The Last Speakers (12 page)

Authors: K. David Harrison

Kafote, the young, dynamic leader of the community, sat down to talk to us about the future of his culture. What changes had he witnessed over the past 20 years? He turned immediately to the topic of the traditional religion: “The culture is weak now. Twenty years ago shamans were still curing; the culture was strong. Veneto is the last strong shaman with powers. He cures by biting the patient and drawing out the sickness in his hand, shows it to the people, then gets rid of it.”

Though not a shaman himself, Kafote described different types of shamans: There are “big fish, rain, earth, and forest [shamans]. Some are more powerful than others. Some shamans live on earth and others live underground or in the sky. To be a shaman, one must dream of the invisible gods. When the shaman sleeps, he goes up to the god's world and obtains their powers. There are different types of gods and powers. When the shaman dreams and sings, the gods give him more power. The most powerful shaman lives in the area of Puerto Leda. We cannot talk to him because he is a god, and invisible.”

Turning to the issue of subsistence, Kafote asked, “Why do we have to eat noodles now? Because we no longer have gods who help us. We have to work to get some kind of money and buy something. But before, the gods gave it all. You just had to sing, for example, to call a fish, and the fish would fall before you. Before, you could sing and call for the wild pigs, and they would come and we ate them. Now it's more difficult.”

Thinking of all the fishermen we had seen on the river, we wondered if they still used songs to call fish, if they still practiced the religious rituals to ensure bounty. “Yes, people still use them, but we cannot get into Puerto Leda and visit the most powerful god, who would give power to our people. It is now prohibited to go on the land that was once ours. The government sold it to the Moonies. Now we can only work, so our way of life is degrading. In 20 more years, we will no longer have anything.”

Concluding the interview, we asked Kafote what he would like the world to know about his people. Looking directly into the camera, he began an impassioned and tearful speech: “Our lands are so small,” he began to weep as he said it, “

muy pequeñas,

and we are crowded in from all sides, with people taking our forests and poisoning our rivers. We have mercury in the fish, and a dry well in the village. We get nothing from the logging and mineral extracting companies. The toxins they use seep into our river and contaminate our water. We want to buy back some of our traditional lands, where there are still animals, but it's too expensive now.”

LANGUAGES OF A SECRET LAND

The indigenous people of Paraguay remain a secret within an enigma. Many live in the inhospitable backcountry, the Chaco, accessible only by air, boat, or seasonally impassable dirt roads. In Asunción, the modern capital city, people expressed surprise at our destination: “There are languages out in the Chaco?”

While poor in some respects, Paraguay is indeed rich in languages, forming part of the central South America language hotspot. In addition to Spanish, Paraguayan peoples speak at least 18 languages, grouped into 6 distinct language families. To calculate the linguistic diversity index for Paraguay, we divide the number of families (6) by the number of languages (18), yielding an index of .33. This astonishing level of diversity triples that of Europe, which, with its 18 language families and around 164 languages, yields a diversity index of just .11. How did so many languages evolve in such a remote place, and among such a small (less than 200,000 total) population? Part of the answer lies in geography. The Chaco is burning hot and dust-filled in the summer, besieged by mosquitoes and impassible in the wet season, and filled with thorny plants and poisonous snakes. It defies even the barest level of subsistence living. And yet these small tribes have managed to thrive here.

Survival dictated mobility. No one place could support people year-round, and so the Chaco peoples fished at the riverbank for half the year, then trekked into the dry interior to forage for the other half. Conditions forced local tribes to continually fissure into smaller groups that could support themselves off the land and prevented the consolidation of peoples into larger settlements. Despite the ferocity of the land, richly imaginative cultures sprang up here, with fantastic mythologies, feather-dancing rituals, and discoveries about the medicinal uses of local plants. What remains of this knowledge in these survivor cultures?

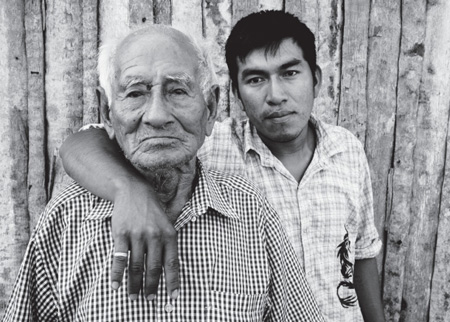

Elders still alive today, like Baaso, who gave his age as 100, recall the precontact era. Baaso recounted to us how, during his early years, his peopleâthe Ishirâwore no clothing besides animal skins, had no knowledge of metal, glass, or guns, and had no source of nutrition besides the fish they caught, small animals they shot with bow and arrow, and berries and honey they foraged from the forest. Dividing their time between temporary encampments along the river and foraging sites in the dry interior, Baaso's people had not at that time seen outsiders, airplanes, or any other modern technology. Once contact happened, the world came crashing in on the Chamacoco, and they were exposed to warfare, weapons, subjugation, and sedentarization. In Baaso's own centenarian lifetime, we can trace the arc of an isolated, precontact people from living as hunter-gatherers in a stone-age subsistence pattern to living in villages in sight of a mobile phone tower and an airstrip, granting interviews to visiting scientists, and sending out their stories and reminiscences to a global audience over the Internet.

Baaso's grandson, Alvin Paja, listened with a bemused expression as his grandfather talked about hunting with bow and arrow. Alvin likes to fish, but he uses motorboats and is conversant in text messaging and the latest Argentine telenovelas. He can only imagine the world his grandfather inhabited, and yet he is connected to it through the stories, the words, and the Chamacoco language.

Baaso, with grandson Alvin at his side, related all this with a sly sense of humor and a desire to tell his own story. He may have been pulling our leg just a bit, since an elder in another village insisted that Baaso was not 100, but only 85. Either way, his mind was clear, and his experiences, both pre-and postcontact, rang true. They are the Ishir people's collective fate. Having been plunged from the deep past into the dizzying present, fast-forwarding centuries of technology in the span of a single lifetime, Baaso's perspective is utterly unique and remarkable.

Baaso, a Chamacoco elder, with his grandson, Alvin Paja Balbuena, in Puerto Diana, Paraguay.

Across the village from Baaso's place, elder Agna Peralta, wearing a bright red dress, took out her dried gourd rattle, stood purposefully in front of her house, and burst into song. The deep overtones coming from her small and seemingly frail body took us by surprise, a loud and potent mix of chant, rhythm, and incantation. The rhythm of the gourd shaker slowed down, then picked up speed again:

“Ekewo dashiyo lato ehuwoâ¦.”

I jotted down syllables in my notebook, making a rough transcription but not comprehending. Agna later told us the lyrics were repeated variations on “Come, fish, come to my house.” She learned this song from her father, a shaman, and its purpose was to beckon the river creatures to provide sustenance.

No fish were summoned by Agna's powerful voice on this occasion, but children from all over the village made a beeline to her house. They looked in bewilderment at us, the National Geographic team with our cameras, recording devices, and notebooks, as we sat listening with rapt attention to Agna's song. The song itself was a rare occurrence, and the fact that a team of scientists had come from afar to hear it sung made quite an impression. I wondered if the children were paying attention to the lyrics, in a language they are increasingly filtering out in favor of Spanish. At last, Agna stopped singing and set down her rattle. “Maybe tomorrow I can sing again,” she told us. “Now, I'm tired.”

At the nearby school, a brother and sister aged eight and ten said, yes, of course, they still know songs in Chamacoco, and they dutifully sang a song at the prompting of their teacher, Señora Teresa. Though we saw joy in their faces, it seemed very much like an effort and a performance. Clearly they were more comfortable chatting among themselves in Spanish, and this schoolyard habit may have already determined the future fate of Chamacoco, at least in Puerto Diana. Señora Teresa said the children knew some Chamacoco, but it was “a language at risk of extinction.” She showed us a first-grade textbook in the language, compiled by her and her fellow teachers. She asked her student, eight-year-old Pedro, to read from the book. Haltingly, he attempted to sound out the syllables. Señora Teresa corrected him and then translated for us into Spanish, from what sounded like a primer for cultural assimilation: “Here we are in the white people's school. They are teaching how to eat.” “Eating on the ground is unclean.” “On our desks we will do beautiful things.”

16

Departing Puerto Diana, we set off downstream in a couple of rickety canoes to visit one of the very smallest villages in all of Paraguay, tiny Karcha Bahlut, which in the Chamacoco tongue means “Big Shell, Little Shell.” Fewer than 100 souls, plus a few itinerant fishermen, perch on a high escarpment that overlooks the river. The precipice is a midden composed of millions and millions of shells. Some archaeologists assume these were deposited by humans and are thus a sign of ancient habitation. An opposing view was explained to us by Jota Escobar, Paraguay's leading ornithologist, who thinks the shells were deposited by birds, and that humans happened along later to partake in the feast and add to the pile. Either way, the shell midden is massive and solid. Atop it stand rickety huts with hammocks and small fenced enclosures for pigs.

With some frustration, I shook my GPS, restarted it, and moved it to another spot so it could detect the satellites. It was hard to believe, but we appeared to be in a satellite black hole and could not get a fix on the location of the Chamacoco villages. I later confirmed with cartographers at National Geographic that there are indeed gaps in GPS satellite coverage, with its bias toward the Northern Hemisphere. The Chamacoco people exist in one of those gaps. Their lands can, however, be viewed from Google Earth or an airplane, where a sobering picture of rampant deforestation and river pollution emerges.

The only solid building in Karcha Bahlut is a brick school, said by locals to have been built by “Los Moons” (the Moonies) who originally came to proselytize but then left suddenly, apparently with no converts, leaving behind the gift of a schoolhouse. In it, we found young, energetic Alejo Barras shepherding his first-and second-grade students. As we watched the lesson, we realized how utterly foreign Spanish is to these kids. Just a few miles down-river from Puerto Diana, where the Chamacoco children chatter in Spanish all day, these village children laboriously repeated a few basic words:

casa, trabajo, mano

. It was a real joy to see that these children are basically monolingual speakers of Chamacoco, but their situation is unique and does not mirror that of most children in the other Chamacoco villages. They inhabit a linguistic island, the last and smallest place in all the once-vast traditional Chamacoco territory where Spanish has not totally dominated.

Inspired by Alejo's efforts, we asked what we could do to help out. Lacking a single clock or watch in the village, he said he had trouble rallying the children to school on time. I quickly took off my digital watch and handed it over to him. The value to me of a $100 sports watch was nothing compared to its value in this village. Then Alejo showed us an alphabet book designed to teach basic literacy in the Chamacoco language. It contained pages devoted to each letter and to objects that could be spelled with it. “We only have a few copies,” he said. “Can you help us make more?” In moments, we set the textbook out on the ground in a sunny spot and carefully photographed each page. We would take these images back to Asunción and mass-produce a hundred textbooks for this village and for the school in Puerto Diana. This small gesture on our part, costing only a few thousand guaranis, could truly tip the balance in the effort to keep Chamacoco alive.

Fortunately, the Ishir do not lack for young, charismatic leaders, and we found such a person in Kafote. His Spanish name is CrÃspulo MartÃnezâlike all Ishir, he gave his Spanish names first to outsiders, but his Ishir name remains his true, if somewhat secret, designation. Kafote represents the struggle of his people, as they cope with mercury poisoning in their river, clear-cutting of trees by Brazilian loggers, and cultural assaults by missionaries of all stripes. Their defense strategy is as simple as their basic needs: keep the land, fight for clean water and against deforestation, keep the culture, keep the language.

In so many ways, Paraguay remains off the map, an enigma. Guidebooks to South America give it the least coverage of any country, and it enjoys little tourism. It suffered for decades under a dictatorship that left it underdeveloped. Though Asunción is now a vibrant city, European in its tastes, the country as a whole remains largely unknown by outsiders. Perhaps it is meant to be kept secret. A local sculptor told us, “Thanks for coming to Paraguayâ¦but don't tell anyone!” Most Paraguayan indigenous languages are quite poorly known and only minimally described in grammars, and those grammars are often produced in very small print runs and unavailable to scholars.