The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (28 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The prisoners quickly explained that their German guards had fled but that some of the inmates were still locked in their cells with 500-pound bombs on timers ready to explode. Critzas says they called for the nearest explosives ordnance disposal squad to deal with the problem. Questioned about his seemingly nonchalant attitude toward the possibility of large bombs exploding nearby, he said, “We had stuff exploding all around us all the time, and one bomb was like another. Under that kind of pressure and at that age, you don’t feel anything. You don’t know if you’re going to live another day or not. And you just don’t think about that stuff, that’s all.”

His tank unit wasn’t given the opportunity to wait around and learn more about the camp or to help with the survivors. Orders came down from General Patton telling them to “get out of here and keep chasin’ Germans—don’t stop. We’ve got ‘em on the run, we don’t want them to stop and regroup and set up their defenses.” So they left, heading toward Munich.

Many of the men of the 255th Regiment of the 63rd Infantry Division were riding on tanks from either the 10th or 12th Armored Divisions as they moved into the Landsberg area, not knowing what to expect but fearing the worst due to the stench. Staff Sergeant Wayne Armstrong, a rifle squad leader in Company C from Westerville, Ohio, says they were coming down a road when they reached a set of open gates. “We saw all these people in what we called blue-and-white striped pajamas. It was just unbelievable. The tanks stopped, and we’re staring at these people. They looked like they was walking dead. And corpses piled on flatcars. We didn’t know what to make of it.

“These people looked like they was starving, and we started giving them stuff out of our K rations, and it was not too long, word came down not to give them food. We couldn’t figure out how anybody could treat people like that. We’d heard rumors that they had slave labor—but the slave labor they had was in factories and they fed them enough to keep them working, you know. We’d run into a lot of that.”

Domenick Pecchia had been drafted less than six months earlier from the Chicago area, and he was just eighteen when H Company of the 255th found itself at one of the Kaufering camps. His squad was on foot when they came to open gates with prisoners in striped uniforms pouring out. “We kinda hesitated for a moment, but my squad leader said, ‘Get your butt going,’ so we went in. I was horrified. Their condition is what stuck in my mind more than anything else. They were all gaunt and stooped over, and you had the feeling that they were not as old as they looked, you know what I mean? It was a short stay at that particular place, but I can remember it vividly, seeing the little old hats without a brim and the striped uniforms.”

None of the prisoners approached him at that time. “No, no. They were moving. We were going, like, to the left, past the gates over there, and they were streaming out and going to the right. Where they were going—I’m sure somebody else was going to start picking them up and seeing if they needed immediate attention. But we went right on.”

Sergeant Vincent Koch (Kucharsky at the time), a New Yorker, was head of the mortar platoon in Company M of the 255th as they approached one of the Kaufering camps. He’d been in Europe since the previous November and had fought in the Battle of the Bulge. Koch wasn’t aware that there was any concentration camp in the Landsberg area until he and his men were walking down a small dirt road and nearly walked right past one. The gate was open, the Germans were gone, and his squad just walked in, the first Americans to see this particular camp.

“I opened up the doors. The odor coming from there was absolutely unbelievable. And I walked in [the barracks] and they picked their heads up, some of them, they were in a horrible state. They were like double-deckers, some were on the top, others on the bottom. I was able to speak German, so I spoke with them, thinking that it was pretty close to Yiddish. They really couldn’t do much talking, though.

“About three days before that, I received a huge package from home, and there were groceries. And it was in the jeep that was with our outfit. And when I started opening some of the packages, those that were able to got out of their bunks, and they started to walk toward me and the package that I had on the floor there. And that was a big mistake, because they started to claw at each other trying to get to the food. I didn’t realize that that would happen. There was crackers, there was honey cake, there was all kinds of things that they had seen.

“I walked out, and then the captain came back in with me and he said, ‘The smartest thing you can do is take that package out, because they’re going to tear each other apart to get to it.’ We tried our best.”

The discovery of the camp happened in late afternoon. By the following morning, Koch says, ambulances started to arrive.

By the time M Company got to Landsberg, Koch was the only Jew in the outfit. There had been three when the company had been formed in Mississippi, but the other two had been killed. “I was the only survivor with that background, and knowing what the story [of the Nazi persecution of the Jews] was, it was a devastating experience that you remember forever, as you can imagine.

“When we got into the town of Landsberg itself, we started to see the German people, civilians. And I started to discuss it with them, and every single one of them denied that they knew. It was so hard to believe because the stench in that area was so strong that they would have had to know something was going on there. And we took some of the civilians, and we brought them in to show ‘em this particular segment of the concentration camp, and we walked them into where these bodies were lying—you know, the trench. They were horrified, too; whether they put it on or not, it’s very hard to say.”

Tom Malan was a twenty-three-year-old 60mm mortarman with the 63rd Infantry Division on the day it arrived at Landsberg. He’d grown up in Centralia, Illinois, and worked in the oil fields before being drafted. His first combat had been on the Maginot Line, and he had been with the division at the Colmar Pocket. But Kaufering IV—the camp that Israel Cohen was in—was the first concentration camp he saw.

“I will never forget, I ran across a Jewish fellow, I gave him a piece of bread. All he could eat at one time was a little piece, about the size of the end of my finger, because he was thin and had been starving.” The man he fed was outside the camp. The scene that awaited Malan once he walked through the gates and into the camp was also something he’ll never forget.

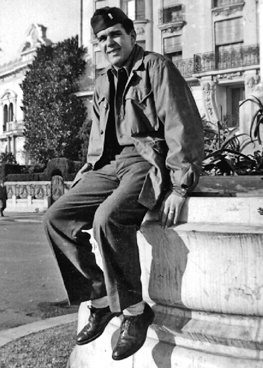

Tom Malan, a mortarman with the 63rd Infantry Division, tried to find survivors among the charred bodies in Kaufering IV, one of the Landsberg camps

.

Before they left in the face of the American onslaught, the Nazis had used the last of their gasoline to set all the barracks in Kaufering IV afire with the inmates locked inside. The Kaufering barracks were about fifty feet long and about fifteen feet wide. They’d been built by first digging a rectangular hole in the ground, perhaps three feet deep. A triangular wall was built at each end, with a door no more than five feet high in the wall at the front. A peaked wooden roof, often covered with dirt, covered the minimalist structure, its eaves going all the way down to the ground. There were no provisions for drainage, so the slightest bit of rain created a mess inside. A central aisle ran from the door to the far end of the structure, and on either side were wooden shelves, usually two decks high, on which the inmates slept.

When Malan came into the camp, all but two of the buildings were still smoldering. Charred corpses were everywhere, some arrested in the act of trying to crawl out beneath the walls. He recalls, “They were burnt from the neck on down—or depending on how far they got out, from their waist on down. They tried to dig out underneath, and they didn’t make it.”

He and his buddies went into some of the barracks that hadn’t been totally consumed by the flames. They were looking for survivors, and he acknowledges that they didn’t go into any more than they had to. All that was left to see was dead bodies.

Malan’s response was to try to get through the camp as quickly as possible, to try to help the survivors who were wandering the camp, one of whom could very easily have been Israel Cohen.

In the final days, it’s estimated that as many as 12,000 prisoners were marched away from the eleven Kaufering camps. Thousands were loaded into boxcars at the nearby railway station. It’s unclear how many of them survived the war.

Cohen says he and his friends saw what was happening when the Germans returned after having run the first time, and they made a decision. “I said, ‘I’m not going to go anymore, I’ve had enough.’”

On April 26, they decided to hide among the sickest prisoners in the camp, people who could be talking one minute and dead the next. “We didn’t care about the consequences, that they were contagious. We were hiding the whole day, the whole night, and then the next day, we didn’t see the Germans. We thought the Germans left. And then they came back. We were hiding there in the belief that the Germans wouldn’t come into those tents. But they did come in, and they evacuated the rest of the people and put them on trucks, these people that couldn’t move. And we were on the trucks. I weighed about seventy pounds, I was skin and bones. We had no strength. But we tried.”

He and one of his friends rolled off the truck when the Germans weren’t looking. They went back into the hut and hid, and they were caught again. And once again they managed to get off the truck and back into the hut. It was nighttime, and Cohen turned off the single light in the hut, and they hid again. Once more the SS came to the door, but this time, they didn’t come in. They stood at the opening and called for anyone inside to come out. Cohen and his friend didn’t move.

The next morning they thought the Germans were gone for good. Some of his friends wanted to celebrate, but he said, “No, we can’t celebrate until the Americans come. Don’t show that we are alive here.” They posted a guard outside to keep watch, and in a short time, he came back in and said that things were not good.

“The Germans came back with dogs, and we’re hiding again, under

shmatas—

rags—and other people were hiding in the straw. They came in, and there were shots and shots and shots. And our luck, one of the people which were hiding in the back by the window got up and they wanted to shoot him, but their gun jammed.”

Several of the prisoners then jumped out the window and hid in the ditches that had been dug behind the hut in preparation for the mass burial of hundreds of bodies. There was more shooting, and Cohen could hear people moaning. Once again, the SS came into the hut and began poking through the straw. Moments later they left and set the structure on fire.

Somehow Cohen and his friend were able to crawl out the door unseen. Nearby was a pile of corpses that had already been soaked with gasoline and burned. They burrowed in among the bodies and lay there. After two hours, he was ready to surrender. “Yeah, then I gave up almost, lying there, and I see that the Americans are still not here, and I said, ‘We can’t go another time, to hide and run around. We’re not able to do it.’ So my friend encouraged me again. He said, ‘Now, you told me in Auschwitz we should not give up, never give up.’ So we lay down.”

They were hiding in the kitchen, a brick building that had not burned, when they heard another inmate shouting,

“Yidden, zaynen frei!”

“Jews, we are free, the Americans are here.”

Cohen remembers thinking about the date—one month after Passover. “I said, ‘It’s Pesach Sheni.’ We are liberated the same day as the second Passover.” (Certain Chasidic Jews recognize a second Passover as an opportunity given to persons who were unable to offer the Passover sacrifice to do so one month later.)

One man whom Israel Cohen wanted to talk about was a friend who had been part of a block of thirty French prisoners. When the Germans left the first or second time, the French inmates took over the kitchen and were boiling potatoes and singing. Then the Germans came back, lined them all up against the wall, and shot them all point-blank. His friend, who spoke German and had the temerity to ask the SS why they were doing that, was also shot, but the bullet went in one check and out the other, and the man pretended to be dead. He was lying on the floor with his mouth open when one of the SS saw that he had gold teeth. Cohen says the SS man took pliers and tore out his teeth, together with the gums. And all the while the man pretended to be dead. “When I came, he stood there with the gums down and the teeth on the gums, and he was bleeding badly.” Cohen says that when the Americans arrived, they rushed the man to a nearby German hospital and in no uncertain terms told the surgeons that if the man died, they would die, too.