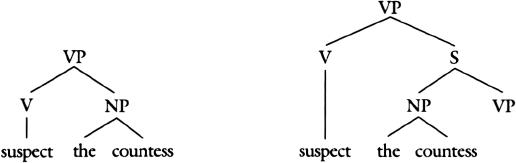

inside the VP, where Sherlock would suspect her, but two branches to attach her to an S that is itself attached to the VP, where he would suspect her of being a fraud:

The mental parser seems to go for the minimal attachment, though later in the sentence it proves to be incorrect.

Since most sentences are ambiguous, and since laws and contracts must be couched in sentences, the principles of parsing can make a big difference in people’s lives. Lawrence Solan discusses many examples in his recent book. Examine these passages, the first from an insurance contract, the second from a statute, the third from instructions to a jury:

Such insurance as is provided by this policy applies to the use of a non-owned vehicle by the named insured and any person responsible for use by the named insured provided such use is with the permission of the owner.