The Life of Houses

Read The Life of Houses Online

Authors: Lisa Gorton

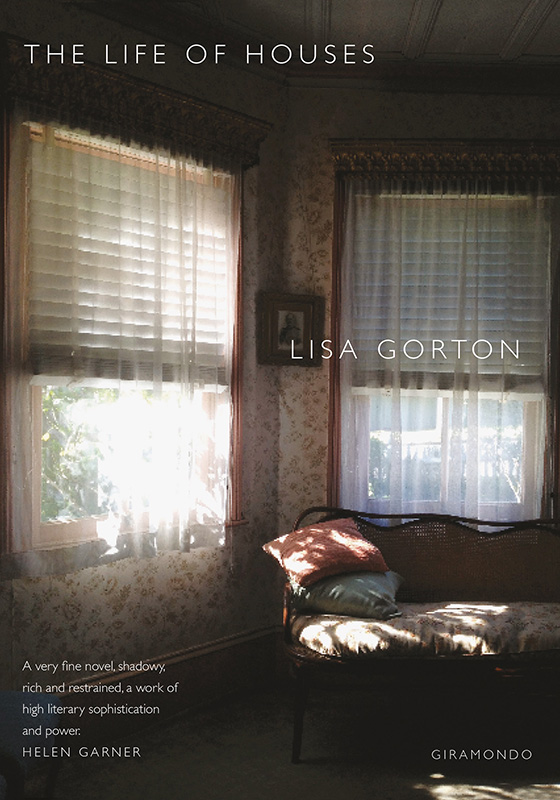

THE LIFE OF HOUSES

ALSO BY LISA GORTON

POETRY

PRESS RELEASE

HOTEL HYPERION

CHILDREN'S FICTION

CLOUDLAND

LISA GORTON

The Life of Houses

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2015

FROM THE WRITING & SOCIETY RESEARCH CENTRE

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY

BY THE GIRAMONDO PUBLISHING COMPANY

PO BOX 752

ARTARMON NSW 1570 AUSTRALIA

© LISA GORTON, 2015

DESIGNED BY HARRY WILLIAMSON

TYPESET BY ANDREW DAVIES

IN 11/14 PT GARAMOND

PRINTED AND BOUND BY LIGARE BOOK PRINTERS

DISTRIBUTED IN AUSTRALIA BY NEWSOUTH BOOKS

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA

CATALOGUING -IN-PUBLICATION DATA :

GORTON, LISA , AUTHOR .

THE LIFE OF HOUSES / LISA GORTON.

9781922146809 (PAPERBACK)

A823.4

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL , PHOTOCOPYING OR OTHERWISE WITHOUT THE PRIOR PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER.

FOR MY CHILDREN

KELSO, TOBY AND PENELOPE

Part I

Chapter One

A

nna was in the habit of arriving early. It had become the part of her evenings with him she enjoyed most simply: this solitude in which she felt closest to the simple existence of knives and forks and spoons. To picture him walking into the restaurant now, walking with that loose kick from the knee, was to feel complications only loosely the same as pleasure. That was what she expected: when he came in she would trade this happiness for pleasure, but the happiness only occurred to her on such termsâ

She had almost finished her drink. Outside her window, less than an arm's length away, the plane tree's leaves turned over in the dry air. She couldn't hear them. Coming here, she had walked upstairs to a different season: the room's wallpaper, even, plumcoloured, and embossed with a climbing pattern of vines. Ornate, decorative, it was not usually a style she could tolerate and yet they met here always; she insisted on it: a world away from her own taste. On the far wall a set of gilt-framed mirrors opened out another room of glassy air. She looked carefully at the middle-aged woman sitting there: a bland half-smile that she had not known she was wearing. Strange: that it would be

that

person he saw. Later, when the restaurant was full, she would forget those

mirrors. Glassy and silent still, they would seem to have fallen behind the noise and life of this room. At this hour, though, the empty restaurant appeared less real than that mirrored one. The light that came broken through the plane trees, and broke again over the table settings, became again one light there. Seeing herself stopped and remote, Anna felt as though she was looking back at something she had already done.

And there he was, down on the streetâthat navy-suited man darting in front of a car. She caught a flash of his hand as he thanked the driver who had slowed for him. To have seen him before she recognised him gave her a sense of detachment, but also of tenderness. She was at once conscious of how much world there was around them; how, lacking shared habits, they had sanctified familiar places: this restaurant, the river walkway to the Gardens, their Sydney hotel: places that lent the weight of fact to meetings that otherwise hung in memory like so many hallucinations. For that moment she was free of the compulsion to see him. The affair seemed no more than an attempt to give meaning to their betrayals: a strange mechanism that drew in their future to justify their past. Almost from the start, she thought, they had been looking back, trying to find out what had made them do what they had done. That first week, which had seemed an escape from time, was the one time they could live in. She thought how simple it would be to stop seeing him, to block his emails, to screen his calls; and felt elated, as though she had achieved this already.

He seemed to shake off the waiter as he crossed the room. Pausing behind her chair, he rested his hands on her shoulders and bent to

kiss the soft indent between her neck and jaw. He dragged his chair around a corner of the table before he sat down. His place setting, across the table from them still, marked the deliberateness of their intimacy. Always, when they met, there was this moment when they forfeited the intervening days; when, stepping out of their own lives, they seemed to step into a noonday glare of feeling. There was something posed about how, in this first moment, they held their gaze apart. She thought: This is how I know him: in three-quarter profile, his knee against mine.

In fact, he looked always a little different from how she had remembered him. Her memory kept still images but he had a thin, fine, mobile face. Five years younger than she was, his face was everywhere marked with wrinkles which, because they emphasised his expression of wariness, made him look younger than he was. He had the self-absorption of sensitive and ambitious people: he was forever watching people to discover what they thought of him. His hair, dark still, he combed back from his forehead. Only one curl, tumbling forwards, justified his nervous habit of brushing his fingers over his forehead.

She said, âHow was the flight?'

He shrugged, smiled and signalled to the waiter for a drinkâgin and tonic, the same as hers; and another for her also. He lent across the table and looked at her. He was always in movement like this; he made a drama of every meeting. It annoyed her, suddenly, and made her brutal.

âSo I've packaged her off.'

âKit? To your parents?' He reached across the table. She looked

down at his handâits few black hairs, the fingers, wide-knuckled, ending in yellowish, squared nailsâand found herself resenting his gratitude: that he should make this matter of her daughter simply a tribute to him. She forced herself to turn her hand and gently tap the underside of his wrist.

âAll the way to the station I had this monstrous desire to be rid of her. I suddenly realised how demoralising these months alone in the house with her have been. We sit at dinner and silence comes out of the furniture. “What did you do today?” “Nothing.” What's so galling is she then spends hours on her phone in her room.'

She caught him looking around for his drink. For all the agitation of his gestures, his manner of speaking was cool and ironic. He said: âShe blames you for her father leaving.'

She shrugged. âWell but her attention to detailâreally, from how much I spend on dry cleaning to how many fingers I use to type messages on my phone. At the station she ticked me off for being rude to the ticket lady. The truth is, I

was

rude to the ticket lady. I'm hypnotised by her contempt for me. I become as dreadful as she thinks I am.'

He smiled abstractedly. She saw that he had lived out this dinner, the start of their first full week together, already in his mind. This was not how it was supposed to start. Kit was not what he had meant for them to talk about. He had told Clare, he had moved out.

Now

, he wanted to sayânow

we

start making plans. She went on: âThe train pulled out and I discovered I was shaking. I had to sit down. Some little gnome of a man in a bowler hat stopped to ask was I alright. The sound of the trainâ'

âKit, though? She was happy to be going?'

âMostly curious, I think. She's never been there. Delighted to escape from me, of course.'

âTo her grandparents? What do you mean she's never been there?' Anna heard disapproval behind what she thought of as the professional neutrality of his voice. Raised a Catholic, he could set aside belief itself, she thought, but not the habit of seeing every human decision in a moral light. For him every placeâthis restaurant, even, with its white napery, its thick carpetâresembled a Mantegna landscape, all stark outcrops and no shade. Strange, she thought, looking mockingly at him, that his disapproval never offended her. She had come to ignore his scruples, even to travesty a little what she felt. For all his nervy fastidiousness he was something of a masochist: he had forfeited self-regard to meet her here. It was almost flattering. Having always doubted what it was that people meant by feeling, he was reassured to find himself in love so much against his better judgement. Even here, in this room of muted good taste, they met intensely: his disapproval made them dramatic to themselves.

She said, âWe went there once, years ago. I doubt she'd remember. Matt wanted to meet themâ'

âThey didn't like him?'

âDarling, they don't

like

anyone. They don't register personality.'

âBut what did they say?'

âNothing. No one said anything.'

âBut you've kept Kit away from them?'

âYou're looking for some hidden reason. The fact is I didn't want

to see them, not when I first got back from London, not till I'd set up the gallery. By that time, I'd stayed away so long I would have needed a reason to go.'

The waiter appeared with their drinksâa movement so timed to Anna's own she realised he must have been waiting for a moment to break into their talk. Anna drew her legs away from Peter's, a withdrawal of physical contact which exaggerated their closeness. The waiter's deliberate innocuousnessâhis pale, slack, smooth cheeks, greenish-blond hairâinsinuated that he noticed as little as possible. They knew the menu by heart. Sitting straight, she and Peter watched each other while the waiter took their orders. Unkindly, they turned to watch him vanish through a swing door, leaving them in the blank stage that is an empty restaurant, this one more implacable for its subtle richness, its impersonal good taste. Watching the door swing back and forth, Anna did not doubt that he had marked them down as illicit loversâthough, how? More than touching, their nervy antagonism declared it: secrecy created a need for outsiders. Only in opposition could the surrounding world exist for them.

She threw off, âThat waiter smiles while he talks.'

Peter paused, one fingertip rubbing condensation from the base of his drink. âIt's strange. I never thought of you having parents.' With a gesture of her hand she pushed the remark away. âNo, but it is odd,' he persisted. âI don't think I even realised you grew up in the country.'

âHardly the country,' she said. âA seaside town.'

âWhich you never go back to.'

âI created myself,' she said, smiling malignly. It was what she said in interviews. All those self-consciously clever young men: they wrote it down without question. Remembering, she turned away to look out at the leaves: never still, how they suddenly lifted sideways and apart. She said, âIt might be the one thing we have in common, how we escaped our background.'

âI see my parents every month.'

âI can imagine. Sunday lunch. They spend all Saturday cleaning the house. Then for an hour they sit around the table shining lights at you, their successful son. Only when you leave they make a cup of tea and put their feet up.'

He laughed. âClare hates it.'

It had often struck Anna as the strangest thing: how little, till now, she had been jealous of Clare. She had pictured Clare as another of the wives at that first dinner party the night when she and Peter had met: couples talking of schools and football coaches and renovations with an iron complacencyâtalk in which whatever was giant in them, and desperate, was shut out; that night when, sitting side by side at that table, saying I and not we, she and Peter had come to exist for each other outside their social lives. She never had learned what had kept Clare away that night.

Crumb-hunters, she called them: people who spent too long saying good-bye, waiting around after openings for some intimate word, as though only lack of time had kept her from speaking with them. When at last they left she always put a red line through their names. At that dinner party, though, the idea of couples had so predominated she and Peter had found

themselves the last to go. She remembered his face as she had seen it then: under a streetlight, unnaturally shadowed, while the last of the couples' cars turned out of the street. They faced each other in that place where, if they had been a couple like the others, their true conversation would have started, the one in which they went over all the evening's talk and discovered for each other its scandals and hypocrisies.