The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (19 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

To what end the struggle now beginning in earnest was tending, few on either side had probably any suspicion. Loyalty, if it was ceasing to be a reality, retained an imaginative existence even amongst those most opposed to Charles' high-handed proceedings. Least of all would the foreign Queen, engrossed in the limited interests, the trifling intrigues, and the pleasures of a court, be in a position to form any adequate conception of the volume of hostility daily gathering force outside it.

With one considerable factor in public discontent Henrietta was intimately connected. Religious feeling was running higher and higher ; and during the yes 1634 and the two succeeding ones, events had taken place contributing distinctly to increase the suspicion with which the ecclesiastical arrangements at court were regarded. Henrietta had hitherto exerted herself onl] spasmodically, and when stirred to the effort by outside influences, to further the spread of her own religion. For the most part she had contented herself with obtaining from the King alleviations of the disabilities applying to its members. But she had, nevertheless, been viewec from the first with distrust by a large party in the nation.

INDULGENCE TO CATHOLICS 157

To the Puritans she was a " daughter of Heth," and on one occasion had been openly and " irregularly " prayed for at St. Sepulchre's Church, the petition taking the form of beseeching that u her eyes might be opened, that she might see Jesus Christ whom she hath pierced with her infidelity, superstition, and idolatry." Andrew Humfrey, one of the seers so rife at the time, wrote to a correspondent, in a note preserved amongst the state papers, that although their noble Queen was angry with him, he " had watched day and night for seven years to keep her Highness out of hell "—by what means he omits to specify. Such isolated expressions of feeling probably represented in an exaggerated form the sentiments of the Puritan body at large.

Under these circumstances it was inevitable that a jealous watch should be kept upon proceedings at Whitehall, and that Henrietta's growing influence over the King should be regarded with disquiet. It was true that the condition of Catholics was still in many ways undesirable enough ; but notwithstanding the acts in force against them, it was undeniable that the severity with which these decrees were applied had been considerably relaxed. " They were grown," says Clarendon, summarising the situation, " only a part of the revenue, without any probable danger of being made a sacrifice of the law." They were fined, that is, but not executed. According to the same authority, they were not discreet in the employment of their new immunities. Grown elate and bold, they resorted to mass at the Queen's chapel with the same " barefacedness " as others to the Savoy ; whilst priests " were departed from their former modesty, and were as willing to be known as to be hearkened to."

Toleration is to be commended, and there are few

HENRIETTA MARIA

at the present day who will be found to condemn it. But it should not be one-sided. In the seventeenth century liberty of conscience had not yet been recognised as a part of the liberal creed, and was no article of faith amongst those most ardently enlisted on the side of political freedom. To the majority of Englishmen, vehemently opposed to the authority from which they had recently broken loose, the indulgence shown to members of the unpopular Church would have been in any case unwelcome. That, almost simultaneously with the exercise of this toleration, culprits accused of errors in an opposite direction should have been savagely punished, placed in the pillory, and mutilated, was likely to kindle a fire of indignation not to be easily extinguished. Nor was the fact that, in 1634, a papal agent had been sent to London and received at court, calculated to allay it.

Though the ostensible object of Gregorio Panzani's mission was to compose the dissensions arising out of the relations of the regular and secular clergy resident in England, there can be little doubt that the desire to gain a footing in London and to establish a channel of communication between Rome and Whitehall was in the minds of those who sent him. Dodd, indeed, himself a Catholic, describes the whole affair as "an intrigue against the Established Church."

The envoy had been carefully selected. As an Oratorian he belonged to the same order as the Queen's confessor, Father Philip, and was so well disposed towards conciliation as to draw down upon himself an occasional rebuke from the Vatican. His mission was inaugurated by an interview with Henrietta, when " he acquainted her Majesty with the extraordinary respect 1 entertained for her by Pope Urban, on account of the

ease enjoyed through her interest by the Catholics of England. Panzani likewise expressed the Pope's desire that her co-religionists should be exact in their civil allegiance, and requested that his arrival should be made known to the King, whose " tacit consent" to his coming had been already obtained.

Charles' reply to the announcement was that the agent was to act with caution and secrecy, and above all was not to intermeddle in affairs of State. So far, therefore, the King's attitude was strictly neutral. Panzani had several interviews with the Secretary, Windebank, who, according to the agent, had authority from his master to discuss the question of re-union. An honest man, though weak and of no great abilities, Windebank had leanings towards Rome leading him ultimately to make his submission and die a Catholic. He was anxious for compromise, not only on the crucial point of the oath of allegiance, always a stumbling-block, but on matters of doctrine. " If only Rome had a little charity! " he sighed. Laud, on the other hand, possibly understanding the attitude of the Holy See better than the layman, was reported to have told the King that, <{ if he wished to go to Rome, the Pope would not stir a step to meet him."

On the subject of the oath it was intimated to the papal agent by certain of the King's Council that it might be modified so as to suit Catholic consciences ; and Panzani, not to be outdone in generosity, encouraged the hope that the Pope might compromise the matter, thereby winning for himself a sharp rebuke from head quarters. He aimed, he was told, at too much ; and it could be wished he had shown more caution in dealing with the oath. He had also been meddling, perhaps unwisely, in the Queen's household. It was better to avoid

tampering with it. His business was to see, hear, and observe.

What the agent did see, hear, and observe, must have been in many respects eminently satisfactory to those to whom his reports were sent. Allowing for his disposition to represent matters at the English court in a favourable light, there was much that was calculated to encourage any hopes of ultimate reconciliation entertained at Rome. Henrietta had taken her little son to mass, promising to do her best to bring him up in her own religion. Montagu, Bishop of Chichester, was keenly anxious for re-union, though contemplating terms that Panzani knew well enough would never be accepted at Rome. In the meantime, he and the agent were on the most friendly footing. He would be a papist one day, the envoy told him. " What harm would there be in that ?" returned the Bishop. Lord Cottington, temporarily associated with Laud at the Treasury, and who ended his life in the Roman Church, took off his hat reverently whenever the Pope's name was mentioned. Walter Montagu, the Queen's playwright and favourite, was transferring his allegiance to Rome. In his case some secrecy seems to have been considered expedient, as Henrietta, writing to her sister, the Duchess of Savoy, mentions that it is probable that Montagu will soon be in her neighbourhood, " it being necessary, for a reason that will not be displeasing to you, that he shall absent himself for a short time"—the cause she fears to commit to paper. Perhaps a more important piece of intelligence than any of the rest had been the announcement that, not four months after Panzani's arrival, the dying Treasurer, Portland, Charles' principal adviser, courteously declining Laud's proffered ministrations on the grounds that, " God be thanked, he was at peace in his conscience," had died in the Catholic

faith. " The Lord Treasurer," wrote Con way to Went-worth, "is gone to give an account of his stewardship. He hath left many mourners for him, but the most are that he did live, not that he did die. Sir Tobie Matthews " —also a convert—" doth assure us he is in heaven. ..." Coming to the important matter of the King himself, Panzani was soon able to report that he had been granted a personal audience and had been received with a very cheerful countenance. The interview was followed by others, though the conversations with Charles always took place in his wife's presence and were confined to general subjects. It was probably on one of these occasions that the Queen, speaking of Pope Urban, told Charles that he had filled the post of nuncio at Paris at the time of her own birth ; and in offering his congratulations to her mother, had said he hoped the time would come when the infant Princess would be a great Queen. " That will come to pass," returned Marie de Medicis lightly, " when you are a great Pope." Both things, the King courteously replied, had manifestly come true. " I always," he added, "looked on our Queen-Mother as a great Princess ; but for the future I must regard her as a prophetess."

Sometimes the conversation turned on more serious matters. " God forgive the first authors of this disunion," the King once said. For the agent he seems to have had a genuine liking. Panzani hoped, he told Charles, that the fact of his being a good servant to the Pope and Cardinal Barbarini would not serve to prejudice him with his Majesty. "The King quickly gave me his hand, saying, ' No, Gregorio, no. Always be assured of that.''

Other scenes of a lighter nature are reported, such as a distribution of objects of devotion, sent for that

VOL. I. II

purpose, amongst the Queen's ladies; when little Geoffrey, the dwarf, moves all present to laughter by his manner and gesture in making his claim to a share. " Madame," he bade Henrietta, " show the father that I also am a Catholic." Henrietta herself, receiving a picture of St. Catherine, is so much enchanted with the gift that, refusing to wait until the agent has had it properly framed, she takes at once possession of it, tin case, pack-thread and all, and orders it to be hung up above her bed. " The opinion of one who was not present is still expected," adds Panzani—not without, one fancies, some satisfaction in the display of independence.

More splendid gifts, especially adapted to the King's well-known tastes, were despatched from Rome in acknowledgment of the redress of certain grievances under which Catholics had continued to labour. Ostensibly presented to Henrietta, they consisted of paintings by the most celebrated of the old masters—Albani, Correggio, Veronese, Stella, da Vinci, Andrea del Sarto, Romano, and others. Their arrival having been announced, it was no wonder that Charles was impatient to inspect these treasures of art; and, Henrietta being confined to her room at the time after the birth of a child, the boxes were opened in her apartment in the presence of both King and Queen, each picture being viewed in turn " with singular pleasure "—although Henrietta, finding none of them of a devotional character, " seemed a little displeased."

Panzani appears to have accompanied the court occasionally to the country, some of his communications to Rome being dated from thence. During his visits there he was evidently not idle. The hostess by whom the court was entertained permitted mass to be said in the chapel, and had gone so far as to ask counsel of the envoy with regard to the practice of confession. Being

answered that it was good, but must be made to a true priest, she responded by a sigh.

The mission of Panzani came to an end at the conclusion of 1636. Those who had sent him may well have been satisfied with the results he had achieved. The most important was the arrangement he had successfully negotiated for the establishment of a permanent agent of the Vatican at Henrietta's court, whilst the Queen was to be likewise represented at Rome. The choice of the men who were to fill posts of such importance had been much debated. Ultimately a Scottish priest named Con was selected by Urban to be resident in London ; whilst William Hamilton, brother to Lord Abercorn, was sent by Henrietta to the Vatican.

The arrangement was certain to meet with sharp criticism in England. Whether or not the labours of Panzani would have conduced to the permanent advantage of the Catholic Church, had not their results been swept away by the convulsions so soon to follow, there can be small question that his achievements contributed to increase to an appreciable degree the irritation of the ' nation towards the Crown and court. It was true that Laud, as well as Juxon, Bishop of London and soon to (* occupy the post of Treasurer, had held themselves absolutely aloof from the papal envoy. " The Papists," the Archbishop is quoted by a correspondent of Went-worth's as saying, " were the most dangerous subjects of the kingdom"—adding that between them and the Puritans the good Protestants would be ground to powder. It is certain that the King himself never wavered for a moment in his allegiance to the Established Church. " I permit you your religion," he is said to have told the Queen ; " the rest of my subjects, I will have them live in the religion I profess, and

164 HENRIETTA MARIA

my father before me." The words were the sincere expression of his attitude throughout, no matter what amenities may have been exchanged between him and Rome. But the public, looking on, was not unlikely to put a different construction upon what they saw. Panzani's mission had certainly given a new impulse to proselytism, gathering, as will be seen, strength in the hands of his successor, Con ; and the more conspicuous conversions at court were earnests of many others in a humbler sphere. Thus the sub-curate of St. Margaret's, Westminster, is found addressing a complaint to the authorities, stigmatising the prevalent interference in spiritual matters as unsettling to poor people and their religion, and adding an argument for the exclusion of the " newly turned Roman Catholics" from the Queen's chapel, more calculated, as he may have shrewdly surmised, to appeal to the King than those based on theological reasons alone. Their presence at Somerset House was not only undesirable on other grounds, but was fraught with danger to the Queen, three persons who had watched with a dying man (probably sick of the plague) having attended mass there next day.

Whilst the progress of Catholicism, together wil the approximation to Roman doctrine and ceremonh within the Established Church, were serving to rouse the jealousy of the growing Puritanism of the nation, two other foreign visitors, of a very different nature tc the papal agent, had arrived at court, and had beer given a hearty welcome by King and country alike These were Charles' nephews, the young Prince Palatine and his brother Rupert. Devoted as Charles had showr himself to the furtherance of his sister's cause—h( had lately been endeavouring through Panzani to induce Urban to interest himself in the question—she herself,

VISIT OF PRINCES PALATINE 165

after her long residence abroad, must have come near to being a stranger to him. Sir Thomas Roe, her principal English correspondent, urging her acceptance of the invitation sent her by Charles upon her widowhood, gave it as a reason that her presence was necessary to establish love and make acquaintance with her brother. Elizabeth had not acted upon his advice, but his argument may have decided her to send her two boys to London, counting upon a personal acquaintance to quicken the King's interest in their futures. At any rate, by December, 1635, the elder of the brothers was in England, Rupert following a few weeks later.

The reception accorded to the disinherited heir to the Palatinate was, as might be expected, cordial. Anxious to emphasise his position from the first, Charles sent the Earl Marshal as his own representative, and Lord Goring as the Queen's, to meet the boy at Gravesend and bring him to London, where he was received by the King " extraordinary kindly," and kissed by Henrietta. " He is a handsome young prince," adds the correspondent who sends Wentworth these details—

Charles was punctilious in matters of etiquette with regard to his nephew. The Spanish ambassador, anxious to ingratiate himself with the King, and reflecting that courtesy costs nothing, took care to give the guest his full title of Prince Elector Palatine ; thereby stealing a march upon the French envoys, who, being " more hidebound," declined to do so without permission from home, and were consequently refused by the King access to the lad. Both at court and elsewhere there was mighty feasting in his honour, Lady Hatton in par-

ticular having provided a huge entertainment, including fireworks, two masques, and a great supper—the whole forced to be deferred for six weeks on account of the inopportune arrival of the little Princess Elizabeth, the night before it was to have taken place. By February—his brother having meanwhile had an attack of measles—Rupert had been sent for, and both were being initiated into the manners and customs of English court life.

Judging by the impression made by them upon Roe, their mother's faithful friend, recorded in a letter to her, the lads were singularly unlike. The elder appeared to him to be of a sweet nature, possessing in especial the virtues of secrecy and sedulity. He could love and discern his servants. His own letters give the impression of a cautious lad, anxious to do his duty, not without an eye to self-interest and somewhat of a prig. All, he wrote to his mother, showed a great deal of desire to serve him, but he would believe nothing but what he saw. A prediction hazarded by him, with regard to some business on hand, to the effect that Henrietta " is so discreet that she will not meddle in it," argues a certain lack of the power of appraising character. He was also much troubled by a report, " spread all over the town, that my Lady Laveston hath given my sister a box on the ear, before twenty people, in the Prince of Orange's garden, and did not so much as ask her pardon for it." The foolish things happening at his mother's court ought not to be repeated, though he for his part cannot believe but that it was a jest.

Rupert was cast in quite another mould. The boy, once more to quote Roe, was of a rare condition, full of spirit and action. Certainly he would " reussir en grand homme," for whatsoever he wills, he wills vehemently.

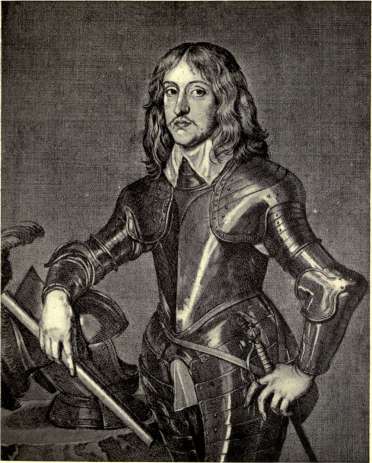

From an engraving after Van Dyck's picture.

CHARLES LEWIS, PRINCE PALATINE.

VISIT OF PRINCES PALATINE 167

His Majesty takes great pleasure in his unrestfulness, for he is never idle, and in his sports serious, in his conversation retired, but sharp and witty when occasion provokes him. His mother furnishes a further sketch of the boy who was subsequently to play so important a part in English affairs. She hopes, she says, for his blood sake he will be welcome, though she believes he will not much trouble the ladies with courting them, nor be thought a very " beau garden." She does not desire that he should linger too long in the atmosphere of a court. He is to learn soldiering under the Prince of Orange, so as to serve his uncle and his brother. And Roe believes—subsequent events justified the belief— that he will " prove a sword for all his friends if the edge be set right."

During their visit the young Prince Palatine kept a wary eye upon his more impulsive brother, and is presently found writing to his mother in some anxiety. Rupert had been making undesirable friends. "My brother Rupert is still in great friendship with Porter "—Endymion Porter, afterwards concerned in the Army Plot with Goring and Jermyn—" yet I cannot but commend his carriage towards me ; though when I ask him what he means to do, I find him very shy to tell me his opinion. I bid him take heed he do not meddle in points of religion amongst them, for fear some priest or other, that is too hard for him, may form an ill opinion in him." Con, the papal envoy at the time, was a frequenter of the house, and Mrs. Porter herself a Catholic. But it is clear that Rupert was not amenable to brotherly authority. " Which way," adds Charles Lewis, " to get my brother away I do not know, except myself go over."

Rupert had taken kindly to English life. Neither

the lads nor their mother had reason to complain of any lack of warmth in the welcome they continued to receive, not only at court, which was a foregone conclusion, but outside it. Partly in compliment to the King, but probably more in consequence of their own popularity as belonging to a branch of the royal house whose Protestantism was unquestioned, London was eager to do them honour. An entertainment on a magnificent scale was in preparation at the Middle Temple, a new feature in the rehearsals being the presence of a sham prince, set up there for weeks beforehand and provided with all the accessories to a sovereign, including ministers of State and a favourite. On the Wednesday before Lent the result was seen. On that day the " Prince of the Temple" invited the Prince Palatine to assist at a masque ; and thither also went Henrietta, accompanied by three of her ladies, all disguised as citizens, and attended by Holland, Goring, Henry Percy, and Jermyn, also in masquerade ; when Mistress Basset, the great lace woman of Cheapside, went foremost, leading the Queen by the hand. When all was over, the Prince of the Temple was deposed and a genuine knighthood replaced his fictitious honours.

With what sentiments Henrietta regarded the King's nephews does not appear. It is possible that she had not forgotten the regrets of the Puritan party that their heirship presumptive to the Crown should have been superseded by the birth of her own son. But she probably owed them no grudge on account of that for which they were in no wise responsible ; and whilst their visit gave occasion for revels such as that in the city, she would not regret it. The novelty of their presence, their youth, and perhaps Rupert's " unrestfulness," may have afforded amusement to her as well as to the King.

During the summer of 1636 Wentworth had reappeared at court, having left his duties in Ireland for a time and come to London to justify his administration in Ireland before the King and Council. Private as well as public charges were preferred against him. Unpopular at court, and more especially on the Queen's side of it, he was reported to have declared that Holland should have lost his head in connection with his conduct with regard to the letters intercepted by Jerome Weston, and however carelessly the words might have been said, the culprit would not forget or forgive them. Nor was Wentworth the man to propitiate public opinion. Even his firm friend, the Archbishop, would have had him assume a more conciliatory attitude. " If you could find a way," he wrote, " to do all these great services and decline these storms, I think it would be excellent well thought on." Wentworth did not act upon the advice, and his unpopularity grew. Judging, however, by a letter addressed to him by Lord Dorset in the year preceding his present visit to London, Henrietta, if she did not like the Lord Deputy personally, had begun to recognise his great value to the King. " How fairly your lordship stands in the Queen's opinion," wrote Dorset, "judge by this relation I give you. Two days since, fame rumouring your death, with sorrow she protested that then the King had lost a brave and faithful servant, one whom she loved, valued, and esteemed." Possibly the tribute to one believed to be dead was not of so much worth as if paid to the living. But Wentworth was not inclined to underrate any token whatsoever of royal favour. " I do understand," he replied, " with much comfort of her Majesty's gracious mentioning of me upon the rumour of my death. I do consider it in silence and gratitude as indeed it doth