The Letters (10 page)

Authors: Luanne Rice,Joseph Monninger

What is the point? Understanding, maybe. On-by.

From the very beginning, I knew we belonged together. I’d never known how lonely I was until I fell in love with you. I’d lie beside you and feel you were part of me but somehow not, too, somehow so exotic and unknowable, and I’d feel I could look into your eyes forever, just touching you and caressing your face, your beard, and the way it felt to my hand, and the way my heart would feel as if it was beating outside my rib cage, and we’d just gaze at each other and you’d never look away first. I loved you for that…

I felt such passion for you. I couldn’t sleep when you were away from me, and I couldn’t sleep when you were right there. I felt this huge worry—I could never put it into words, but it felt as if my being couldn’t support such emotion. My body, my spirit, I was afraid I couldn’t handle the intensity. I had never felt so close to anyone, but I wanted even more than what we had—honestly, I think I wanted to be right inside your skin with you.

Because that’s the only way I could hold you for sure. When you went away on assignment, and I mean even early on, before Paul died, I used to imagine you meeting gorgeous, amazing, athletic younger women—and as much as you assured me both that you

did

and that they didn’t matter to you, it took me years to get comfortable with that reality. I finally began to trust you—even more, trust us, you and me…I wasn’t so much like a howling dog anymore, but one who had circled and circled and finally come to rest.

And it got to the point that even when you were gone, I felt you with me. We knew each other so well—that was part of it. You’d say a word and I could finish your thought. You’d touch me, and I’d lean in for more. When you were gone, I’d feel you in bed beside me. And I’d take a walk through the orchard, and I’d hear you egging me on, to climb a tree. I wanted you as much as at the beginning, but gradually I felt safer. You never broke a promise to me, and that counted so much.

All these thoughts swirling around—to have loved you so much, and now to be on opposite sides of the world with the divorce proceeding, and to receive these letters from you, so full of the voice of my husband Sam, yet also full of…it feels like a new life. Your description of the trip is thrilling, and I feel very far away from you.

So going back to Thanksgiving dinner and gratitude as a topic at the meeting—I was really torn, didn’t want to go. But Turner dragged me there—tall, stooped, taciturn Yankee that he is—he reminded me that the holidays are the Bermuda Triangle for alcoholics, a time a lot of us start drinking again, and forced me to sit in the front row of the church hall. And (I can truly see you cringing at the thought of this next part, “sharing” feelings with a roomful of strangers) when we went around the room, and everyone was saying what they felt thankful for—“sobriety,” “my family,” “my new boat,” “a good report from the oncologist,” and when the circle came round to me, I said “Sam’s letters.”

And it’s true. I’m thankful we’re back in touch. In fact, sitting here in the cottage with a fire crackling and fine sleet pelting the windows, I’ve just reread your last letters and can almost, almost pretend you’re right here. Remember when we were together, what a chore it was to get me to go out? I never saw the point of going to parties, or the movies, or the repertory theater when I could just be home alone with you…

So here we are. Sam and Hadley.

So much in your last letters to talk about…Martha—as wonderful as she no doubt is—is like a toothache to me; you know how when you have a cavity, and you can’t stop touching it with your tongue, to see if it’s still there and as bad as you thought? Well, that’s how I feel about her. And yes, what right do I have to even care, etc. etc. etc.?

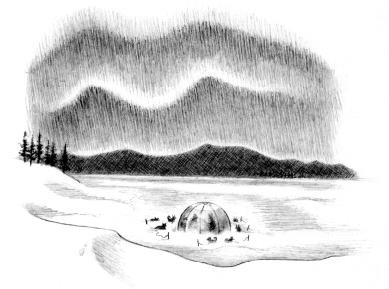

You said she’s smart, and I know how much you like smart people, how swayed you can be by intellect. Not only that, but I read what you wrote and realize I would like her. She sounds great. The part about her saving that team of sled dogs—I love her for it, and you can tell her that. And the fact she bought a hundred acres all by herself, found a way to live on them—if you tell me she has solar panels and is trying for a zero energy footprint (and she sounds like someone who probably does) I’ll love her even more.

That might be why I’m having such a hard time imagining you in such close quarters with her. Because she’s just the kind of person you would love, too.

You tell me what she said about shedding skin. Of course that’s one part of what Paul was doing. I’m not sure we needed her to tell us that. He couldn’t grow and change anymore here at home, because we loved him too much—even being at college he knew we would have done anything for him, and he had to chafe at us, escape from us. Had to drop out of Amherst and upset us, had to rebel, had even to leave Julie, had to fly thousands of miles away. She’s right about that.

But did you tell her how thrilled he was to be accepted into Amherst in the first place? Early decision—that was a strong commitment. Do you remember those months before he applied, when the dining room table was given over entirely to his college essays? Just piles of books and applications and financial forms, and how hard he worked on them all? I’d stand in the kitchen looking at the back of his head, at his messy brown hair, seeing him hunched over writing, and my stomach would hurt because I was so afraid he’d be disappointed. That he wouldn’t get into Amherst.

But he did. I think about it now—how over the moon he was, and I’ll never understand, not really, why he didn’t go back. I know what he told us, about wanting to teach Inuits and help the village—you know I’ve never believed that was all there was to it. I’m sure he was telling the truth about why he wanted to go there—but that came after, didn’t it? Chronologically wouldn’t he have first had to decide he wasn’t returning to college? Did something go wrong that he couldn’t tell us? I know it wasn’t anything to do with Julie—she would have told me. What made him not go back to the college he’d strived to get into early decision, worked so hard for?

I’m thinking of that class he took—LJST. Law, Jurisprudence, and Social Thought…not that he ever would have been a lawyer, but he loved Professor Dunlop, said he changed the way he thought. And I asked Paul once what was so important about that class. He told me they’d had to read Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants.” And I’d read it, and forgotten it, but Paul asked me if I knew what it was about. I thought I did, but he told me—and I didn’t. It was about abortion, even though it’s never mentioned, not even once.

The class had read the story, and they thought it meant one thing, but Professor Dunlop had them stop, and read that part where the girl says, “And you think then we’ll be all right and happy?” And the boy says, “I know we will. You don’t have to be afraid. I’ve known lots of people who have done it.” “So have I,” said the girl. “And afterwards they were all so happy.”

And Paul said they wouldn’t necessarily have realized what it was about, or that the girl was being sarcastic, if the professor hadn’t made them stop and think. The class taught him to look more deeply, that what might seem one way on the surface can be something else entirely down below. People can seem to be talking about one thing when it’s not that at all, it’s something unspoken and maybe even unknown. And he said that gave him a new and completely different way of thinking about life, the ways people interact, the subversive ways we try to persuade people of our points of view.

So does Martha think Amherst—his real and true dream, and those classes he felt were teaching him how to think about the world and justice and art and looking deeply and the green hills of Africa, not to mention Julie—was part of what he needed to shed? You can tell I’m not really resting easy with her theory.

As a matter of fact, I don’t like the snake image. You know I’ve always had a viper thing—used to make you tell me stories about the snakes you saw in Australia and Africa. Snakes and sharks, why do I love you to tell me about creatures that scare me the most? So that bothers me a little, you talking snakes with her.

Do you remember that book by Madeleine L’Engle?

A Wind in the Door

? It came after

A Wrinkle in Time,

and Paul loved it. He loved that it was about a family where the father traveled (you) and the mother stayed home (me) and the children were smart, wry, and unsentimental (him). He loved the fact Meg and Charles Wallace and their twin brothers had a pet snake—Louise. Because anyone could love a cute kitten or puppy, but most people balk at reptiles. Paul was always the champion of the unlovable, the unappreciated. I swear the reason he loved that book so much was that Louise the snake helped save the dying little boy. He had such a good heart, didn’t he? He didn’t distinguish between creatures with fur and those with scales.

Oh, I miss him. Writing about him brings him back. His spirit, his essence, a flash of memory, the sound of his voice. But it’s all so inadequate, compared with the real thing, with my living son. If I could have him with me for one more hour, what would I do? Cut off my arm, certainly. Give my life. I would do that, if I could see Paul again.

We gave our marriage. You realize that, don’t you? Losing Paul made it impossible for us to exist. He died, and we became ghosts. I can sit here and examine what happened. Daniel, my drinking, you disappearing on assignment and even when you were home. But that’s just any old long marriage. People get tired—of their lives, themselves, each other. When a child dies, though, that’s another story. That’s the sky being torn and the earth’s crust being rent, a new plague that affects only your family, and knowing that until you yourself die, every minute will be filled with agony. I was shocked to realize this excruciating pain was made worse by looking into your eyes. Not just because you and he have/had the same eyes, although there is that—but because you gazed upon him as he came out of my womb, took him from the doctor and held him before anyone else, handed him to me. So after the plane crash, when I looked into your sad, hollow eyes, I saw the reflection of that moment and so many that followed. I saw our boy’s life, and that life is no more. And I just couldn’t stand it. It made me, forgive me, unable to look at you.

Enough. I never want to talk about this again.

I’m back. After I wrote that part about kittens and puppies, I realized I hadn’t seen Cat in a few hours. She’s so skittish and feral, and she can hide so completely, days can go by without my seeing her. But the weather is brutal right now, and I wanted to make sure she hadn’t slipped out through one of the cracks.

She was curled up in my sweater drawer. I’ve gotten to know her favorite places, like under the quilt on my bed, so flattened against the mattress no one would ever guess she was there. And, when I’m not burning wood in the fireplace, she likes to jump up into the chimney and hide on the smoke shelf. I always have to look up into the flue with a flashlight before starting the fire to make sure she’s not there. The other day I shined the beam up into the stone chimney, and there were two yellow eyes glowing down at me.

She’s lying beside me now, curled up under the covers, just out of reach of my feet. She likes to be close, but she doesn’t like me to touch her. I’m writing this from bed, because it’s bone-chillingly cold and damp, and because I’m imagining you in Alaska where it’s probably three times colder than this. Do you remember how I used to feel what you were feeling? It was spooky, but when you were near the equator I’d get a fever, and when you went north or far south, when you were near the poles, I’d start shivering and have to put on a sweater.