The Lord of the Rings Omnibus (1-3) (164 page)

Read The Lord of the Rings Omnibus (1-3) Online

Authors: J. R. R. Tolkien

Tags: #Fantasy - Epic, #Classics, #Middle Earth (Imaginary place), #Tolkien, #Fantasy Fiction, #Fiction - Fantasy, #General, #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Baggins, #Frodo (Fictitious character), #1892-1973, #English, #Epic, #J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel)

Long vowels were usually represented by placing the

tehta

on the ‘long carrier’, of which a common form was like an undotted

j

. But for the same purpose the

tehtar

could be doubled. This was, however, only frequently done with the curls, and sometimes with the ‘accent’. Two dots was more often used as a sign for following

y.

The West-gate inscription illustrates a mode of ‘full writing’ with the vowels represented by separate letters. All the vocalic letters used in Sindarin are shown. The use of No. 30 as a sign for vocalic

y

may be noted; also the expression of diphthongs by placing the

tehta

for following

y

above the vowel-letter. The sign for following

w

(required for the expression of

au, aw)

was in this mode the

u

-curl or a modification of it ˜. But the diphthongs were often written out in full, as in the transcription. In this mode length of vowel was usually indicated by the ‘acute accent’, called in that case

andaith

‘long mark’.

There were beside the

tehtar

already mentioned a number of others, chiefly used to abbreviate the writing, especially by expressing frequent consonant combinations without writing them out in full. Among these, a bar (or a sign like a Spanish

tilde)

placed above a consonant was often used to indicate that it was preceded by the nasal of the same series (as in

nt, mp,

or

nk);

a similar sign placed below was, however, mainly used to show that the consonant was long or doubled. A downward hook attached to the bow (as in

hobbits,

the last word on the title-page) was used to indicate a following

s,

especially in the combinations

ts

,

ps, ks (x),

that were favoured in Quenya.

There was of course no ‘mode’ for the representation of English. One adequate phonetically could be devised from the Feanorian system. The brief example on the title-page does not attempt to exhibit this. It is rather an example of what a man of Gondor might have produced, hesitating between the values of the letters familiar in his ‘mode’ and the traditional spelling of English. It may be noted that a dot below (one of the uses of which was to represent weak obscured vowels) is here employed in the representation of unstressed

and,

but is also used in

here

for silent final

e; the, of,

and

of the

are expressed by abbreviations (extended

dh,

extended

v,

and the latter with an under-stroke).

The names of the letters.

In all modes each letter and sign had a name; but these names were devised to fit or describe the phonetic uses in each particular mode. It was, however, often felt desirable, especially in describing the uses of the letters in other modes, to have a name for each letter in itself as a shape. For this purpose the Quenya ‘full names’ were commonly employed, even where they referred to uses peculiar to Quenya. Each ‘full name’ was an actual word in Quenya that contained the letter in question. Where possible it was the first sound of the word; but where the sound or the combination expressed did not occur initially it followed immediately after an initial vowel. The names of the letters in the table were (1)

tinco

metal,

parma

book,

calma

lamp,

quesse

feather; (2)

ando

gate,

umbar

fate,

anga

iron,

ungwe

spider’s web; (3)

thule (súle)

spirit,

formen

north,

harma

treasure (or

aha

rage),

hwesta

breeze; (4)

anto

mouth,

ampa

hook,

anca

jaws,

unque

a hollow; (5)

númen

west,

malta

gold,

noldo

(older

ngoldo)

one of the kindred of the Noldor,

nwalme

(older

ngwalme)

torment; (6)

ore

heart (inner mind),

vala

angelic power,

anna

gift,

vilya

air, sky (older

wilya); rómen

east,

arda

region,

lambe

tongue,

alda

tree;

silme

starlight,

silme nuquerna (s

reversed),

are

sunlight (or

esse

name),

áre nuquerna; hyarmen

south,

hwesta sindarinwa, yanta

bridge,

úre

heat. Where there are variants this is due to the names being given before certain changes affected Quenya as spoken by the Exiles. Thus No. 11 was called

harma

when it represented the spirant

ch

in all positions, but when this sound became breath

h

initially

1

(though remaining medially) the name

aha

was devised.

áre

was originally

áze,

but when this

z

became merged with 21, the sign was in Quenya used for the very frequent

ss

of that language, and the name

esse

was given to it.

hwesta sindarinwa

or ‘Grey-elven

hw’

was so called because in Quenya 12 had the sound of

hw,

and distinct signs for

chw

and

hw

were not required. The names of the letters most widely known and used were 17

n

, 33

hy,

25

r

, 10

f

:

númen, hyarmen, rómen, formen=west,

south, east, north (cf. Sindarin

dûn

or

annûn, harad, rhûn

or

amrûn, forod).

These letters commonly indicated the points W, S, E, N even in languages that used quite different terms. They were, in the West-lands, named in this order, beginning with and facing west;

hyarmen

and

formen

indeed meant left-hand region and right-hand region (the opposite to the arrangement in many Mannish languages).

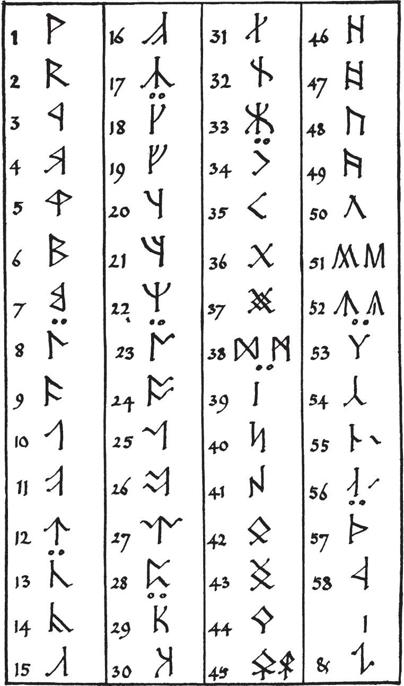

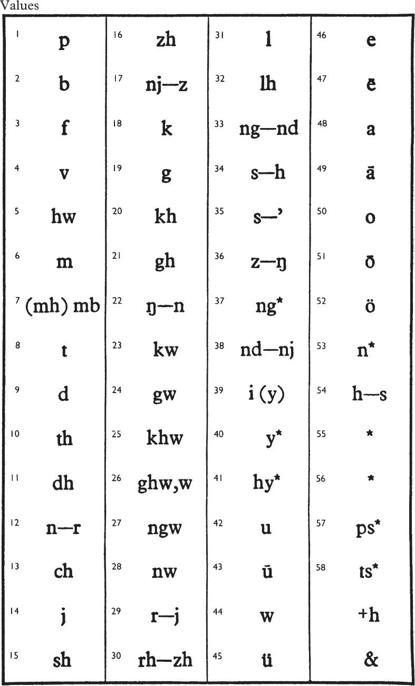

(ii)

THE CIRTH

The

Certhas Daeron

was originally devised to represent the sounds of Sindarin only. The oldest

cirth

were Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6; 8, 9, 12; 18, 19, 22; 29, 31; 35, 36; 39, 42, 46, 50; and a

certh

varying between 13 and 15. The assignment of values was unsystematic. Nos. 39, 42, 46, 50 were vowels and remained so in all later developments. Nos. 13, 15 were used for

h

or

s,

according as 35 was used for

s

or

h.

This tendency to hesitate in the assignment of values for

s

and

h

continued in later arrangements. In those characters that consisted of a ‘stem’ and a ‘branch’, 1-31, the attachment of the branch was, if on one side only, usually made on the right side. The reverse was not infrequent, but had no phonetic significance.

The extension and elaboration of this

certhas

was called in its older form the

Angerthas Daeron,

since the additions to the old

cirth

and their reorganization was attributed to Daeron. The principal additions, however, the introductions of two new series, 13-17, and 23-28, were actually most probably inventions of the Noldor of Eregion, since they were used for the representation of sounds not found in Sindarin.

THE ANGERTHAS

In the rearrangement of the

Angerthas

the following principles are observable (evidently inspired by the Fëanorian system): (1) adding a stroke to a branch added ‘voice’; (2) reversing the

certh

indicated opening to a ‘spirant’; (3) placing the branch on both sides of the stem added voice and nasality. These principles were regularly carried out, except in one point. For (archaic) Sindarin a sign for a spirant

m

(or nasal

v)

was required, and since this could best be provided by a reversal of the sign for

m,

the reversible No. 6 was given the value

m,

but No. 5 was given the value

hw.

No. 36, the theoretic value of which was

z,

was used, in spelling Sindarin or Quenya, for

ss:

cf. Fëanorian 31. No. 39 was used for either

i

or

y

(consonant); 34, 35 were used indifferently for

s;

and 38 was used for the frequent sequence

nd,

though it was not clearly related in shape to the dentals.

In the Table of Values those on the left are, when separated by--, the values of the older

Angerthas.

Those on the right are the values of the Dwarvish

Angerthas Moria.

1

The Dwarves of Moria, as can be seen, introduced a number of unsystematic changes in value, as well as certain new

cirth:

37, 40, 41, 53, 55, 56. The dislocation in values was due mainly to two causes: (1) the alteration in the values of 34, 35, 54 respectively to

h, ’

(the clear or glottal beginning of a word with an initial vowel that appeared in Khuzdul), and

s;

(2) the abandonment of the Nos. 14, 16 for which the Dwarves substituted 29, 30. The consequent use of 12 for

r

, the invention of 53 for

n

(and its confusion with 22); the use of 17 as

z,

to go with 54 in its value

s,

and the consequent use of 36 as

q

and the new

certh

37 for

ng

may also be observed. The new 55, 56 were in origin a halved form of 46, and were used for vowels like those heard in English

butter,

which were frequent in Dwarvish and in the Westron. When weak or evanescent they were often reduced to a mere stroke without a stem. This

Angerthas Moria

is represented in the tomb-inscription.

The Dwarves of Erebor used a further modification of this system, known as the mode of Erebor, and exemplified in the Book of Mazarbul. Its chief characteristics were: the use of 43 as

z;

of 17 as

ks (x);

and the invention of two new

cirth,

57, 58 for

ps

and

ts.

They also reintroduced 14, 16 for the values

j

,

zh;

but used 29, 30 for

g, gh,

or as mere variants of 19, 21. These peculiarities are not included in the table, except for the special Ereborian

cirth,

57, 58.

I

THE LANGUAGES AND PEOPLES OF THE THIRD AGE

The language represented in this history by English was the

Westron

or ‘Common Speech’ of the West-lands of Middle-earth in the Third Age. In the course of that age it had become the native language of nearly all the speaking-peoples (save the Elves) who dwelt within the bounds of the old kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor; that is along all the coasts from Umbar northward to the Bay of Forochel, and inland as far as the Misty Mountains and the Ephel Dúath. It had also spread north up the Anduin, occupying the lands west of the River and east of the mountains as far as the Gladden Fields.

At the time of the War of the Ring at the end of the age these were still its bounds as a native tongue, though large parts of Eriador were now deserted, and few Men dwelt on the shores of the Anduin between the Gladden and Rauros.

A few of the ancient Wild Men still lurked in the Drúadan Forest in Anórien; and in the hills of Dunland a remnant lingered of an old people, the former inhabitants of much of Gondor. These clung to their own languages; while in the plains of Rohan there dwelt now a Northern people, the Rohirrim, who had come into that land some five hundred years earlier. But the Westron was used as a second language of intercourse by all those who still retained a speech of their own, even by the Elves, not only in Arnor and Gondor but throughout the vales of Anduin, and eastward to the further eaves of Mirkwood. Even among the Wild Men and the Dunlendings who shunned other folk there were some that could speak it, though brokenly.

OF THE ELVES

The Elves far back in the Elder Days became divided into two main branches: the West-elves (the

Eldar

) and the East-elves. Of the latter kind were most of the Elven-folk of Mirkwood and Lórien; but their languages do not appear in this history, in which all the Elvish names and words are of

Eldarin

form.

1

Of the

Eldarin

tongues two are found in this book: the High-elven or

Quenya,

and the Grey-elven or

Sindarin.

The High-elven was an ancient tongue of Eldamar beyond the Sea, the first to be recorded in writing. It was no longer a birth-tongue, but had become, as it were, an ‘Elvenlatin’, still used for ceremony, and for high matters of lore and song, by the High Elves, who had returned in exile to Middle-earth at the end of the First Age.

The Grey-elven was in origin akin to

Quenya;

for it was the language of those Eldar who, coming to the shores of Middle-earth, had not passed over the Sea but had lingered on the coasts in the country of Beleriand. There Thingol Greycloak of Doriath was their king, and in the long twilight their tongue had changed with the changefulness of mortal lands and had become far estranged from the speech of the Eldar from beyond the Sea.

The Exiles, dwelling among the more numerous Grey-elves, had adopted the

Sindarin

for daily use; and hence it was the tongue of all those Elves and Elf-lords that appear in this history. For these were all of Eldarin race, even where the folk that they ruled were of the lesser kindreds. Noblest of all was the Lady Galadriel of the royal house of Finarfin and sister of Finrod Felagund, King of Nargothrond. In the hearts of the Exiles the yearning for the Sea was an unquiet never to be stilled; in the hearts of the Grey-elves it slumbered, but once awakened it could not be appeased.

OF MEN

The

Westron

was a Mannish speech, though enriched and softened under Elvish influence. It was in origin the language of those whom the Eldar called the

Atani

or

Edain,

‘Fathers of Men’, being especially the people of the Three Houses of the Elf-friends who came west into Beleriand in the First Age, and aided the Eldar in the War of the Great Jewels against the Dark Power of the North.

After the overthrow of the Dark Power, in which Beleriand was for the most part drowned or broken, it was granted as a reward to the Elf-friends that they also, as the Eldar, might pass west over Sea. But since the Undying Realm was forbidden to them, a great isle was set apart for them, most westerly of all mortal lands. The name of that isle was

Númenor

(Westernesse). Most of the Elf-friends, therefore, departed and dwelt in Númenor, and there they became great and powerful, mariners of renown and lords of many ships. They were fair of face and tall, and the span of their lives was thrice that of the Men of Middle-earth. These were the Númenúreans, the Kings of Men, whom the Elves called the

Dúnedain.

The

Dúnedain

alone of all races of Men knew and spoke an Elvish tongue; for their forefathers had learned the Sindarin tongue, and this they handed on to their children as a matter of lore, changing little with the passing of the years. And their men of wisdom learned also the High-elven Quenya and esteemed it above all other tongues, and in it they made names for many places of fame and reverence, and for many men of royalty and great renown.

1

But the native speech of the Númenóreans remained for the most part their ancestral Mannish tongue, the Adûnaic, and to this in the latter days of their pride their kings and lords returned, abandoning the Elven-speech, save only those few that held still to their ancient friendship with the Eldar. In the years of their power the Númenóreans had maintained many forts and havens upon the western coasts of Middle-earth for the help of their ships; and one of the chief of these was at Pelargir near the Mouths of Anduin. There Adûnaic was spoken, and mingled with many words of the languages of lesser men it became a Common Speech that spread thence along the coasts among all that had dealings with Westernesse.

After the Downfall of Númenor, Elendil led the survivors of the Elf-friends back to the North-western shores of Middle-earth. There many already dwelt who were in whole or part of Númenórean blood; but few of them remembered the Elvish speech. All told the Dúnedain were thus from the beginning far fewer in number than the lesser men among whom they dwelt and whom they ruled, being lords of long life and great power and wisdom. They used therefore the Common Speech in their dealing with other folk and in the government of their wide realms; but they enlarged the language and enriched it with many words drawn from elven-tongues.

In the days of the Númenórean kings this ennobled Westron speech spread far and wide, even among their enemies; and it became used more and more by the Dúnedain themselves, so that at the time of the War of the Ring the elven-tongue was known to only a small part of the peoples of Gondor, and spoken daily by fewer. These dwelt mostly in Minas Tirith and the townlands adjacent, and in the land of the tributary princes of Dol Amroth. Yet the names of nearly all places and persons in the realm of Gondor were of Elvish form and meaning. A few were of forgotten origin, and descended doubtless from the days before the ships of the Númenóreans sailed the Sea; among these were

Umbar

,

Arnach

and

Erech

; and the mountain-names

Eilenach

and

Rimmon

.

Forlong

was also a name of the same sort.

Most of the Men of the northern regions of the West-lands were descended from the

Edain

of the First Age, or from their close kin. Their languages were, therefore, related to the Adûnaic, and some still preserved a likeness to the Common Speech. Of this kind were the peoples of the upper vales of Anduin: the Beornings, and the Woodmen of Western Mirkwood; and further north and east the Men of the Long Lake and of Dale. From the lands between the Gladden and the Carrock came the folk that were known in Gondor as the Rohirrim, Masters of Horses. They still spoke their ancestral tongue, and gave new names in it to nearly all the places in their new country; and they called themselves the Eorlings, or the Men of the Riddermark. But the lords of that people used the Common Speech freely, and spoke it nobly after the manner of their allies in Gondor; for in Gondor whence it came the Westron kept still a more gracious and antique style.

Wholly alien was the speech of the Wild Men of Drúadan Forest. Alien, too, or only remotely akin, was the language of the Dunlendings. These were a remnant of the peoples that had dwelt in the vales of the White Mountains in ages past. The Dead Men of Dunharrow were of their kin. But in the Dark Years others had removed to the southern dales of the Misty Mountains; and thence some had passed into the empty lands as far north as the Barrow-downs. From them came the Men of Bree; but long before these had become subjects of the North Kingdom of Arnor and had taken up the Westron tongue. Only in Dunland did Men of this race hold to their old speech and manners: a secret folk, unfriendly to the Dúnedain, hating the Rohirrim.

Of their language nothing appears in this book, save the name

Forgoil

which they gave to the Rohirrim (meaning Strawheads, it is said).

Dunland

and

Dunlending

are the names that the Rohirrim gave to them, because they were swarthy and dark-haired; there is thus no connexion between the word

dunn

in these names and the Grey-elven word

Dun

‘west’.

The Hobbits of the Shire and of Bree had at this time, for probably a thousand years, adopted the Common Speech. They used it in their own manner freely and carelessly; though the more learned among them had still at their command a more formal language when occasion required.

There is no record of any language peculiar to Hobbits. In ancient days they seem always to have used the languages of Men near whom, or among whom, they lived. Thus they quickly adopted the Common Speech after they entered Eriador, and by the time of their settlement at Bree they had already begun to forget their former tongue. This was evidently a Mannish language of the upper Anduin, akin to that of the Rohirrim; though the southern Stoors appear to have adopted a language related to Dunlendish before they came north to the Shire.

1

Of these things in the time of Frodo there were still some traces left in local words and names, many of which closely resembled those found in Dale or in Rohan. Most notable were the names of days, months, and seasons; several other words of the same sort (such as

mathom

and

smial)

were also still in common use, while more were preserved in the place-names of Bree and the Shire. The personal names of the Hobbits were also peculiar and many had come down from ancient days.

Hobbit

was the name usually applied by the Shire-folk to all their kind. Men called them

Halflings

and the Elves

Periannath.

The origin of the word

hobbit

was by most forgotten. It seems, however, to have been at first a name given to the Harfoots by the Fallohides and Stoors, and to be a worn-down form of a word preserved more fully in Rohan:

holbytla

‘hole-builder’.

OF OTHER RACES

Ents.

The most ancient people surviving in the Third Age were the

Onodrim

or

Enyd. Ent

was the form of their name in the language of Rohan. They were known to the Eldar in ancient days, and to the Eldar indeed the Ents ascribed not their own language but the desire for speech. The language that they had made was unlike all others: slow, sonorous, agglomerated, repetitive, indeed long-winded; formed of a multiplicity of vowel-shades and distinctions of tone and quality which even the lore-masters of the Eldar had not attempted to represent in writing. They used it only among themselves; but they had no need to keep it secret, for no others could learn it.

Ents were, however, themselves skilled in tongues, learning them swiftly and never forgetting them. But they preferred the languages of the Eldar, and loved best the ancient High-elven tongue. The strange words and names that the Hobbits record as used by Treebeard and other Ents are thus Elvish, or fragments of Elf-speech strung together in Ent-fashion.

1

Some are Quenya: as

Taurelilómëa-tumbalemorna Tumbaletaurëa Lómëanor,

which may be rendered ‘Forestmanyshadowed-deepvalleyblack Deepvalleyforested Gloomy-land’, and by which Treebeard meant, more or less: ‘there is a black shadow in the deep dales of the forest’. Some are Sindarin: as

Fangorn

‘beard-(of)-tree’, or

Fimbrethil

‘slender-beech’.

Orcs and the Black Speech. Orc

is the form of the name that other races had for this foul people as it was in the language of Rohan. In Sindarin it was

orch.

Related, no doubt, was the word

uruk

of the Black Speech, though this was applied as a rule only to the great soldier-orcs that at this time issued from Mordor and Isengard. The lesser kinds were called, especially by the Uruk-hai,

snaga

‘slave’.

The Orcs were first bred by the Dark Power of the North in the Elder Days. It is said that they had no language of their own, but took what they could of other tongues and perverted it to their own liking; yet they made only brutal jargons, scarcely sufficient even for their own needs, unless it were for curses and abuse. And these creatures, being filled with malice, hating even their own kind, quickly developed as many barbarous dialects as there were groups or settlements of their race, so that their Orkish speech was of little use to them in intercourse between different tribes.

So it was that in the Third Age Orcs used for communication between breed and breed the Westron tongue; and many indeed of the older tribes, such as those that still lingered in the North and in the Misty Mountains, had long used the Westron as their native language, though in such a fashion as to make it hardly less unlovely than Orkish. In this jargon

tark,

‘man of Gondor’, was a debased form of

tarkil

, a Quenya word used in Westron for one of Númenorean descent; see p.

906

.