The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (11 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

-Second shepherd, Second Towneley Shepherd's Play,

part of the Wakefield Cycle, c. 1450

Through climatic history, economic history, or at least agrarian

history, is reduced to being `one damn thing after another.'

-Jan de Vries

"Measuring the Impact of Climate on History, " 1981

Glacier oscillations of the last few centuries have been among

the greatest that have occurred during the last 4,000 years perhaps ... the greatest since the end of the Pleistocene ice age.

-Francois Matthes

"Report of Committee on Glaciers, " 1940

ifteen thousand years have passed since the end of the last glacial

ifteen thousand years have passed since the end of the last glacial

episode of the Great Ice Age. Since then, through the Holocene (Greek:

recent) era, the world has experienced global warming on a massive

scale-a rapid warming at first, then an equally dramatic, thousand-year

cold snap some 12,000 years ago, and since then warmer conditions, culminating in a period of somewhat higher temperatures than today, about

6,000 years before present. The past 6,000 years have seen near-modern

climatic conditions on earth.

Like the Ice Age that preceded it, the Holocene has been an endless

seesaw of short-term climate change caused by little-understood interactions between the atmosphere and the oceans. The last 6,000 years have

been no exception. In Roman times, European weather was somewhat

cooler than today, whereas the height of the Medieval Warm Period saw

long successions of warm, settled summers. Then, starting in about 1310

and continuing for five and a half centuries, the climate became more unpredictable, cooler, occasionally stormy, and subject to sporadic extremes-the Little Ice Age.

"Little Ice Age" is one of those scientific labels that came into use almost by default. A celebrated glacial geologist named Francois Matthes first used the phrase in 1939. In a survey on behalf of a Committee on

Glaciers of the American Geophysical Union, he wrote : "We are living in

an epoch of renewed but moderate glaciation-a `little ice age' that already

has lasted about 4,000 years."' Matthes used the term in a very informal

way, did not even capitalize the words and had no intention of separating

the colder centuries of recent times from a much longer cooler and wetter

period that began in about 2000 B.C., known to European climatologists

as the Sub-Atlantic. He was absolutely correct. The Little Ice Age of 1300

to about 1850 is part of a much longer sequence of short-term changes

from colder to warmer and back again, which began millennia earlier.

The harsh cold of Little Ice Age winters lives on in artistic masterpieces. Peter Breughel the Elder's Hunters in the Snow, painted during

the first great winter of the Little Ice Age in 1565, shows three hunters

and their dogs setting out from a snowbound village, while the villagers

skate on nearby ponds. Memories of this bitter winter lingered in

Breughel's mind, as we see in his 1567 painting of the three kings visiting the infant Jesus. Snow is falling. The monarchs and their entourage

trudge through the blizzard amidst a frozen landscape. In December

1676, artist Abraham Hondius painted hunters chasing a fox on the

frozen Thames in London. Only eight years later, a large fair complete

with merchants' booths, sleds, even ice boats, flourished at the same icebound location for weeks. Such carnivals were a regular London phenomenon until the mid-nineteenth century. But there was much more

to the Little Ice Age than freezing cold, and it was framed by two distinctly warmer periods.

A modern European transported to the height of the Little Ice Age

would not find the climate very different, even if winters were sometimes

colder than today and summers very warm on occasion, too. There was

never a monolithic deep freeze, rather a climatic seesaw that swung constantly backwards and forwards, in volatile and sometimes disastrous

shifts. There were arctic winters, blazing summers, serious droughts, torrential rain years, often bountiful harvests, and long periods of mild winters and warm summers. Cycles of excessive cold and unusual rainfall

could last a decade, a few years, or just a single season. The pendulum of

climate change rarely paused for more than a generation.

Scientists disagree profoundly on the dates when the Little Ice Age

first began, when it ended, and on what precise climatic phenomena are to be associated with it. Many authorities place the beginning around

1300, the end around 1850. This long chronology makes sense, for we

now know that the first glacial advances began around Greenland in the

early thirteenth century, while countries to the south were still basking

in warm summers and settled weather. The heavy rains and great

famines in 1315-16 marked the beginning of centuries of unpredictability throughout Europe. Britain and the Continent suffered

through greater storminess and more frequent shifts from extreme cold

to much warmer conditions. But we still do not know to what extent

these early fluctuations were purely local and connected with constantly

changing pressure gradients in the North Atlantic, rather than part of a

global climatic shift.

Northern Hemisphere temperature trends based on ice-core and tree-ring

records, also instrument readings after c. 1750. This is a generalized compilation

obtained from several statistically derived curves.

Other authorities restrict the term "Little Ice Age" to a period of much

cooler conditions over much of the world between the late seventeenth

and mid-nineteenth centuries. For more than two hundred years, mountain glaciers advanced far beyond their modern limits in the Alps, Iceland

and Scandinavia, Alaska, China, the southern Andes and New Zealand. Mountain snow lines descended at least 100 meters below modern levels

(compared with about 350 meters during the height of the late Ice Age

18,000 years ago). Then the glaciers began retreating in the mid- to late

nineteenth century as the world warmed up significantly, the warming

accelerated in part by the carbon dioxides pumped into the atmosphere

by large-scale forest clearance and the burgeoning Industrial Revolution-the first anthropogenic global warming.

Climate change varied not only from year to year but from place to

place. The coldest decades in northern Europe did not necessarily coincide with those in, say, Russia or the American West. For example, eastern North America had its coldest weather of the Little Ice Age in the

nineteenth century, but the western United States was warmer than in

the twentieth. In Asia, serious economic disruption, far more threatening than any contemporary disorders in Europe, occurred throughout

much of the continent during the seventeenth century. From the 1630s,

China's Ming empire faced widespread drought. The government's draconian response caused widespread revolt, and Manchu attacks from the

north increased in intensity. By the 1640s, even the fertile Yangtze River

Valley of the south suffered from serious drought, then catastrophic

floods, epidemics, and famine. Millions of people died from hunger and

the internecine wars that resulted in the fall of the Ming dynasty to the

Manchus in 1644. Hunger and malnutrition brought catastrophic epidemics that killed thousands of people throughout Japan in the early

1640s. The same severe weather conditions affected the fertile rice lands

of southern Korea. Again, epidemics killed hundreds of thousands.

Only a few short cool cycles, like the two unusually cold decades between 1590 and 1610, appear to have been synchronous on the hemispheric and global scale.

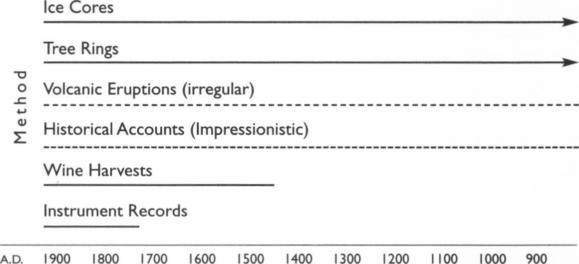

Unfortunately, scientifically recorded temperature and rainfall observations do not extend back far into history-a mere two hundred years or

less in Europe and parts of eastern North America. While these incomplete readings take us back through recent warming into the coldest part of the Little Ice Age, they tell us nothing of the unpredictable climatic

change that descended on northern Europe after 1300.

Some methods used to study the Little Ice Age

Reconstructing earlier climatic records requires meticulous detective

work, considerable ingenuity, and, increasingly, the use of statistical

methods. At best, they provide but general impressions, for, in the absence of instrument readings, statements like "the worst winter ever

recorded" mean little except in the context of the writer's lifetime and local memory. Climatic historians and meteorologists have spent many

years trying to extrapolate annual temperature and rainfall figures from

the observations of country clergymen and scientifically inclined

landowners from many parts of Europe. Extreme storms offer unusual

opportunities for climatic reconstruction. On February 27, 1791, Parson

Woodforde at Weston Longville, near Norwich in eastern England,

recorded : "A very cold, wet windy day almost as bad as any day this winter." Synoptic weather charts reconstructed from observations like Woodforde's reveal a depression that brought fierce northeasterly winds of between 70 and 75 knots along the eastern England coast for three days.

The gale brought the tides on the Thames "to such an amazing height

that in the neighborhood of Whitehall most of the cellars were underwater. The parade in St. James's Park was overflowed." Thames-side corn

fields suffered at least .£20,000 worth of damage.2