The Little Book of the End of the World (17 page)

Read The Little Book of the End of the World Online

Authors: Ken Mooney

As France experienced the depths of an economic crisis, the nobility remained unaffected. With stories of famine and starvation on the streets of Paris, Queen Marie-Antoinette is famously reputed to have said ‘Let them eat cake’. The queen’s words have been interpreted in several different ways: mostly, it is seen as a naive comment that only highlights the monarchy’s failings and inadequate home economics, but others suggest that Marie-Antoinette may have had the makings of a royal heroine, wanting to share the royal coffers and larders with the poorer souls on the streets, but facing resistance from the rest of the court.

The French Revolution was a lengthy affair: over the course of a decade, the aristocracy were overthrown and numerous subsequent governments rose up to replace them. The outcome of the Revolution turned France into a democratic republic, while also eliminating the role of religion from its government, making France a secular country which, to this day, remains committed to the separation of Church and State.

However, the French Revolution provides some lasting imagery of social disorder and tyrannical rule, perhaps the sort of thing we can expect to see before, during and maybe even after the End of the World.

Robespierre and the Reign of Terror

Although the French people replaced the monarchy with various political committees – all of which were supposedly equal – Maximilien de Robespierre became the face and representative of a regime which quickly became known as the Reign of Terror. The government officially embraced terror – or zero tolerance – as a means of control, with the death penalty a regular and swift judgement directed at those who stood against them. While the French people embraced the departure from the established monarchy, this new regime simply replaced poverty with oppression.

Robespierre became the focus for the people’s intense hatred and fear. There were several attempts on his life, and Robespierre personally signed a decree that allowed the execution of anyone even suspected of being an enemy of the government. As he exerted an uncomfortable amount of power over the country, Robespierre defended himself against charges of tyranny, even from within his own government.

But Robespierre ultimately fell afoul of his own fears when the military rose up against the government committees, and he was executed without trial for his part in the Reign of Terror. Before he was captured, Robespierre was shot in the face, with the bullet shattering his jaw. Differing accounts suggest this was either a failed attempted suicide or an injury received during the uprising, though it is agreed that he spent the last hours of his life in agony.

Robespierre is an interesting figure, one of the first political villains of the Modern Age and an example of what can happen when power falls into the wrong hands.

Public Execution

The term ‘capital’ punishment actually comes from the Latin word

caput

– or head – and death by decapitation is one of the most practised classical forms of execution. Capital punishment was not unique to France, but the French Revolution certainly served to reinvent the concept and turn it into something altogether different.

During the French Revolution, the government committees were keen to embrace a new form of execution that could be used for both peasants and nobility: it was necessary that all people be seen to suffer equally in the spirit of

Liberté

,

égalité

,

fraternité

.

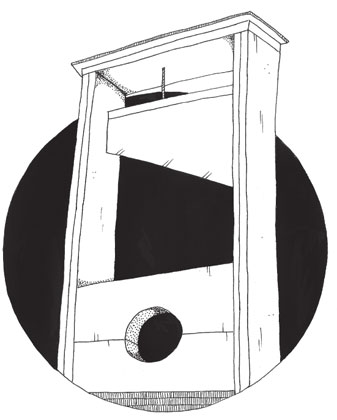

The guillotine was developed as one such method, a humane means of execution that would be both efficient and final. Other devices similar to the guillotine had been used across Europe for centuries, either strangling their victim or crushing their spine, but the guillotine perfected the art of the blade, leading to a swift, clean death.

What marks this specific form of execution as truly frightening is the spectacle that grew around these public deaths, with a morbid cult of fascination at gathering to watch each usage: programmes were sold listing the names of the condemned; parents would bring their children to warn them to behave; and, surreally, groups of knitting women would become regular features as they fought for the best seats and instigated the most vicious jeers and heckling during the execution.

There are some truly gruesome stories stemming from the usage of the guillotine including the following:

![]() Anna Maria Tussaud was a French artist who became involved in the French Revolution when her wax likenesses of the nobility were used in a protest march some days before the storming of the Bastille. She was later employed to make death masks of the deceased who had been executed. Tussaud lends her name to the well-known chain of waxwork museums, famous for their life-like sculptures.

Anna Maria Tussaud was a French artist who became involved in the French Revolution when her wax likenesses of the nobility were used in a protest march some days before the storming of the Bastille. She was later employed to make death masks of the deceased who had been executed. Tussaud lends her name to the well-known chain of waxwork museums, famous for their life-like sculptures.

![]() Charlotte Corday was executed in 1793 for the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat. After she had been beheaded, her head was seized and slapped by an onlooker. Legends tell that Corday was still alive when this happened, responding to the woman who slapped her, even though head and body had already been separated. There are several stories like this, although modern science suggests that these people were indeed dead, with any movement caused by rapidly fading brain activity.

Charlotte Corday was executed in 1793 for the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat. After she had been beheaded, her head was seized and slapped by an onlooker. Legends tell that Corday was still alive when this happened, responding to the woman who slapped her, even though head and body had already been separated. There are several stories like this, although modern science suggests that these people were indeed dead, with any movement caused by rapidly fading brain activity.

Estimates indicate that over 3,000 people were beheaded during the French Revolution, with the majority of those occurring during the Reign of Terror; the vast majority of these were personally killed by Charles-Henri Sanson, the state executioner.

The Reign of Terror remains a stark warning to any government against turning on its own people, lending much of the imagery that we see in representations of dystopian and post-Apocalyptic governments.

15

THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES

If the eighteenth century was a season for political revolution, then the nineteenth century gave us small events that made humanity more aware of our own mortality. Death and destruction became a common theme in works of art, and the increasing improvements toward education and scientific awareness meant that even the common man had an opinion on the End of the World.

One of the common themes running through nineteenth-century thought was in the departure from the religious mode of the End of the World. The groundwork was still there, and the themes remain the same, but in the wake of the Enlightenment and the revolutions of the eighteenth century, writers and philosophers began to look towards science and society for clues on the ultimate fate of humanity.

NEW ENGLAND’S DARK DAY

On 19 May 1780, inhabitants of the east coast of the United States saw an unusual sight in the sky – although they didn’t see much that day because the sky had gone completely dark. The phenomenon was witnessed as far north as Maine and extended southwards to New Jersey, leaving a complete blackness in the air that did not clear for twenty-four hours.

Some of the area’s more dramatic inhabitants thought that this was a portent for the End of the World; however, students and staff at nearby Harvard University recorded the day’s events scientifically, making observations before and after that suggested this was not the Apocalypse – but rather a large forest fire.

CHARLES DARWIN

Prior to the nineteenth century, there was no widely published system on the origin of the species; Charles Darwin’s book of that same title changed that thought significantly.

Darwin was not a religious man: although he was raised in a religious community, Darwin questioned his faith as an adult – both as a result of his scientific discoveries and the death of his daughter, an event that he found difficult to reconcile with the existence of any god.

Darwin had no specific thoughts on the End of the World, but he was amongst the first scientists and philosophers to give a legitimate theory and account of where humanity and other species on the planet had come from, in that we have common ancestors with the apes.

Darwin’s theories suggested that the concept of a divine creator was nothing more than a story, and that when the world would come to an end, it would not be as a result of these notions.

Most of Darwin’s theories have since been proven to be scientifically correct.

MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN

Although it was first published in 1818, when Darwin would have still been studying, there are many similarities in the reasoning between Darwin’s work and Mary Shelley’s Gothic horror tale.

Frankenstein

has been adapted for stage and screen many times and has become a staple of the horror genre. It is often forgotten that Frankenstein is not the name of the book’s monster – often referred to as Adam – but rather his creator, Victor Frankenstein. However, Shelley’s sympathies are with the inhuman beast, a monstrous creature spurned by a creator who is convinced that he has made an abomination against nature.

Shelley’s approach to the subject of creation is explicitly religious, with the creature taking its name from the myth of Adam and Eve: this connotation is not directly referenced in the book, but other phrases and dialogue, alongside Shelley’s writings about the book, makes this intention clear.

Shelley’s work even draws attention to the pride and hubris of Victor Frankenstein, a man who has stolen the power of creation from the gods: the novel’s subtitle of

The Modern Prometheus

calls attention to the classical tale of the Titan that stole fire from the Greek gods and gave it to humanity.

The concept of a creator that has turned his back on his creation is a recurring theme in a lot of religious texts, specifically those drawing on the Old Testament, wondering why God has forsaken his people and allowed them to suffer. If humanity has been forgotten by its God and creator, we are given a terrifying vision of what will happen to those who are forgotten by God during the End of the World.

But Shelley’s work goes further and addresses a common theme of the religious Apocalypse: the resurrection of the dead. Shelley suggests that this power no longer lies with God alone, but can be seized by humanity. But, regardless of who is responsible, this will lead to nothing but chaos and fear.

Adam’s existence is an interesting conundrum, and some scholars have drawn a line between the monster and Hobbes’

Leviathan

, with the monster standing for a society held together only by the will and creation of one individual.