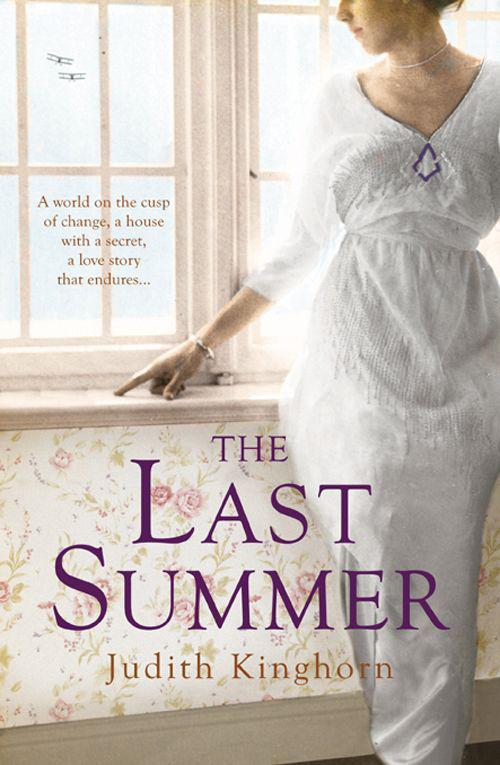

The Last Summer

Copyright © 2012 Judith Kinghorn

The right of Judith Kinghorn to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2012

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978 0 7553 8600 0

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

A PERFECT LIFE

Clarissa is almost seventeen when the spell of her childhood is broken. It is 1914, the beginning of a blissful, golden summer – and the end of an era.

A CHANGING WORLD

Deyning Park is in its heyday, the gardens filled with the scents of roses and lavender, the colours of the earth rich and vibrant, the large country house filled with the laughter and excitement of privileged youth preparing for a weekend party. When Clarissa meets Tom Cuthbert, home from university and staying with his mother, the housekeeper, she is dazzled. Tom is handsome and enigmatic; he is also an outsider. Ambitious, clever, his sights set on a career in law, Tom is an acute observer, and a man who knows what he wants. For now, that is Clarissa.

AN UNDENIABLE LOVE

As Tom and Clarissa’s friendship deepens, the wider landscape of political life around them is changing, and another story unfolds: they are not the only people in love. Soon the world – and all that they know – is rocked by a war that changes their lives for ever.

Sweepingly epic and gloriously intimate, THE LAST SUMMER is a beautiful and haunting story of lost innocence and the power of enduring love.

Judith Kinghorn was born in Northumberland, educated in the Lake District, and is a graduate in English and History of Art. She lives in Hampshire with her husband and two children.

To Jeremy.

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows.

No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass.

No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night.

No time to turn at Beauty’s glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance.

No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began.

A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

William Henry Davies

Chapter One

I was almost seventeen when the spell of my childhood was broken. There was no sudden jolt, no immediate awakening and no alteration, as far as I’m aware, in the earth’s axis that day. But the vibration of change was upon us, and I sensed a shift: a realignment of my trajectory. It was the beginning of summer and, unbeknown to any of us then, the end of a

belle époque

.

If I close my eyes I can still smell the day: the roses beyond the open casement doors, the lavender in the parterre as I ran through; and grass, lambent green, newly mown. I can feel the rain on my face; hear my voice as it once was.

I can’t recall exactly who was there, but there were others: my three brothers, some of their friends from Cambridge, a few local people, I think. Our adolescent conversation was still devoid of any faltering uncertainty, and we didn’t stand on the brink, we ran along it, unperturbed by tremulous skies, sure of our footing and certain of sunshine, hungry for the next chapter in our own unwritten stories. For lifetimes – lifetimes we had only just begun to imagine – stretched out

before us criss-crossing and fading into a distant horizon. There was still time, you see. And the future, all of our futures, lay ahead, glistening with promise, eternal with possibility.

I can hear us now; hear us laughing.

That morning, as clouds gathered overhead, the earthbound colours of my world seemed to me more vibrant than ever. The gardens at Deyning were always at their best during June and early July. It was then, during those few precious weeks of midsummer that the place came into its own. And though Mama had often looked anxious, complaining about the incessant battering of her roses, every well-tended bloom and leafy branch appeared to me luminous and fresh. From the flagstone terrace the lawns spread out in an undulating soft carpet, and on the mossy steps that led down to the grass wild strawberries grew in abundance.

I can taste their sweetness, even now.

Mama had predicted a storm. She’d informed us that our croquet tournament may have to be postponed, but not before people had arrived. So we’d all stood in the ballroom, which my brothers and I simply referred to as ‘the big-room’, looking out upon the gardens through the open casement doors, debating whether to go ahead with our game or play cards instead. Henry, the eldest of my three older brothers, took charge as usual and voted that we go ahead in our already established teams. But no sooner had we arranged ourselves with mallets upon the lawn than the heavens opened with a reverberating boom, and we all ran back to the house, shrieking, soaking wet.

‘Henry wishes tea to be served in the big-room, Mrs Cuthbert. We’re all back inside now,’ I said, standing by the green baize door, wringing out my hair.

Mrs Cuthbert had been our housekeeper for only a few weeks at that time. Years before she’d been employed by Earl Deyning

himself, not only at Deyning Park – now our home – but also at his estate in Northamptonshire. It had been lucky for us that Mrs Cuthbert had agreed to come back to Deyning after the old Earl died, and my mother was delighted to have a housekeeper who knew the place so well. ‘Such pedigree,’ Mama had said, and I’d immediately imagined a little dog in an apron and mobcap.

‘And how many of you are there, miss?’ Mrs Cuthbert asked, glancing over at me, smiling.

‘Oh . . . fourteen, I think. Shall I go and count again?’

‘No, that’s quite all right, dear. I’ll come through myself and see.’ She wiped her hands on her apron. ‘You’ve got my Tom with you today,’ she said.

‘Tom?

Your

Tom?’

‘Yes, he came home yesterday, and your mother kindly invited him to join today’s little game. Have you not been introduced?’

‘No. Well, I’m not sure. I don’t think so . . .’

I followed Mrs Cuthbert along the back passageway, towards the big-room, and I remember looking down at the red and black quarry-tiled floor, trying – as I’d done since childhood – not to step on the black ones. But now it was impossible. My feet were too big.

‘He’s not like your brothers, miss,’ she said, turning to look at me. ‘He’s a gentle soul.’

In the big-room, everyone had already seated themselves around the four card tables pushed up together. And suddenly I was aware of a new face, dark eyed and solemn, staring directly at me. As Mrs Cuthbert introduced me to her son, I smiled, but he didn’t smile back, and I thought then how rude. ‘Hello,’ I said, and he stood up, still not smiling, and said, ‘Pleased to meet you,’ then looked away.