The Lewis Chessmen (4 page)

Read The Lewis Chessmen Online

Authors: David H. Caldwell

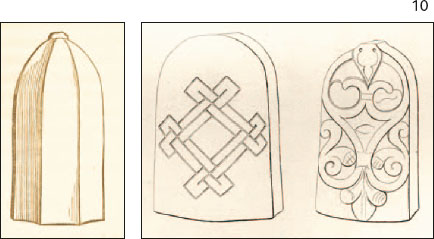

PAWNS

Drawings of the 10 pawns in Frederic Madden's paper in

Archaeologia: or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity

. (

Source:

Society of Antiquaries of London, vol. xxiv, 1832)

The pawns [see

Fig 4.60

] are either slab-like or bullet-shaped and faceted. Two of them have engraved decoration.

Why Twelfth-century Scandinavian?

F

ROM the outset there have been no serious doubts about the Scandinavian origin of the Lewis chessmen. They are mostly made of walrus ivory and that tends to favour a northern European origin rather than one further south, although, undoubtedly, uncarved walrus tusks could readily have been traded for use by craftsmen in centres far away from the seas around Iceland and Greenland where the animals thrived. Useful comparisons have been made between the carving on the thrones occupied by kings, queens and bishops and other ivory carvings with a Scandinavian provenance, with the wood carvings of Norwegian stave churches, and with architectural sculpture in Trondheim Cathedral in Norway â all material datable to the twelfth century. Two other ivory chessmen are known from Scandinavia which are so similar to the Lewis chessmen that they could have come from the same workshop at the same time. One is a knight from Lund in Sweden (in Kulturen, Lund), and the other (now lost) is a queen from Trondheim. Both are fragmentary.

None of this provides proof of a Scandinavian origin, and it has to be said that much of the art and culture of twelfth-century Europe, and clothing and equipment, was truly international, extending from Norway and even Greenland and Iceland, to

Sicily and the Crusader states in the Holy Land. There is one feature of the Lewis chessmen, however, which is difficult to believe could have originated anywhere else but the Scandinavian world, and that is the warders shown biting their shields [

Fig. 4.49

(see

Fig. 9

and image opposite) and

Figs 4.57-59

]. This is believed to indicate that these men were

berserkers

, warriors who fought in an uncontrollable fury, possibly trance induced. Berserkers are said to have fought naked, but it is possible that the carvers of the Lewis chessmen, in showing their warders gnashing their teeth, were deliberately poking fun at some of their contemporaries. The idea is solely Scandinavian and it is doubtful if warriors elsewhere would have chosen to be represented in this way.

In terms of dating, a key consideration is the form of the mitres worn by the bishops. These have peaks or horns, front and back, as mitres worn ever since. It is known that prior to about 1150, bishops wore their mitres with the peaks to the sides. A date about the third quarter of the twelfth century is now generally suggested for the chessmen, and no scholars have dated them any later than the twelfth century. One reason for this is the lack of obvious heraldry on the shields of the knights and warriors. Heraldic designs, as badges of individuals and families, were appearing before the end of the twelfth century.

How Lewis?

F

OR many, Lewis is a remote part of the British Isles, off the beaten track and with a landscape of moors and bogs that does not support a large population. Uig Strand, a desolate, wind-swept area of sand dunes, is just the place that a treasure would be buried, especially if it had come by sea. It is perhaps not surprising that those art historians who have studied the chessmen have assumed that their Lewis provenance was largely accidental. How else could the presence of such fine works of art be explained in such a place? The story of the run-away sailor murdered by the Red Gillie was difficult to swallow. It was much more likely that the hoard belonged to a merchant who was sailing from Scandinavia to markets further south in Ireland or England. Perhaps he was shipwrecked and had to bury his stock as best he could until he could come back and recover it. He may also have hoped to hide the fact that he had landed goods so that he could escape paying hefty tolls to local officials of the King of the Isles. This is what happened to another merchant ship, blown off-course in 1202 and forced to land on Sanday, next to Canna in the Inner Hebrides, as reported by a passenger, Gudmund, bishop-elect of Holar. Whatever the particular circumstances, the person who buried the hoard must have intended rescuing it again and taking it off to somewhere where

fine chessmen could be appreciated. Some other disaster must have prevented this happening.

While this reconstruction of events is plausible, it is by no means the only one. It also pays scant regard to Lewis and what sort of place it was at the time the chessmen were made. In many ways that is the key to gaining a fuller understanding of the hoard.

Lewis and the Kingdom of the Isles

F

ROM the end of the eighth century many parts of the British Isles were subjected to raids by the Vikings, pirates from Scandinavia. In the case of the Western Isles of Scotland these men came from Norway, and by the mid-ninth century many of them were settling down. Local Gaelic-speaking populations were removed, slaughtered or at least suppressed, and the islands became part of a wider Scandinavian world with strong links being maintained with the Norwegian homeland.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the main centre of occupation in Lewis by early Scandinavian settlers was in the parish of Uig. At Cnip Headland there is a pagan Viking cemetery which is the largest known concentration of such burials in the Hebrides. Included is the burial of a wealthy female, with another such interment nearby at Bhaltos School. There is reason to think that the parish of Uig continued to be a relatively important area through the medieval period. The Macaulays, who claimed descent from King Olaf of the Isles (ruled 1226-37), are said, at least by about 1400, to have had their main residence at Chradhlastadh (Crowlista), looking south across Camas Uig to Uig Strand. The main Lewis-based family in the medieval period â the MacLeods â are said to have had a residence on the island of Beà rnaraigh (Great Bernera).

Much of what we know about events in the Isles in medieval times is derived from

The Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles

, seemingly written on the Isle of Man. They tell us that in 1079 Godred Crovan established himself as King of the Isles, and the kings descended from him continued to rule over the Isles until the 1260s. The kingdom included all the Hebrides and the Isle of Man where the kings were based. As time went on, it is clear that Gaelic culture and language re-emerged, so that by the twelfth century the kingdom was a hybrid Norse-Gaelic state. Its kings recognised the overlordship of the Kings of Norway: Kings of the Isles and other local leaders were required to go to the royal court in Norway and Norwegian kings intervened directly in the affairs of the Isles. In 1152, or the following year, the Archbishopric of Nidaros (Trondheim) was created and the new archbishops were given power over the bishops of the Isles, who had authority over all the churches in the kingdom of the Isles. The Hebrides only reverted to Scottish rule by the treaty of Perth in 1266, but the archbishops of Nidaros continued to exercise their power there for some time afterwards.

The authority of the kings descended from Godred Crovan was by no means unchallenged, especially from the mid-twelfth century by a local prince, Somerled, and his descendants, including the MacRuaris, the MacDougalls and the MacDonalds. Somerled defeated King Godred Olafsson in a sea-battle in 1156 and soon afterwards claimed kingship over the Isles. Although Godred reclaimed his kingdom after the death of Somerled in 1164, he and his successors were to find the MacSorleys (Somerled's descendants) troublesome subjects or rivals. In 1249 it appears that King Hakon of Norway was obliged to recognise Ewen (MacDougall) as king over the northern part of the Hebrides. This was an acknowledgement that there was no longer a unitary kingdom of the Isles and that the kings based in the Isle of Man were unable to control other islands. Ewen's territory is not defined and may only have included Skye and Lewis, although he would already have held the Mull group of

islands by inheritance. As Ewen was a subject of the King of Scots for mainland territories, he immediately came under pressure from King Alexander II to give up his Norwegian allegiance. He was forced to flee to Lewis, and his position as King of the Isles was assumed by his main MacSorley rival, Dugald (MacRuari), who remained the main power in the Hebrides, from a Norwegian perspective, until the 1260s.