The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (9 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

Private Peter Thompson of C Company had been in the Seventh Cavalry for nine months and as a consequence was considered a “trained veteran.” In that time, he’d been taught how to groom his horse, cut wood, and haul water, but he’d learned almost nothing about his Springfield single-shot carbine, a weapon with a violent kick capable of badly bruising a new recruit’s shoulder and jaw. Years later, Thompson admitted to his daughter that he’d been scared “spitless” of his carbine, which in addition to being powerful, was difficult for a novice to reload.

Since the pay was miserable, the army tended to attract those who had no other employment options, including many recent immigrants. Twenty-four-year-old Charles Windolph from Bergen, Germany, was fairly typical. He and many other young German men sailed for the United States rather than fight in their country’s war with France. But after a few months looking for work, Windolph had no choice but to join the American army. “Always struck me as being funny,” he remembered, “here we’d run away from Germany to escape military service, and now . . . we were forced to go into the army here.” Twelve percent of the Seventh Cavalry had been born in Germany, 17 percent in Ireland, and 4 percent in England. The regiment also included troopers from Canada, Denmark, Switzerland, France, Italy, Sweden, Norway, Spain, Greece, Poland, Hungary, and Russia.

In August of 1876, the reporter James O’Kelly, a former soldier of fortune from Ireland, witnessed a remnant of the Seventh gallop out to meet what was believed to be a large number of hostile Indians. It proved to be a false alarm, but the maneuver nonetheless took its toll on the troopers. Of Captain Thomas Weir’s company, no fewer than twelve men fell off their horses, with two of them breaking their legs. “This result,” O’Kelly wrote, “is in part due to the system of sending raw recruits, who have perhaps never ridden twenty miles in their lives, into active service to fight the best horsemen in the world, and also to furnishing the cavalry young unbroken horses which become unmanageable as soon as a shot is fired. Sending raw recruits and untrained horses to fight mounted Indians is simply sending soldiers to be slaughtered without the power of defending themselves.”

O’Kelly knew of what he spoke, but the fact remained that the Seventh was, before it lost several hundred of its finest men at the Little Bighorn, one of the better-trained cavalry regiments in the U.S. Army. Lieutenant Charles King also witnessed the advance of the Seventh on that day in August 1876. What struck him was not the ineptitude of the raw recruits but how Custer’s influence was still discernible among the more experienced troopers when the regiment threw out a skirmish line across the plain. “Each company as it comes forward,” King wrote, “opens out like the fan of a practiced coquette and a sheaf of skirmishers is launched in front. Something of the snap and style of the whole movement stamps them at once.”

Perhaps it was Private Windolph who best described the pride inherent in being a veteran member of Custer’s regiment. “You felt like you were somebody when you were on a good horse, with a carbine dangling from its small leather ring socket on your McClellan saddle, and a Colt army revolver strapped on your hip; and a hundred rounds of ammunition in your web belt and in your saddle pockets. You were a cavalryman of the Seventh Regiment. You were part of a proud outfit that had a fighting reputation, and you were ready for a fight or a frolic.”

B

y the second week of the march, General Terry had become fed up with Custer’s tendency to stray from the column. On May 31, the regiment became seriously lost, and Custer was nowhere to be found. That evening, Terry officially chided his subordinate for having “left the column . . . without any authority whatever.”

Custer, it turned out, had been off skylarking with his two brothers. As he giddily described in a letter to Libbie, he and Tom had left their younger brother Boston picking a pebble from the hoof of his horse, sneaked up into the surrounding hills, and then fired several shots over their unsuspecting brother’s head. Boston, of course, assumed he’d been attacked by Indians and started to gallop back to the column. “Tom and I mounted our horses and soon overhauled him,” Custer wrote. “He will not hear the last of it for some time.”

Even though he’d been indulging in immature horseplay in the midst of the most important campaign of his and Terry’s post–Civil War careers, Custer was hardly contrite. That night he responded to Terry by letter. “At the time . . . I was under the impression that . . . I could be of more service to you and to the expedition acting with the advance than elsewhere,” he wrote. “Since such is not the case, I will, with your permission, remain with, and exercise command of, the main portion of the regiment.”

That night a violent snowstorm blanketed the column in more than half a foot of snow. For the next two days, they waited for the weather to improve. The snow was particularly bad on the enlisted men, whose dog, or pup, tents had no heat source. They spent the day huddled around smoky outdoor fires, the snow accumulating on their hats and shoulders as they clasped themselves in a futile effort to stave off the cold.

Custer’s scout up the Little Missouri River had proven that Sitting Bull and his warriors were not where Terry had once assumed they’d be. “I fear that they have scattered,” Terry wrote his sister in St. Paul, “and that I shall not be able to find them at all. This would be a most mortifying & perhaps injurious result to me.

But what will be will be.

”

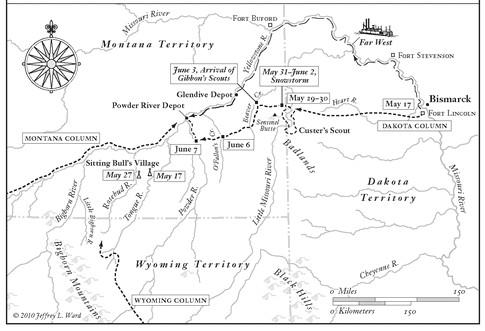

Terry had a portable Sibley stove set up in one of the two spacious tents that constituted his headquarters, which he shared with his aide-de-camp and brother-in-law, Colonel Robert Hughes. A lawyer by training, Terry was careful and analytical, and now that it was clear the Indians had moved off to the west, he pondered what to do next. In accordance with Sheridan’s plan, there were three columns of troopers headed toward south-central Montana: Terry’s 1,200-man Dakota Column approaching from the east; Colonel John Gibbon’s 440-man Montana Column approaching from Fort Ellis near Bozeman to the west; and General Crook’s 1,100-man Wyoming Column approaching from Fort Fetterman to the south.

With hundreds of miles between them, Terry and Crook (who did not like each other) were operating in virtual isolation. A horse-mounted messenger might have covered the distance between them in a matter of days (assuming, of course, he was able to evade the hostile Indians), but at no time during the campaign did either general make a serious attempt to contact the other.

—THE MARCH OF THE DAKOTA COLUMN,

May 17-June 9, 1876

—

This was not the case with Terry and Gibbon, who planned to link up at a rendezvous point on the Yellowstone River. Now that Terry knew Sitting Bull was not on the Little Missouri, he was desperate for news from Gibbon to the west. As it so happened, on June 3, the day the column broke camp after the snowstorm, three horsemen were spotted riding toward them from the northwest. They proved to be scouts from the Montana Column with a dispatch from Gibbon.

In obedience to Terry’s earlier orders, made when the Indians were thought to be on the Little Missouri, Gibbon was making his way east along the north bank of the Yellowstone. Almost as an aside, Gibbon reported that his scouts had recently sighted an Indian camp “some distance up the Rosebud.” This meant that Gibbon was now marching

away

from where the Indians had last been seen.

That night Terry overhauled his plan. Gibbon was to halt his march east and return to his original position on the Rosebud River. Since the Indians were so far to the west, Terry must move his base of operations from the original rendezvous point in the vicinity of modern Glendive, Montana, to the mouth of the Powder River, approximately 50 miles up the Yellowstone. In the meantime, Terry and the Seventh Cavalry were to march west, with a slight jog to the south to avoid another patch of badlands, to the Powder River. After three weeks of hard marching, they were, it turned out, only halfway to their ultimate destination, about 150 miles to the west.

Over the course of the next week, they encountered some of the worst country of the expedition—a sere and jagged land cut up by deep ravines and high ridges, bristling with cacti and prickly pear. An acrid smoke billowed from burning veins of lignite coal. In the alkaline bottomlands, chips of satin gypsum sparkled in the sun. But it was the blue cloudless sky that dominated everything. The troopers had a saying—“the sky fitting close down all around”—that ironically captured the oppressive sense of containment that even an experienced plainsman felt when surrounded by so much arid and empty air. They all wore hats, but the men still suffered terribly beneath the unrelenting sun. “My nose and ears are nearly all off and lips burned,” Dr. James Madison DeWolf recorded in his diary. “Laughing is impossible.” DeWolf now understood why Custer and so many of his officers hid their lips beneath bushy mustaches.

On the night of June 6, they were encamped on O’Fallon Creek with thirty-five miles of even worse country between them and the Powder River. That day, the scout upon whom Terry had come to depend, the quiet and courtly Charley Reynolds, became so hopelessly disoriented that he led them six miles to the south before realizing his mistake. None of the guides, including the Arikara scouts, knew anything about the badlands between them and the Powder River. Terry asked Custer if he thought it possible to find a passable trail to the Powder. Custer predicted he’d be watering his horse on the river by three the next afternoon.

Custer took half of his brother Tom’s C Company, along with Captain Weir’s D Company. They had been riding west into the rugged hills for nearly an hour when Custer ordered Corporal Henry French to ride off in the direction of a spring Custer had seen earlier. French was to determine whether the spring might be useful in watering the column’s horses. As French went off in one direction, Custer, with only his brother Tom accompanying him, set out to the west at a furious clip, leaving the rest of the troopers “standing at our horses’ heads until his return,” Private Peter Thompson remembered. “This action would have seemed strange to us had it not been almost a daily occurrence,” Thompson wrote. “It seemed that the man was so full of nervous energy that it was impossible for him to move along patiently.”

Custer had grown into manhood during the Civil War, when the frantic, all-or-nothing pace of the cavalry charge came to define his life. “The sense of power and audacity that possess the cavalier, the unity with his steed, both are perfect,” remembered one Civil War veteran who attempted to describe what it was like to charge into battle. “The horse is as wild as the man: with glaring eye-balls and red nostrils he rushes frantically forward at the very top of his speed, with huge bounds, as different from the rhythmic precision of the gallop as the sweep of the hurricane is from the rustle of the breeze. Horse and rider are drunk with excitement, feeling and seeing nothing but the cloud of dust, the scattered flying figures, conscious of only one mad desire to reach them, to smite, to smite, to smite!”

But Custer was something more than the harebrained thrill junkie of modern legend. Over the course of the war, he proved to be one of the best cavalry officers, if not

the

best, in the Union army. He had an intuitive sense for the ebb and flow of battle; his extraordinary peripheral vision enabled him to capitalize almost instantly on any emerging weaknesses in the enemy line, and since he was always at the head of a charge, he was always

there,

ready to lead his men to where they were needed most. Like many great prodigies, he seemed to spring almost fully formed from an unlikely, even unpromising youth. But if one looked closely enough, the signs of his future success had been there all along.

He’d been a seventeen-year-old schoolteacher back in Ohio when he applied to his local congressman for an appointment to West Point. Since Custer was a Democrat and the congressman was a Republican, his chances seemed slim at best. However, Custer had fallen in love with a local girl, whose father, hoping to get Custer as far away from his daughter as possible, appears to have done everything he could to persuade the congressman to send the schoolteacher with a roving eye to West Point.

Custer finished last in his class, but it was because he was too busy enjoying himself, not because he was unintelligent. Whenever the demerits he’d accumulated threatened to end his days at the Point, he’d put a temporary stop to the antics and bring himself back from the brink of expulsion. This four-year flirtation with academic disaster seems to have served him well. By graduation he’d developed a talent for maintaining a rigorous, if unconventional, discipline amid the chaos. Actual battle, not the patient study of it, was what he was destined for, and with the outbreak of the Civil War he discovered his true calling. “I shall regret to see the war end,” he admitted in a letter. “I would be willing, yes glad, to see a battle every day during my life.”

His rise was meteoric. He started the war in the summer of 1861 as a second lieutenant; by July 3, 1863, just two years later, he was a freshly minted twenty-three-year-old brigadier general at the last, climactic day of the Battle of Gettysburg. As Confederate general George Pickett mounted his famous charge against the Union forces, a lesser-known confrontation occurred on the other side of the battlefield. The redoubtable Jeb Stuart launched a desperate attempt to penetrate the rear of the Union line. If he could smash through Federal resistance, he might meet up with Pickett’s forces and secure a spectacular victory for General Lee.