The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (34 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

1

Onderdonk’s lambs

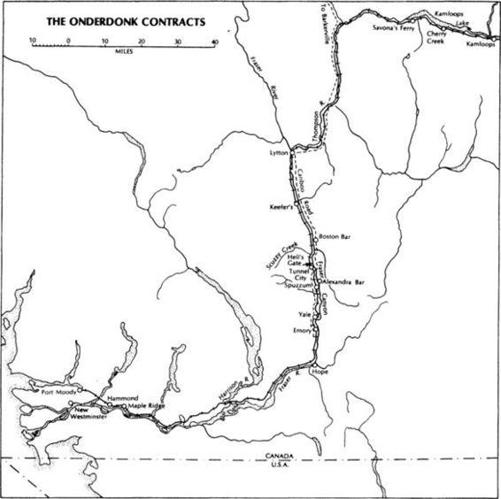

Almost every leading figure connected with the building of the great railway – with one notable exception – achieved the immortality of a place name. The map of western Canada is, indeed, a kind of coded history of the construction period. The stations along the way (some of them now abandoned) tell the story of the times: Langevin, Tilley, Chapleau and Cartier, Stephen and Donald, Langdon and Shepard, Secretan, Moberly, Schreiber, Crowfoot, Fleming, and Lacombe. Lord Dunmore, who tried and failed to secure the original contract, has his name so enshrined along with Lord Revelstoke, who came to the company’s rescue by underwriting a bond issue. Harry Abbott, the general superintendent, has a street named after him in Vancouver, along with Henry Cambie, the surveyor, and Lauchlan Hamilton, who laid out most of the

CPR

towns; Thomas Shaughnessy has an entire subdivision. Macoun, Sifton, and even Baron Pascoe du P. Grenfell, one of the more obscure – and reluctant – members of the original syndicate, are recognized in stations along the main line. Rosser and Dewdney are immortalized in the names of the main streets in the towns they founded. Most of the leading figures in the railway’s story had mountain peaks named after them; Van Horne, indeed, had an entire range. But the connoisseur of place names will search in vain on mountain, village, park, avenue, subdivision, plaque, or swamp for any reference to the man who built the railway between Eagle Pass and Port Moody through some of the most difficult country in the world. There is not so much as an alleyway named for Andrew Onderdonk.

Perhaps he would have wanted it that way, for he was a remarkably reticent man. He did not inspire the kind of anecdote that became part of the legends of Van Horne, Rogers, and Hill. No biographer appeared before or after his death to chronicle his accomplishments, which included the San Francisco sea-wall, parts of the Trent Valley Canal, and the first subway tunnels under New York’s East River. In the personal memoirs of the day he remains an aloof and shadowy figure, respected but not really known. Rogers, Hill, and Van Horne were each referred to by their underlings, with a mixture of awe, respect, and terror, as “the old man.” Onderdonk was known to everybody, from the most obscure navvy to the top engineers and section bosses, by the more austere title of “A.O.”

If those initials had a Wall Street ring, it was perhaps because Onderdonk looked and acted more like a broker than a contractor. In muddy Yale, which he made his headquarters while his crews were blasting their

way through the diamond-hard rock of the Fraser Canyon, he dressed exactly as he would have on the streets of his native New York. He took considerable care about his personal appearance. His full moustache was neatly trimmed and his beard, when he grew one, was carefully parted in the middle, as was his curly brown hair. He was tall, strapping, and handsome, with a straight nose, a high forehead, and clear eyes – an impeccable man with an impeccable reputation. “Onderdonk,” recalled Bill Evans, a pioneer

CPR

engineer, “was a gentleman, always neat, well dressed and courteous.” When he passed down the line, the white workers along the way – Onderdonk’s lambs, they were called – were moved to touch their caps. A woman in Victoria who knew him socially described him as very steady and clear headed, but added that he did not have much polish. In that English colonial environment, where tea at four was as much a ritual as an Anglican communion, few Americans were thought to be polished. But to the men sweating along the black canyon of the Fraser, Andrew Onderdonk must have seemed very polished indeed. Henry Cambie, the former government engineer who went to work for him, described him, as many did, as “a very unassuming man” and added that he was both clever and a good organizer and was “possessed of a great deal of tact.” In short, Onderdonk had no observable eccentricities unless one counts the monumental reticence that made him a kingdom unto himself and gave him an air of mystery, even among those who were closest to him.

But no one was really close to him. If any knew his inner feelings, they left no record of it. If he suffered moments of despair – and it is clear that he did – he forbore to parade them before the world or even before his cronies. It was not that he shunned company; the big, two-storey, cedar home, with its gabled roof and broad verandahs, which he built in Yale to house his wife and four children, was a kind of social centre – almost an institution, which, indeed, it later became. Onderdonk was forever entertaining and clearly liked to play the host. “We lived as if we were in New York,” Daniel McNeil Parker, Sir Charles Tupper’s doctor and friend, wrote of his visit there with the minister in 1881. The contractor and his wife were described by a friend as “a happy-go-lucky couple … fond of enjoying themselves.” Cambie, in his diaries, notes time and again that he dined at the Onderdonks’. But Cambie, who had a good sense of anecdote, never seems to have penetrated that wall of reserve.

Onderdonk’s modesty was matched by that of his wife Delia, a short, plump and pretty blonde, who was “the most modestly dressed woman in Yale,” a frontier town where all the engineers’ wives, having precious little else to occupy them, vied with each other in the ostentation of their

frocks and gowns. “A nice, unaffected American lady,” Dr. Parker wrote of her.

If Onderdonk presented a cool face to the world, it was partly because he did not need to prove himself over and over again. He had been raised in security; in his daughter’s words, “his family on both sides were gentle people of education.” Onderdonk differed from most of the contractors of his time and from all the other major figures in the story of the railway. Each one of them – Donald A. Smith, Duncan McIntyre, John S. Kennedy, Norman Kittson, James J. Hill, George Stephen, Sandford Fleming, and William Van Horne, right on down to Michael Haney and A. B. Rogers – had been a poor boy who made it to the top on his own. Most were either immigrants or the sons of immigrants; but Onderdonk came from an old New York family that had been in America for more than two centuries. He was a direct descendant of Adrian van der Donk, a Dutchman who sailed up the Hudson in 1672. His mother was pure English – a Trask from Boston. Fourteen members of his immediate family had degrees from Columbia. His ancestral background was studded with bishops, doctors, and diplomats. Onderdonk himself was a man of education with an engineering degree from the Troy Institute of Technology. He did not need to swear loudly, smoke oversize cigars, act flamboyantly, or throw his weight around. It was not in his nature to show off; he was secure within himself, a quiet aristocrat, “very popular in local society circles,” as the Victoria

British Colonist

put it.

Onderdonk’s sense of security was also sustained by the knowledge that he had almost unlimited funds behind him. He was front man for a syndicate that included H. B. Laidlaw, the New York banker, Levi P. Morton of Morton, Bliss and Company, a prominent eastern banking house, S. G. Reed, the immensely powerful vice-president of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, and last, but by no means least, Darius O. Mills, the legendary San Francisco banker.

Mills handled the financial end of the Onderdonk syndicate. He was everything that Onderdonk was not, having clawed his way to his position as one of the boldest and most astute financiers in America by striking it rich in California in 1849 – not by finding gold but by chartering a sailing vessel, loading it with all the commodities likely to be in short supply in the California camps, and sailing it successfully around the Horn. Mills sold out his stock to the eager miners at fabulous prices and went on swiftly to fame and fortune, becoming the first president of the Bank of California and marrying off his daughter to Whitelaw Reid, proprietor of the New York

Tribune

.

In 1880, when he and Onderdonk were securing their first contracts in British Columbia from the Canadian government, everybody was talking about Mills’s palatial office building being planned on Broad Street, New York (the finest in the world, it was said: thirteen structures had to be demolished to accommodate it), and his even more palatial private home opposite St. Patrick’s Cathedral, “a mansion of which a Shah of Persia might be proud,” for which, it was reported, he had paid the highest frontage price in history. The carved woodwork, painted ceilings, inlaid walls and floors cost him an additional four hundred and fifty thousand dollars. As for his office building, it was garish with Corinthian pillars, red Kentucky marble, and Italian terracotta. No wonder the Canadian government was intrigued when it learned who was bankrolling Andrew Onderdonk.

Charles Tupper, the Minister of Railways, had had his fill of underfinanced contractors, some of whom had been forced to give up on the Thunder Bay-Red River line, to the embarrassment of the government. Although Onderdonk’s tenders for the four British Columbia contracts were by no means the lowest, he managed with Tupper’s help to buy them all up from the successful low bidders. It was agreed that one firm could do the job much cheaper than four: there would be no competition for labour; materials could be purchased in quantity; and, perhaps most important, the line could be built in an orderly and progressive manner so that the newly laid rails could be used to transport materials to the unfinished portion.

At thirty-seven, Onderdonk was known as a seasoned contractor with a reputation for promptness, efficiency, and organization. He had just completed the massive sea-wall and ferry slips in San Francisco on time, in spite of serious troubles with the incendiary labour chieftain, Dennis Kearney, a one-time sailor who rose to power as a coolie-hater and was prominent in the riots of 1877. Onderdonk made it clear to the government that he would have the entire 127 miles between Emory’s Bar, at the start of the Fraser Canyon, and Savona’s Ferry, near Kamloops – or he would pull out. He got what he asked for.

Some time later, when the government let the rest of the British Columbia line from Emory’s Bar to Port Moody on the coast, Onderdonk was again awarded the contract, though again he was not the lowest bidder. Certainly in this instance, if not before, the government made use of some fancy sleight-of-hand to ensure that he was successful. Under the terms of tendering, each firm bidding was required to put up substantial security to prove it could undertake the work. The lowest bidder,

Duncan, McDonald and Charlebois, deposited a cheque, which was certified for a specified period. Tupper waited until this period had expired; then he awarded the contract by default to Onderdonk, whose bid was $264,000 higher. This was barefaced favouritism. There was a howl from the Opposition and its newspapers (“a gross fraud,” cried the

Globe)

, but Tupper made it stick. There was another suspicious aspect to the case. For the first time the contract was let as a lump sum, without being broken down into component parts. This method, as the

Globe

pointed out, “is essentially a corrupt method, and is so considered by contractors.” For one thing, it made it difficult to check up on extras. Normally, the government’s practice was to supply its own estimates of quantities to the competing firms. In this case it declined to do so, thereby putting an enormous financial burden on each company tendering. Clearly, the government wanted Onderdonk to have the job, which was, admittedly, as difficult a one as had ever faced a contracting firm in the Dominion. As Henry Cambie wrote: “No such mountain work had ever been attempted in Canada before.”

The first four Onderdonk contracts were signed in 1880, before the Canadian Pacific Railway Company came into being. The

CPR

, under the terms of its agreement with the government, would inherit the stretch between Port Moody and Savona’s Ferry on Kamloops Lake. Onderdonk then, unlike Van Horne, was building a railway that he would never have to manage himself once it was completed. It was a considerable distinction and the basis of a long and bitter dispute between the

CPR

and the government in the years that followed the driving of the last spike.

By the time the

CPR

turned its first prairie sod in May, 1881, Onderdonk had been at work for a year, but he had not laid a mile of track. For all of those twelve months, the people of Yale had grown accustomed to the ceaseless reverberations caused by rock being blown to bits twenty-four hours a day. There were, within a mile and a half of the town, four tunnels to be drilled; it took Onderdonk eighteen months to blast them out of the rock of the canyon – a compact granite, striped with extremely hard veins of quartz. Mountains of this granite – the toughest rock in the world – border both sides of the river, rising as high as eight thousand feet. In the first seventeen miles upriver from Yale there were no fewer than thirteen tunnels; between Kamloops and Port Moody there was a total of twenty-seven. The sixty-mile stretch of road between Emory and the Thompson River was considered to be the most difficult and expensive on the continent. The blasting was painfully slow; even when the big Ingersoll compressed air drills were used, it was not possible to move more than six feet a day. The flanks of the mountains were grooved by deep canyons; as a result, some six hundred trestles and bridges were required above Yale. One hundred of these were needed in a single thirty-mile section. To build them Onderdonk would need to order forty million board feet of lumber.