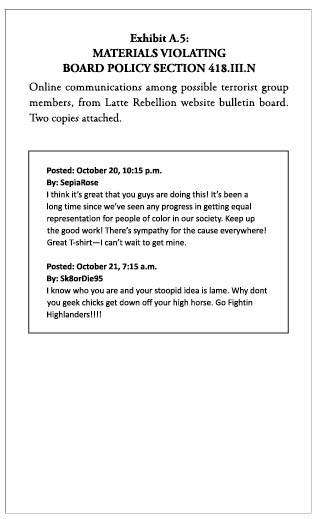

The Latte Rebellion (9 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

“We’ll keep you posted,” Miranda said.

“Can hardly wait.” Mr. Rosenquist gave a little wave and strode off toward the teachers’ lounge.

We opened the door to the Student Council office, where we were meeting with a representative from the Inter-Club Council and one of the ICC teacher advisors to get the Latte Rebellion approved as an official student organization. But as soon as I saw who was sitting behind the round table in the cramped, institutional-green-painted room, I felt my stomach drop to the bottom of my lucky tennis shoes.

Wouldn’t you know it. Our Inter-Club Council representative was Roger Yee. He was sitting there smirking with unrestrained glee, and I knew immediately that this wasn’t going to go well. And Vice Principal Malone, sitting next to him, was just plain scary. Ms. Allison may not have liked her job, but Mr. Malone didn’t seem to like

students

.

“Have a seat,” Mr. Malone said impassively. I handed over our paperwork and Miranda and I both slid into our chairs without a word, exchanging a meaningful glance.

“Let’s see here … ” Roger drawled out each word with obvious enjoyment. He shook his head, his trendy, shaggy haircut immobile with hair gel. “The Inter-Club Council has reviewed your proposal for a new organization—for mixed-race students, isn’t that right? Interesting, interesting … but we are

so

sorry to report that your proposal has been declined.” He pursed his lips in mock regret, looking right at me.

“But Mr. Malone,” I said, feeling anger start to rise, “we meet all the requirements. Mr. Rosenquist said he’d be the teacher advisor.”

“I’m sorry,” Mr. Malone said, sounding completely uninterested in the proceedings, “but that’s what the ICC recommended. I read their report and I found it convincing. They just aren’t sure your idea has the staying power to be viable, and there are already a huge number of ethnic clubs on campus.”

Yeah, I thought, glaring at Roger. Like the Asian American Club. Well, he could have his club full of flunkies and yes-men. I, for one, was

not

going to be yet another groupie of the Bimbocracy. I stood up.

“Asha, hang on,” Miranda said. “Roger, Mr. Malone, you know we have a good case here for this club. We’ve met the requirement of six registered members from the student body. I don’t see why you’d just reject our proposal out of hand.”

“Oh, we considered it carefully,” Roger said, flipping his pen around his fingers in a most annoying and show-offy fashion. “We just feel that your purpose is a little too

vague

to demonstrably benefit the University Park High community.”

Roger, I was starting to see, was as full of crap as an overflowing toilet, and about as delightful to be around. I’d be willing to bet he hadn’t even

read

our proposal. I pushed in my chair and grabbed our paperwork out of Roger’s hands. Miranda stood up, too.

“Fine,” I said through gritted teeth. I tried valiantly to think of a clever parting shot, but I couldn’t. Instead, I forced out a quick “Thank you for your time” and headed for the door, Miranda right behind me.

This was clearly unfair. Just as clearly, something had to be done. And I knew exactly what I wanted to do.

The first general meeting of the unapproved, unofficial Latte Rebellion was held on Halloween night at Mocha Loco. Carey, Miranda, and I were all wearing our T-shirts, along with brown paper bags on our heads that we’d cut down to size, with jack-o-lantern holes cut out for our eyes and mouths—partly for fun, since it was Halloween; partly because it matched the shirts; and partly because none of us wanted to become gossip fodder at school. Plus it let us keep our aura of mystery, let us be our alter egos tonight.

It was 7:45, fifteen minutes before the meeting was supposed to start. Nobody was here yet that we were aware of, except for Leonard, who was working behind the register.

“Is everything ready?” Carey fiddled nervously with the ballpoint pen she’d been using to write up our meeting agenda. Convincing her to come—and take minutes—had been a lengthy process involving several consecutive days of whining, a substantial chocolate bribe, and repeated reassurances of our total anonymity.

“I think we’re set.” To be honest, I was just as nervous as she was. Maybe more so, since I was supposed to do most of the talking.

“You’ll do great,” Miranda said, rocking back and forth in her rickety wooden chair. “This is going to be amazing! When’s your cousin supposed to get here?”

“Any time now.” I grimaced behind my paper bag. “And if she brings her roommate, that means an official head count of … seven.” I drank a sip of the latte I’d already ordered to get myself amped up for the meeting.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Miranda said. “Judging from the comments on your website, at least a few people from U-NorCal are coming.”

“Yeah. I saw that too.” Carey sounded even more edgy at the prospect of college students coming, even though she’d had no problem with inviting Leonard. Leonard, who we’d had to add to the list of Sympathizers on the website, and who threw off our alphabetical order of aliases by insisting on skipping Echo and going straight to Foxtrot. Pretentious, interfering friendship-wrecker.

“I don’t know if U people are going to want to come to a high school thing,” I said. “Just the thought gives me performance anxiety.”

“Are you kidding? Having college students come to your meeting is great,” Miranda said. “You could drum up some serious interest. And hey, you don’t want to run the Rebellion for the rest of your life, right? This way you can kind of … fish around a little for someone to take over.” She straightened her paper bag. “A successor, if you will.”

“A successor?” I’d just figured that eventually our scheme would run its course, we’d have our money, and that would be it. The End. I was still getting used to the idea of this being an actual

group

, let alone finding someone to take it over after we were done, or had started college, or whatever.

“

I

think finding a successor is a great idea,” Carey said, her mask rustling a little as she shifted position in the hard wooden chair. “I’m already feeling burned out just from preparing this meeting. And we have that calculus test on Monday.”

“Ugh,

don’t

remind me.” To distract myself, I looked at the agenda again, written in Carey’s tiny, crabbed, perfectly neat writing. I was going to start off with the introductions and manifesto, Carey was in charge of pushing T-shirts, and we’d all three contribute to the Q and A session. I hoped Bridget would help, too.

As if on cue, the door opened, letting in a swirl of crisp air and a few stray leaves along with Bridget and Darla. Bridget was wearing her Rebellion T-shirt, and I laughed when I saw what she was wearing along with it—a black fedora, ripped black jeans, and dark glasses.

“Hey, if it isn’t the whole wrecking crew,” she said, putting a half-empty bag of Halloween candy on the table.

“What’s this?” I stared at the candy with mock incredulity. “We can’t buy an airline ticket with fun size M&Ms.”

“Har har. It’s so you can feed your constituents something. Everyone likes free food.” Bridget sat down at the small round table next to us.

“You three look so

cute!

I can’t wait to get my shirt, you guys,” Darla said before making a mad dash for the coffee counter. The Rebellion shirt would be a decided improvement, since she was currently wearing a baby tee with Sailor Moon’s sickeningly cute bug-eyed face on it.

“So what’s in store for tonight?” Bridget asked, putting her hot pink Chuck Taylors up on the chair next to her. I pushed the agenda over toward her and she ran one finger down the list, scanning it quickly.

“Lookin’ good,” she said. “What’s your plan for the discussion session?”

“Well,” Miranda said—this was her brainchild—“we were going to ask if anybody had anything to say about the ideals of the Latte Rebellion … any thoughts about what to do at our next meeting. What we should do in the future to encourage appreciation of brown people and mixed ethnicity. That kind of thing.”

“That should be interesting,” Bridget said, a little too neutrally.

“What do you mean?” I looked at her sharply.

“Nothing, really; just that there are people already talking about it. I know this … uh … outspoken girl from my English class is coming, and she was pretty fired up about it.” Bridget reached for the bag of M&Ms and took out a packet.

I didn’t want to think about it. “Thanks for spreading the word, I guess.”

“No problem. Still coming to Students for Social Justice tomorrow?” She glanced at me, then Miranda.

“After this?” I thought about it. “Maybe not. I might see how this plays out first.”

“Or you might spend all evening on the phone with

Thad

,” Miranda teased.

I looked away, embarrassed. I still hadn’t called him, and wasn’t sure if I would. I wouldn’t know what to say.

Bridget chatted with us for a couple more minutes, and I nervously downed most of my large coffee. By the time it was nearly empty, I felt jittery and anxious to get started. I glanced around. A few of the tables near us were already occupied. I recognized a handful of people from school, including David Castro and one of his skater friends, Matt Lee. Matt was wearing one of our shirts. So was Maria McNally, a junior who was a notorious overachiever and one of the charter members of our failed school club. I’d always thought she was part Latina, but I couldn’t be certain—and I was the last person to insist someone might be Mexican. Maria had a notepad and mechanical pencil out, ready to take notes, and she’d brought a group of three other juniors.

I felt butterflies in the pit of my stomach; this was already so much more of a big deal than we’d originally planned. But Roger hadn’t given us much of a choice.

By the time I called the meeting to order—banging my empty latte mug on the table to get everyone’s attention—there were about twenty people in our corner of the café, where we’d set several chairs and tables apart and put up a Latte Rebellion poster behind the “head table.” People had been staring sideways at the three of us in paper bags and whispering to each other. Now was the moment of truth.

I swallowed hard.

“Welcome to the first general meeting of the Latte Rebellion.” My voice sounded reedy and shaky, but there was scattered applause and a few sarcastic whoops. “Before we begin, you may be asking yourselves why we’re wearing these paper bags over our heads.”

“Yeah,” a couple of people shouted.

“Take it off! Take it

all

off,” said David Castro, turning to Matt Lee and laughing.

“Order … order!” I banged the latte glass again, feeling like I was in a TV courtroom drama. “We are wearing these paper bags because the Rebellion is not about individuality. It is about our power as a group, as a movement; about the power of our ideas. We don’t want our identities, our appearance, distracting from the cause.”

The meeting area was silent, and all I could hear was the random clinking of coffee cups and rustling of papers. Everyone was looking at me. I could even feel Carey’s and Miranda’s stares from behind their brown paper bags. I took a deep breath, armpit sweat trickling down my sides, and rushed on.

“Having said that, I would like to introduce the key members and Sympathizers of the Rebellion. Some have chosen to remain anonymous, while others choose to show their faces. Yet all are equally important to the movement.” I ran through the list, pointing out Agent Alpha, Captain Charlie, Lieutenant Bravo, Commander Delta, and even Field Officer Foxtrot, who gave a cocky wave from behind the coffee bar.

I then solemnly read through the manifesto. When I got to the part that said “The world must acknowledge you! The world will appreciate you,” people started muttering “yeah!” and “right on!” And when I recited the concluding mantra—“Lattes of the world, unite!”—the whole group actually cheered and clapped. Not like they would for, say, a band, or even a pep rally, but still, it was amazing. Carey and I had written it sort of as a joke. But here were people—a few white, a few black, but mostly every shade of brown—sitting in a café, listening to everything I was saying and

not laughing

.

This was a novel experience

.

But also … really, really cool. I felt a slow and quiet satisfaction spreading through me. And if it hadn’t been for our club proposal getting summarily rejected, this might never have happened.

When we opened up the floor for the Q and A and discussion, of course somebody had to ask “Who

are

you guys, really?”

“If you don’t already know,” Miranda said solemnly, “we can’t tell you.” A few people laughed at that. The girl who asked the question got up and left soon afterward, looking bored, but we still had a bigger group of people than I’d ever expected.

There were a few other comments, and then a girl got up and asked—demanded, really—to read a poem. Carey, Miranda, and I looked at each other. Bridget glanced at me meaningfully; evidently this was the loudmouth from her class.

The girl, who had short, spiky black hair and what could only be described as a pierced face, pulled a piece of paper out of her pocket and cleared her throat.

“For decades upon decades

We have been oppressed

Suppressed

Re-PRESSED into their MOLD!

No longer! A new age has begun

In which nothing is black or white

But like coffee with milk

Latte.”

She paused for breath, and I chose that moment to jump in before anybody else decided to get up and leave.

“That was … an unexpected addition to our evening,” I said. “Thank you, um …”

“Radha,” she said, looking up, surprised. “I have four more stanzas if you want to hear them.”

I was too appalled to speak. There was a brief silence, and then Maria McNally stepped in, waving a hand to get our attention.

“We should read a stanza per meeting,” she said. “Maybe to wind things down at the end.” There was unanimous, possibly ironic, applause. I looked at Maria gratefully and she gave me a tight smile.

“Tonight was just an introduction to the Rebellion,” Miranda added. “But we should have a plan for our next meeting. What do people want to talk about?” Carey pulled out her pen and sat with it poised over her spiral notebook. The room was suddenly filled with enthusiastic shouts, the awkward poetry moment forgotten.

“The accomplishments of brown people!”

“How to start a dialogue about mixed ethnicity!”

“Where to meet hot chicks!” That one was David Castro, not surprisingly. Still, I was thrilled to the core that

we’d

done this. That we’d created a group people actually wanted to be involved in, that meant something to them—something more than just a new T-shirt.

For the first time in my life, maybe, I was doing something meaningful and important. And maybe this was where I belonged: where people appreciated me for being mixed up. It didn’t matter if they couldn’t see my face. I was one of them, and we were the Latte Rebellion.

When I walked through the front gate of University Park High School the following Monday, I screeched to a halt right next to the first bank of freshman lockers. Something was very weird. Sure, the same groups of kids were milling around the locker area and loitering outside various classroom buildings and smoking cigarettes just off school property. But the first thing I noticed was that there was a lot more coffee than usual. People were holding paper cups with cup warmers around them, draining the last dregs before throwing them away, or pouring hot liquid out of thermoses into the little screw-top cups. Even the campus security guard had a Styrofoam cup in his hand.

Of course, it could have just been discount-coffee day at the convenience store down the street, and it

was

a cold November morning.

But it didn’t seem like coincidence after I saw the number of people who were wearing Latte Rebellion T-shirts.

Our

T-shirts. I hadn’t had a chance to check on how many we’d sold by now, but it seemed like every tenth person was wearing one. I counted at least five on the way to my first-period history class alone.

Was the Rebellion really so … popular? Friday night at the meeting, it felt serious but it felt

underground,

like we were an indie band that only a handful of people knew about. I mean, when I wore my T-shirt to the grocery store with my mom earlier that night, all I got were some strange looks and a free sample from the coffee counter.