The Last Battle (25 page)

Authors: Stephen Harding

As he crossed the terrace, Lee was pleased to see that Gangl had placed two of his men behind a low wall that allowed them to cover both the castle’s

main entryway and the stairway leading up from the front courtyard. The soldiers saluted the American officer as he walked past them into the Great Hall, where Lee found Gangl and Schrader waiting for him. Together, the three men set off to inspect the defenses. Then it was down to the cellars to look in on the VIPs and Schrader’s family, followed by a drawn-out strategy session among Lee, Gangl, and Schrader that evolved into a remarkably open discussion of the war and the uncertainties of the coming peace. It must have been a truly odd sight: the brash tanker from upstate New York and two highly decorated German officers, sitting around a table in the candlelit great hall of a medieval castle, speaking quietly of their experiences in a conflict that each man fervently hoped would end within hours.

Finally, talked out, the enemies-turned-allies went in search of places to catch a few hours’ sleep. Lee ended up in what had until recently been the SS guards’ dormitory on the first floor of the keep. Setting his helmet and M3 submachine gun on a bedside table, he picked one of the narrow beds at random and lay down on the bare mattress still wearing his boots and pistol belt. His foresight would soon be validated, for it would be a very short night.

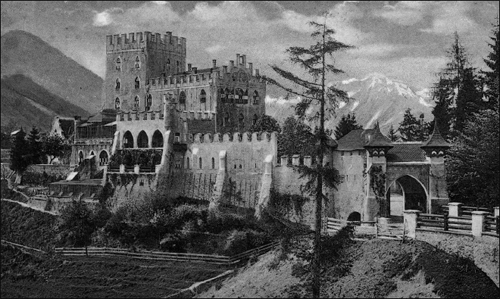

Sited atop a hill that commands the entrance to Austria’s Brixental Valley, Schloss Itter is first mentioned in the historical record in 1241. Damaged, rebuilt, and enlarged over the centuries, before its 1941 conversion into a VIP prison it had served successively as a military fortress, a private home, and a boutique hotel.

(Author’s collection)

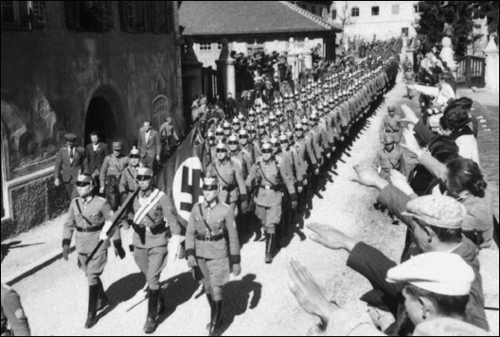

German police march into Tyrol following Germany’s March 12, 1938, annexation of Austria. The Anschluss led directly to Schloss Itter’s transformation from fairytale castle and hotel into something decidedly more sinister.

(National Archives)

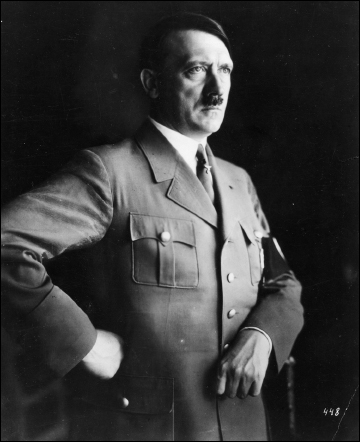

The network of “special prisons” maintained by the Nazis grew from Adolf Hitler’s belief that important prisoners might prove of value in negotiations with the Allies.

Ehrenhäftlinge

—honor prisoners—were housed in reasonably good conditions in castles, hotels, and similar facilities throughout the Reich, though their continued good health relied solely on the führer’s whim.

(National Archives)

Though Hitler fully supported the work of the Schloss Itter–based “Alliance for Combating the Dangers of Tobacco,” Reichsführer der SS Heinrich Himmler believed the Austrian castle was ideal for more nefarious purposes. On November 23, 1942, he got Hitler to sign an order to begin the process of acquiring the castle outright for “special SS use,” and Schloss Itter was officially requisitioned by the SS in February 1943.

(National Archives)

SS Major General Theodor Eicke, the director of the Nazis’ concentration camp system and originator of the “inflexible harshness” doctrine applied to KZ prisoners, directed that Sebastian Wimmer and the commanders of other honor prisoners’ facilities treat their prisoners well but stand ready to execute the VIPs at a moment’s notice, without compunction and without remorse.

(National Archives)

Plans for Schloss Itter’s conversion from an antismoking administrative center into a high-security honor prisoner facility were apparently overseen by no less a personage than Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister of armaments and war production.

(National Archives)

By the time he arrived at Schloss Itter, General Maurice Gamelin had spent more than fifty of his seventy-one years as an officer in his nation’s army. His career was marred, however, when his poor response to Germany’s May 1940 invasion of France led Prime Minster Paul Reynaud to replace him as supreme military commander with archrival General Maxime Weygand.

(National Archives)

Stocky, barrel-chested, and pugnacious, sixty-one-year-old Édouard Daladier was the youngest of the three VIPs whose arrival at Schloss Itter on May 2, 1943, marked the castle’s official opening as a prison.

(National Archives)

Seen here during a prewar visit to the United States, labor leader Léon Jouhaux and his colleague and longtime companion Augusta Bruchlen both ended up imprisoned in Schloss Itter; Bruchlen’s incarceration in the Tyrolean fortress was voluntary, Jouhaux’s was not.

(National Archives)