The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (14 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Several “mammoth hostelries” were being planned for the city, including one to be built by a syndicate headed by the owner of Toronto’s famous Queen’s. It would be “the most complete hotel building in the West outside of Chicago,” but this was cold comfort to those who tumbled off the cramped trains into the snow without a hope of accommodation. During one fearful blizzard in early March, when the wind reached hurricane force and it was impossible to see half a dozen yards in any direction, several immigrant parties had to be lodged temporarily in the

CPR’S

passenger depot. During that month the National Manufacturing Company of Ottawa rushed fifteen hundred heavy cotton tents to Winnipeg. On the outskirts of town giant tent boarding houses began to rise in rows. These

gargantuan marquees were large enough to accommodate within their folds a cluster of smaller tents, each capable of sleeping eight men. By May, the ever-alert Arthur Wellington Ross was importing portable houses from an eastern manufacturer. Space was at such a premium that he was able to rent them all before they arrived.

That social phenomenon, the Winnipeg boarding house, had its birth that year. It was unique – “a style to be found nowhere else in the Dominion,” in the words of a man who endured one. Architecturally it was a hybrid – half tent, half ramshackle frame. Entirely unpartitioned, it served as a combined dormitory, dining room, scullery, and smoker.

“You open the door and immediately there is a rush of tobacco smoke and steam mingled with indescribable results which makes you want to get outside and get a gulp of fresh air. You go to the counter and get tickets from the man behind the desk for supper, bed and breakfast. There are no women about and no children. Nor are there any elderly people – they are all young men. You have no time to study them for through the mist of smoke in the great room there breaks the jangling call of a bell and a terrible panic seizes the crowd. It is not an alarm or fire nor is there any danger of the building caving in, neither is it a fight nor a murder – it is only supper.”

Supper consisted of a plate of odorous hash, flanked by a mug of tea and a slab of black bread, served up by a number of “ghastly, greasy and bearded waiters with their arms bare to their elbows and their shirt bosoms open displaying considerably hairy breast.” The meal was devoured in total silence, the only sound being “a prodigious noise of fast-moving jaws, knives, forks and spoons.”

The boarders themselves were a motley lot: “Men who were at one time high up in society, depraved lawyers, and decayed clergymen brought down by misconduct and debauchery, but still bearing about them an air of refinement … carpenters smelling strongly of shavings, mill hands smelling of sawdust and oil, teamsters smelling of horse, plasterers fragrant with lime, roofers odorous with tar, railway laborers smelling of whiskey, in short all sorts and conditions of men.”

At night, when the tables were cleared and the occasional drunk subdued with a club, a man at the end of the building picked up a ladder, planted it against the wall, and told the inmates to clamber into their bunks among the grey horse-blankets that served as bedding.

For such accommodation, new arrivals were happy to pay double the rates at better-appointed eastern hotels. “The cost of living is something incredible,” the

Globe

informed its readers. “Housekeeping here must be

done with the most rigid economy or it is ruinous.” Wages were the highest in the land. Day labourers got as much as three dollars a day, triple the Ontario rate. Carpenters were paid up to four dollars a day, plasterers seven dollars, masons eight dollars. As one immigrant wrote back home, however, since there was such a shortage of accommodation “mechanics are spending what they earn in trying to live.” A single cramped room cost as much as twenty-five dollars a month. (The Toronto price was five dollars.) Frozen potatoes were two dollars a bushel, eggs forty-five cents a dozen, beefsteak thirty-five cents a pound, and milk – sold in the winter in frozen blocks – ten cents a quart.

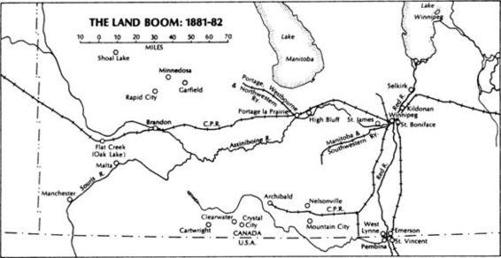

Still the immigrants poured in. Often their enthusiasm was dampened when they reached the city. One carpenter, arriving in March, found he could get no work because his employer had no shop. Moreover, the station platform was covered with tool boxes and he realized that his fellow artisans, arriving by the score, would make his services a drug on the market. In St. Paul that same week, an unnamed Canadian uttered one of the few murmurs of gloom voiced about the prospects in Manitoba. “When the tumble comes in Winnipeg it’s going to be something awful,” he said. But among the swirling crowds in the auction rooms of Main Street, bidding higher and higher for lots in towns and “cities” like Emerson, Shoal Lake, West Lynne, and Minnedosa, there was still no hint of the reckoning to come.

3

“Towns cannot live of themselves”

The Winnipeg land boom can be divided into two parts. The boom of 1881 was followed by a lull in late January and February before the spring boom of 1882 began. The weather in mid-February was as fickle as the market, being warm and sunny one day, chill and gusty the next. On February 16, the city fell under the lash of one of the worst storms it had yet known, a truly blinding blizzard, which cut through the thickest clothing and brought all movement to a stop. Speculators who had come into town from outlying points found themselves imprisoned by the cold. Even the

CPR

trains were unable to travel west to Portage la Prairie and Brandon; although the track had been built high and ditched carefully to prevent just such a calamity, the roadbed was effectively blocked by a wall of packed snow.

February, it was said, would test the stability of the boom. At first, the storm seemed to act as a depressant; the demand for city property ebbed.

Undismayed, the entrepreneurs began to boost other Manitoba “cities” to the point where those who held property on Winnipeg’s outskirts tried to sell out in order to take advantage of more attractive bargains. In most cases they found they could not sell. The boom had moved on to Mountain City, Selkirk, and a score of unfamiliar communities where, it was whispered, new railroads would soon be built.

As a result, extraordinary efforts had to be made to sell outlying lots in the immediate Winnipeg area. Curiously, the prices of these lots did not go down; rather they rose. Properties many miles from the centre of town, which could have been purchased the previous fall for fifty dollars an acre, carried, in late February, price tags ranging from two hundred and fifty to one thousand dollars.

The asking prices were so high, in fact, that it was doubtful whether any purchaser would be able to make more than the downpayment. This, apparently, did not matter. Real estate speculation in Winnipeg that spring resembled very much the dime chain-letter crazes and the pyramid clubs of a later era. Everybody reasoned that the real profits would be made by those who moved in early and got out swiftly; every man expected that somebody would eventually be left holding the bag; but no one was so pessimistic as to believe that he would be caught with worthless property.

The sellers had so little confidence that the prices would be maintained that they tried to get the largest possible downpayment and the shortest terms. The new purchasers, in turn, arranged at once with a broker to have their interest transferred to a syndicate at a handsome advance on first purchase consideration. The syndicates, in their turn, hired groups of smart young men to extoll the virtues of the property as “the best thing on the market.”

Because it was difficult to move properties that could not be shown on the latest map of Winnipeg and its environs, the land sharks resorted to subterfuge. Maps were cut and pasted so that outer properties seemed to be much closer to town than they really were. In late February, lots 25 by 110 feet in size more than three miles southwest of the Assiniboine, far out on the bald prairie, were selling for fifty dollars each. It was several decades before the city extended that far.

On Main Street, Winnipeg’s lung, where Red River carts in staggered line had once squeaked through the mud twelve abreast (thus ensuring that it would become the widest street in Canada), the prices continued to climb. At the corner of Main and Thistle, a lot with a frontage of eighteen feet on which the Cable Hotel was situated sold for thirty-five thousand dollars or $1,944 a front foot. But the real action was taking place in the smaller communities of Manitoba.

The safest investments were to be found at Brandon and Portage la Prairie, for these were established centres on the main line of the

CPR

. The boom in Brandon had not abated since the summer of 1881. “Nobody who saw Brandon in its infancy ever forgot the spectacle,” Beecham Trotter wrote. Trotter nostalgically recalled a variety of sights and sounds: the hillside littered with tents, the symphony of scraping violins playing “Home, Sweet Home” and “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” the cries of the auctioneers: “All wool from Paisley; and who the hell would go naked?” Brandon lots were still rising in price. Early in January a syndicate which included Alexander Morris, a prominent Conservative and a former lieutenant-governor of Manitoba, had been formed especially for the purpose of buying the remainder of the townsite from the

CPR

; the price was a quarter of a million dollars. (The railway promised, in return, to locate its workshops in Brandon.) The demand for these lots when they went on the market in Winnipeg was acute enough to force the Queen’s Real Estate Exchange to close its doors after seven in the evening to all save those who wanted to deal in Brandon property. So all-embracing was the real estate fever in Brandon that when the town was laid out no provision was made for a cemetery. The dead had to be brought to Winnipeg for burial.

Portage la Prairie, advertised in March as the “Greatest Bargain of this Spring Boom!” was in a perfect frenzy of speculation. “A craze seemed to have come over the mass of the people,” an early chronicler recounted. “Legitimate business in many cases was thrown aside, and buying and selling lots became the one aim and object of life.… Carpenters, painters, tailors, and tradesmen of all kinds threw their tools aside to open real estate offices, loaf around the hotels, drink whiskey and smoke cigars. Boys with down on their lips not as long as their teeth would talk glibly of lots fronting here and there, worth from $1,000 to $1,500 per lot.”

The Portage, at that time, had a population well below four thousand. Of the 148 business institutions, forty-one were real estate offices, operated by every kind of human specimen from former cowboys to ex-priests; three more were banks loaning money to speculators, five others were loan and investment companies backed by eastern capital, and another nine were jobbing houses acting as agents for private capitalists.

“Men who were never worth a dollar in their lives before, nor never have been since, would unite together, and, on the strength of some lots, on which they had made a small deposit, endorse each other’s paper, and draw from the banks sums which they had never seen before, only in visions of the night.”

The Portage boom was at least understandable, since the town was a prominent station on the main line of the railway. The Rapid City boom was more mysterious. It may have been, as some suggested, that the very name of the community caught the imagination of the speculators. Certainly it remained a favourite for months, at times running a close race with Winnipeg itself. It was surely one of the most remarkable paper communities in the province: although its population was well under four hundred, the city was laid out with intersecting streets for eight square miles.

The fever persisted in the face of the obvious fact that the

CPR

had passed Rapid City by. In 1879, when it had been established by a private syndicate, Sandford Fleming’s survey gave every indication that the

CPR

would pass that way. The decision to move the line south through Brandon ought to have destroyed its hopes but, such was the optimism of those times, the belief persisted that Rapid City would shortly become a great railway centre. “The flow of immigration into and through this town is unprecedented in the history of the settlement of this country,” one resident informed the Winnipeg

Times

in early April. The road between Brandon and Rapid City was lined with wagons loaded with speculators, settlers’ merchandise and effects, and with horses, cattle and sheep. Every hotel and every stable in town was overcrowded. Vacant land was being snatched up so swiftly that two or three men would sometimes arrive at the land office within minutes of one another, each intent upon grabbing the same section.

As late as May 30, a Rapid City doctor reported that “Rapid Cityites are not at all despondent over the change of route of the

CPR

but confidently

expect having a railway connection with some place or other before twelve months – even if the people have to build the line themselves.” Advertisements in the Winnipeg papers actually boasted that

six

railways would soon run through the community.